Vietnam War: Air Force Top Secret Blue Book (1962–1980)

$19.50

Description

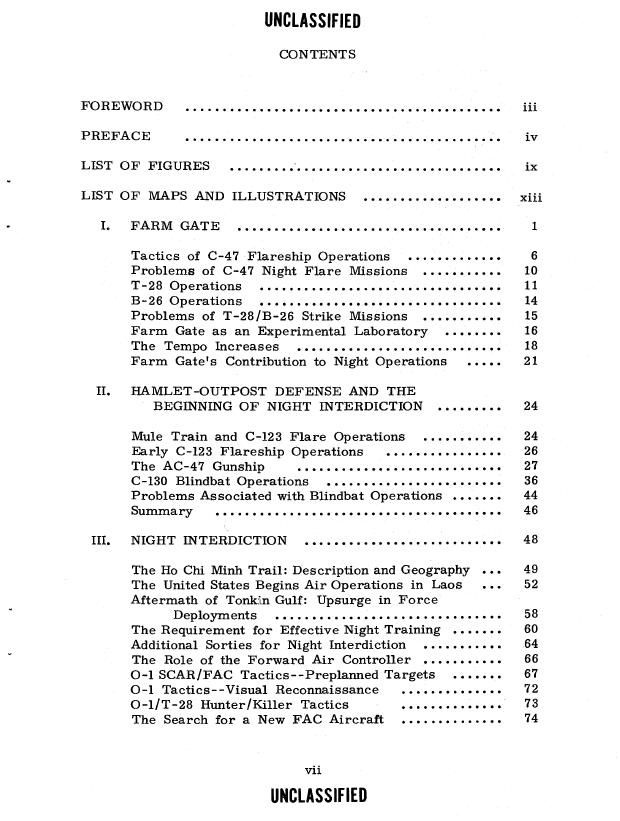

This collection comprises 4,523 pages of previously classified Air Force documents from 1962 to 1980, detailing their involvement in the Vietnam War. These historical analyses cover a broad spectrum of Air Force strategies, policies, and actions in Southeast Asia. The Air Force Historical Studies Office produced these reports, some of which remained secret until 2008.

The compilation includes 36 studies; one example is a 1968 top-secret report (declassified in 2008) on the 1966 bombing campaign against North Vietnam. This report details the political context, high-level discussions, operational limitations, and military leadership perspectives surrounding the renewed bombing. It also analyzes the decision to target North Vietnamese oil facilities, the results of those attacks, the growing strength of enemy air defenses, and ongoing assessments of the air campaign’s progress.

The report further examines specific operations: “Barrel Roll” missions (starting December 1964) targeting North Vietnamese support for the Pathet Lao; “Combat Beaver,” a joint-service plan (September-November 1966) for an electronic and ground barrier between North and South Vietnam; and “Flaming Dart,” the initial retaliatory air strikes (February 1965). Operation Gate Guard was an aerial campaign launched in May 1966 to curb North Vietnamese movement towards the DMZ, initially in northern Laos before moving to North Vietnam. Rolling Thunder, commencing in March 1965, marked the start of sustained air raids on North Vietnam. Steel Tiger, beginning in April 1965, targeted infiltration routes south of the 17th parallel in Laos. Tally-Ho, initiated in June 1966, aimed to reduce North Vietnamese troop and supply infiltration into South Vietnam through the DMZ. Tiger Hound, launched in December 1965, focused on infiltration routes in southern Laos, employing advanced air control techniques. Wild Weasel involved specialized USAF aircraft tasked with disabling North Vietnamese SA-2 missile sites. Supplementary materials detail the expansion of North Vietnamese air defenses and provide data on air sorties, aircraft losses, and anti-aircraft weaponry. A separate section covers USAF counterinsurgency strategies and capabilities from 1961-1962. In early 1961, the U.S. faced significant challenges in several global hotspots. A 1964 study, focusing on a newly critical area for the Air Force and national security, examined U.S. responses to rising global insurgencies between 1961 and 1962. This report, titled “USAF Counterinsurgency Doctrines and Capabilities,” details the development of counterinsurgency strategies and capabilities, particularly the Air Force’s contributions.

The report analyzes the U.S.’s limited counterinsurgency resources in the early 1960s, President Kennedy’s influence on the issue, the creation of Air Force counterinsurgency doctrine, inter-service disagreements, the Air Force’s relationship with U.S. Strike Command, aircraft acquisition, and the formation of specialized Air Force units.

Another study, “USAF Plans and Policies in South Vietnam, 1961-1963,” details the Air Force’s support for South Vietnam against the Viet Cong. It covers broader U.S. policy shifts towards increased military and economic aid, Air Force deployments, the Air Force’s pursuit of a larger planning role, operational aspects, Air Force-Army conflicts over air power, defoliation efforts, and support for the South Vietnamese Air Force, concluding with the 1963 Diem government coup.

Finally, a document titled “Special Air Warfare Doctrines and Capabilities, 1963” is mentioned, though its contents aren’t described. This research details the ongoing conflict between the Air Force and Army regarding special warfare roles; the Department of Defense’s approval of an Air Force plan to expand its special air warfare capabilities; the Army’s attempts to integrate aviation into its Special Forces; the connection between Strategic Command (STRICOM) and the services’ special warfare forces; the growth of special air warfare units within unified commands; the increasing significance of civic action and mobile training teams in developing countries; and advancements in acquiring more modern aircraft.

This document focuses on the Air Force’s plans and policies concerning South Vietnam and Laos in 1964. The initial sections detail the worsening military and political situation in South Vietnam following two coups, and the subsequent US responses. It highlights Air Force Chief of Staff General LeMay’s belief that only air strikes against North Vietnam could resolve the insurgencies and stabilize the South Vietnamese government. This differed from the administration’s focus on pacification and its cautious approach to avoid escalating the conflict.

The later sections briefly cover Air Force expansions, the growth of the Vietnamese Air Force, service representation issues within the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, and the impact of engagement rules on air combat training. Finally, it summarizes the early stages of Air Force special air warfare training for the Royal Laotian Air Force and the commencement of limited US air operations over Laos to counter Communist expansion. The first document examines the US Air Force’s actions in Southeast Asia in 1965, detailing how President Johnson’s decisions to bomb North Vietnam and increase military involvement in South Vietnam drastically altered their plans and operations. It emphasizes the Air Force’s role in shaping war policy, expanding military presence, and escalating air attacks.

The second document, from 1967, analyzes the Air Force’s strategic perspective on the Vietnam War, covering the Johnson administration’s deployment plans through 1968 across Southeast Asia and the Pacific. The report’s main focus is how these plans affected Air Force resources and global defense capabilities.

The third study, also from 1967, explores the Air Force leadership’s involvement in the war, including the influence of the White House, the Department of Defense, and the Joint Chiefs of Staff. It covers military expansion plans for Southeast Asia, the political implications of troop deployments, and the ongoing discussions about war strategy and air operations in North Vietnam.

The final document details the Air Force’s logistical planning and base construction in Southeast Asia during 1967. The 1968 study analyzed the Air Force’s logistical challenges in 1967 during a prolonged war. It details efforts to improve munitions supply, Southeast Asian base construction, and planning for a large-scale anti-infiltration barrier across Vietnam and Laos, demanding significant Air Force resources.

A study covering 1964-1967 explores how the Air Force expanded its personnel to handle the escalating demands of the Vietnam War. Before mid-1965, Air Force personnel numbers were declining; however, this trend reversed as the service rapidly increased its manpower.

A 1968 study assessed Air Force research and development processes, the Southeast Asia Operational Requirement system, and the Air Force’s response to North Vietnam’s improving air defenses. It also covers improvements to bombing accuracy and the major systems deployed under Project Shed Light.

A highly classified 1971 study (declassified in 2008) details the Nixon administration’s 1969 policy shifts regarding the Vietnam War, focusing on their impact on air power. President Nixon repeatedly pledged to end the Vietnam War swiftly, respecting South Vietnamese self-determination. Failing to reach a peace agreement with the Communists in Paris, he opted for a unilateral U.S. troop withdrawal, simultaneously bolstering South Vietnamese forces.

The initial U.S. troop reduction in South Vietnam, involving 25,000 soldiers, occurred in the summer of 1969.

Despite this drawdown, air power remained largely unchanged. Nixon’s strategy of “Vietnamization”—gradually withdrawing ground troops while pressuring North Vietnam—led to significantly increased reliance on the Air Force.

A 1972 top-secret report (declassified in 2008) details the planning and policy surrounding the air war in Southeast Asia during 1970, as directed by the White House, the Department of Defense, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the Air Force.

This report analyzes the Air Force’s crucial role in supporting Nixon’s decision to withdraw ground troops and instead utilize air power to aid South Vietnam. It examines early 1970 decisions to scale back air operations while simultaneously strengthening South Vietnamese forces. The report also covers internal debates on the effectiveness of air campaigns and the Air Force’s efforts to upgrade the South Vietnamese Air Force.

The 1971 period is characterized by air power providing essential support for the Vietnamization and withdrawal strategy. A 1976 Air Force document, declassified in 2008, details the service’s role in Southeast Asia during the Vietnam War withdrawal. The Air Force heavily focused on eliminating enemy resources and troops in Cambodia and Laos, assisting South Vietnamese offensives, and transferring combat responsibilities to South Vietnam. These efforts were complicated by the simultaneous withdrawal of American air units. The report contextualizes these actions within broader national policies and events of 1971. This account is a crucial and compelling piece of Air Force history.

A 1976 study, classified until 2007, chronicles the evolution of close air support tactics from 1961 to 1973. Written by Lt. Col. Ralph Rowley, it offers a pilot’s perspective on these operations, encompassing various aircraft types. The study also covers the significant contributions of Air Force gunships and the Tactical Air Control System deployed in Vietnam. A 1980 study details the U.S. Air Force’s role in the Vietnam War from 1973 to the fall of South Vietnam in late April 1975. The Air Force’s direct operations were limited to the first seven and a half months of 1973 and the final evacuation in 1975. Despite this, contingency plans for air strikes against North Vietnam remained active. Major General John W. Houston, then head of the Air Force History Office, noted that South Vietnam continued to anticipate U.S. air support even after 1973.

The book’s introduction argues that the January 1973 ceasefire and U.S. troop withdrawal didn’t end the Air Force’s story in Southeast Asia. Despite domestic pressures leading to ground troop withdrawal, the U.S. government actively sought to aid South Vietnam’s survival. This included maintaining significant air power based in Thailand. Securing the ceasefire and preventing North Vietnamese incursions was crucial for South Vietnam’s survival. The US government employed various strategies to achieve this. Maintaining B-52s in Thailand served as a deterrent, threatening a repeat of the devastating Linebacker II bombing campaign to pressure North Vietnam into respecting the peace agreement, thus giving South Vietnam time to bolster its defenses. Simultaneously, the US attempted to curb military aid from Russia and China to North Vietnam through diplomatic channels. Furthermore, ceasefires in Laos and Cambodia were sought to prevent North Vietnam from using these countries as supply routes. This diplomatic push was reinforced by continued US bombing and military support for the anti-communist governments in Laos and Cambodia. Finally, the US offered reconstruction aid to North Vietnam as an incentive to uphold the peace agreement.

The 1978 monograph details the US Air Force’s significant role during the final year of US involvement in the Vietnam War, after most ground troops had been withdrawn and North Vietnam launched its Easter Offensive. The study highlights air power’s multifaceted contribution, encompassing not only its crucial military role in repelling the offensive but also its influence on negotiations and its supportive function in US diplomacy.

The document focuses on the RF-101 Voodoo’s activities in Southeast Asia between 1961 and 1970. This paper details the RF-101 Voodoo reconnaissance aircraft’s role in the Vietnam War. Originating as the World War II-era XF-88, the McDonnell F-101 Voodoo, a supersonic, single-seat, twin-engine fighter, later evolved into the RF-101A reconnaissance variant. This version entered service in 1957, with the upgraded RF-101C following in 1959.

The RF-101C featured advanced camera systems, including oblique and vertical cameras, and a ground-view finder. Later improvements included faster cameras for low-altitude flights and enhanced controls, although smaller-format cameras were less popular. Its powerful engines provided a high speed and extensive range. Its handling characteristics made it a favorite among pilots.

RF-101C pilots played a crucial role in the Vietnam War, conducting pre- and post-strike reconnaissance missions, guiding attack aircraft, and photographing targets near the Chinese border, despite facing significant enemy opposition and suffering losses.

This 1978 report examines the B-57G’s lifecycle, from its inception to its decommissioning. Designed in 1967 under the Tropic Moon III project, the B-57G was the first jet bomber specifically equipped for independent nighttime attacks in Southeast Asia. A 1974 report details the development and use of fixed-wing gunships, drawing on interviews with key personnel and various official documents and historical analyses.

The second part of a two-part series, this study examines Air Force forward air control (FAC) operations in Southeast Asia from 1965-1970, covering the FAC force’s development, training, and aircraft (including the O-1, O-2A, OV-10, and others). It also details their tactical improvements and diverse combat roles, such as supporting ground reconnaissance and Special Forces.

This report analyzes the effects of a Department of Defense study aimed at improving contract management, summarizing the Air Force’s approach, the study’s recommendations, and the subsequent decision to centralize contract management.

This study explains the progression of command and control doctrine for close air support. A 1973 report, commissioned by the Air Staff, details the history of command and control in close air support operations.

A subsequent study examines the challenges faced by early air controllers in South Vietnam (1962-1965), including language barriers, training Vietnamese personnel, establishing centralized air control, and developing operational tactics.

Another study analyzes the logistical support of the air war in Southeast Asia between January 1968 and December 1969, highlighting problems and solutions implemented by the air logistics staff.

Additional research covers electronic countermeasures against North Vietnam, night operations (1961-1970), research and development (1965-1967), airpower deployments (1958-1963), the command and control system (1950-1966), logistics and base construction (1965-1967, 1968), limited war preparations (1958-1961), manpower trends (1960-1963), and the strengthening of Air Force laboratories and general purpose forces (1961-1964).

Air Power in the Vietnam War: Timeline of Main Events (1961-1975)

- 1961:

- January: Kennedy administration takes office, facing crises in Cuba, Congo, Laos, and Vietnam.

- Early 1961: US Air Force (USAF) begins to recognize the need for counterinsurgency capabilities, which are meager at this time.

- USAF begins developing counterinsurgency doctrine, amid debate with the Army about roles and missions.

- 1961-1962:

- USAF begins to acquire suitable aircraft and build up specially trained counterinsurgency units.

- Struggle continues between Air Force and Army over special warfare roles.

- 1961-1963:

- USAF increases support to South Vietnamese effort against Viet Cong.

- Increased military and economic assistance to South Vietnam.

- USAF deploys and augments forces in the region.

- Air Force attempts to gain a larger military planning role.

- USAF and Army disagree about the use and control of airpower in combat and training.

- Defoliation activities begin.

- USAF provides support for the Vietnamese Air Force (VNAF).

- 1962:

- Early 1962: First USAF forward air controllers (FACs) arrive in South Vietnam.

- USAF begins efforts to train VNAF personnel.

- USAF begins establishing a centralized air control system.

- Development and employment of fixed-wing gunships begins.

- 1963:

- USAF increases its special air warfare force, despite Army efforts to gain its own organic aviation.

- USAF increases civic action and mobile training teams in underdeveloped nations.

- Late 1963: Overthrow of the Diem government in Saigon.

- 1964:

- USAF Chief of Staff, Gen. Curtis E. LeMay, advocates for air strikes against North Vietnam.

- Limited USAF and Navy air operations begin in Laos to contain Communist expansion.

- The US administration adopts a “low risk” policy to avoid military escalation, due to political instability in South Vietnam.

- USAF augmentation expands and VNAF expands.

- 1965:

- April: “Steel Tiger” campaign begins in Laos.

- February: “Flaming Dart” retaliatory strikes against North Vietnam.

- March 2: “Rolling Thunder” campaign begins, initiating scheduled air strikes against North Vietnam.

- US advisory role transforms into one of active military support.

- USAF is involved in policy development for prosecuting the war.

- Build-up of US military strength in the theatre.

- Intensified air operations in South Vietnam, North Vietnam, and Laos.

- December: “Tiger Hound” begins, featuring forward air controllers and airborne command and control in Laos for some strikes.

- Forward air controller (FAC) operations grow.

- 1966:

- May 1: “Gate Guard” begins in northern Laos, then shifts to North Vietnam.

- June 20: “Tally-Ho” interdiction program starts in southern North Vietnam.

- September-November: Air Staff develops “Combat Beaver” concept for electronic and ground barrier system.

- Major air campaign against North Vietnam; restricted operations.

- USAF targets North Vietnam’s oil storage facilities.

- Enemy air defenses become more effective.

- Deployment planning impacts USAF resources and global defense.

- 1967:

- USAF logistics face major problems in preparation for a long war.

- Base construction in South East Asia expands.

- USAF works to improve its munitions situation.

- USAF begins developing new systems and equipment to counter enemy air defenses.

- The White House, the Office of the Secretary of Defense, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the recommendations of the Military Assistance Command Vietnam (MACV) are reviewed.

- Plans for the military buildup in Southeast Asia are developed.

- Political considerations are associated with new force deployments.

- Debate over war strategy continues.

- B-57G “Tropic Moon III” program begins.

- 1968:

- Investigations of USAF research and development procedures begin.

- Review of Southeast Asia Operational Requirement system.

- 1968-1969:

- Logistics plans are developed and problems are addressed by air logistics staff.

- 1969:

- Nixon administration introduces policy changes affecting air power in the Vietnam war.

- President Nixon begins withdrawing US forces while strengthening Saigon’s forces.

- First reduction of 25,000 troops in South Vietnam occurs.

- Airpower is not materially reduced, instead, greater use of air power to maintain pressure on North Vietnam to negotiate.

- 1970:

- Washington-level decisions in early 1970 reduce air operations while steps to strengthen Saigon’s forces are taken.

- Debates about the effectiveness of the various air campaigns continue.

- USAF works to improve and modernize the VNAF.

- 1971:

- Massive USAF efforts target enemy stockpiles and troop concentrations in Cambodia and Laos.

- USAF supports South Vietnamese ground attacks in the Laotian panhandle.

- USAF attempts to Vietnamize the interdiction function.

- USAF works to counter enemy air buildup in late 1971.

- Some US air units are withdrawn as part of the overall drawdown.

- 1972:

- Air power plays a critical role in turning back the North’s Easter offensive.

- Airpower influences negotiations and US diplomacy.

- 1973:

- January: Cease-fire agreement is signed and all US forces withdrawn.

- USAF operational involvement spans the first seven and a half months of the year.

- Plans for retaliatory air attacks against North Vietnam remain in effect.

- US administration continues efforts to increase South Vietnam’s chances of survival.

- B-57G “Tropic Moon III” program ends.

- 1975:

- USAF involved in evacuation efforts, during the defeat of South Vietnam.

Cast of Characters

- President John F. Kennedy: President of the United States (1961-1963). His administration faced crises in multiple locations, including Vietnam, and sought to develop counterinsurgency strategies.

- General Curtis E. LeMay: USAF Chief of Staff. He advocated for air strikes against North Vietnam to end the insurgencies in South Vietnam and Laos.

- President Lyndon B. Johnson: President of the United States (1963-1969). He made the key decisions to bomb North Vietnam and transform the US advisory role into active military support.

- President Richard Nixon: President of the United States (1969-1974). He implemented the policy of “Vietnamization,” emphasizing the withdrawal of US troops and the strengthening of South Vietnamese forces, and increasingly relied on air power.

- Lt. Col. Ralph Rowley: Author of the study “Tactics and Techniques of Close Air Support Operations 1961 – 1973.”

- Major General John W. Houston: Chief of the Office of Air Force History.

- E.H. Hartsook: Wrote the introduction to “End of US Involvement, 1973-1975.”

Related products

-

Civil War: Battle of Antietam (Sharpsburg) – National Park Service Archives

$9.99 Add to Cart -

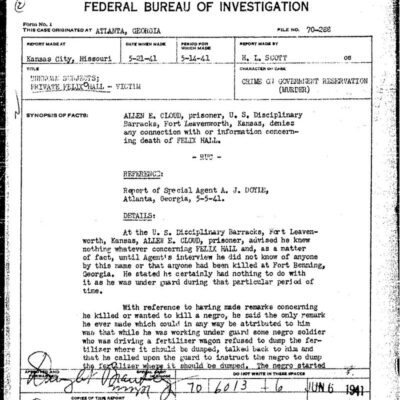

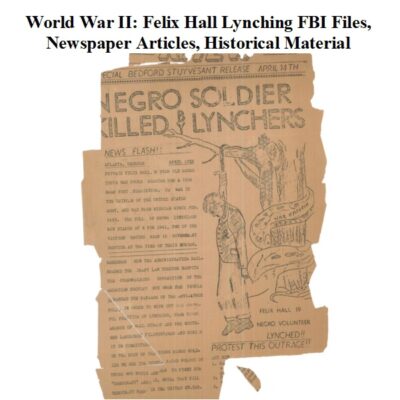

World War II: Felix Hall Lynching – FBI Files, Articles, Historical Records

$9.99 Add to Cart -

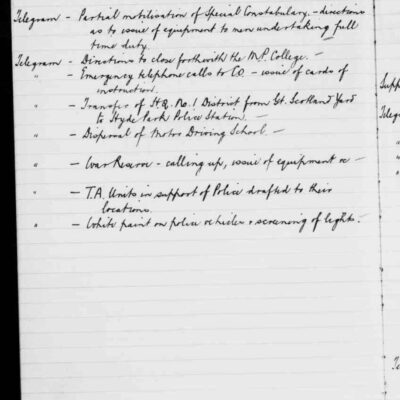

World War II: Scotland Yard War Diary from 1939 to 1945

$3.94 Add to Cart -

Korean War: CIA Covert Operations History – The Secret Conflict in Korea

$3.94 Add to Cart