The Revolution Susan B Anthony Suffrage/Women’s Rights

$19.50

Description

Susan B. Anthony’s Suffrage/Women’s Rights Newspaper: The Revolution

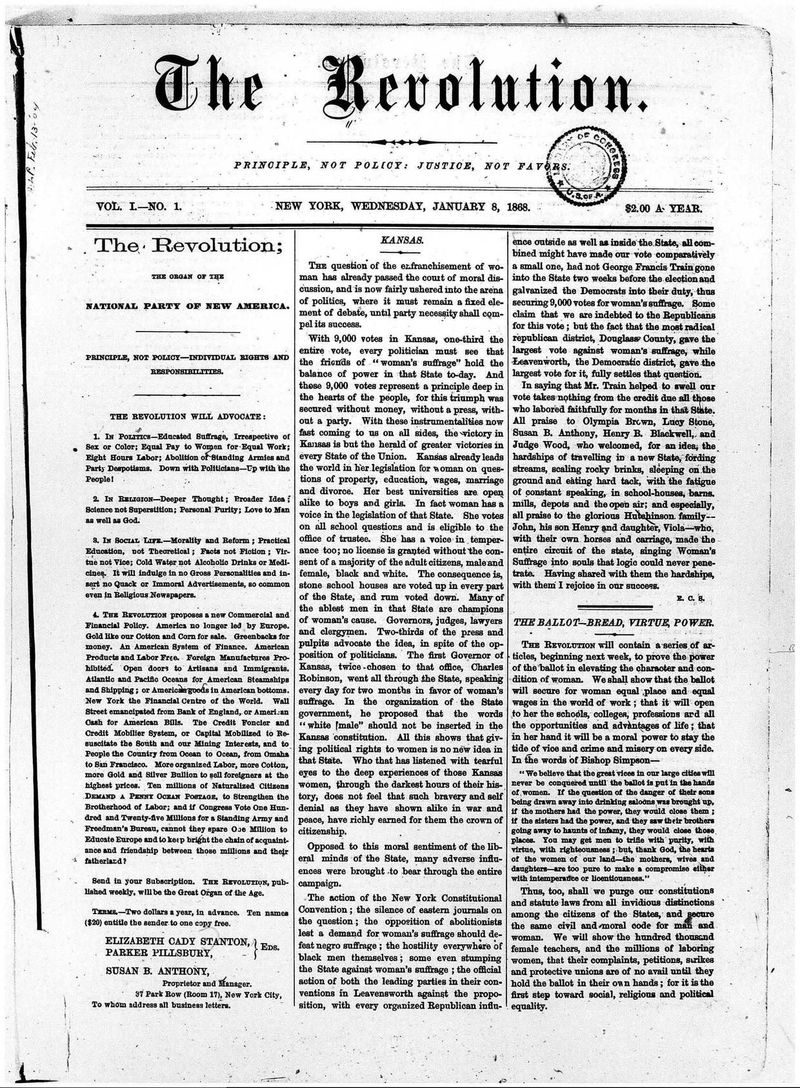

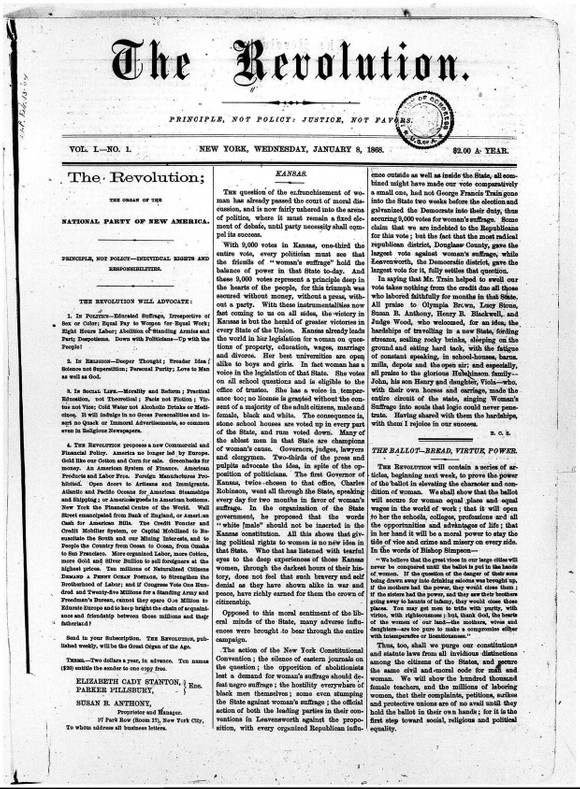

The Revolution was a women’s rights weekly newspaper established by Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, comprising 3,408 pages from its inaugural issue on January 8, 1868, to its final edition on February 17, 1872.

Cheris Kramarae and Lana F. Rakow, authors of The Revolution in Words, Righting Women, 1868-1871, have characterized The Revolution as one of the most significant documentary resources for understanding women’s history in the nineteenth century. Contemporary readers of the publication gain insight into the concerns, grievances, solutions, principles, and philosophies that occupied the minds of many women during that time, conveyed directly through their words.

Founded in New York City by women’s rights advocates Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, the first issue was released on January 8, 1868. Anthony managed the newspaper’s business operations, while Stanton and co-editor Parker Pillsbury, a prominent male feminist of the era, oversaw its editorial content. The initial funding for the newspaper came from the controversial businessman George Francis Train, whose eccentricities troubled many suffragists affiliated with the Republican Party. During the Civil War, Train delivered speeches that opposed secession but supported slavery, earning him the label “copperhead,” a term used for Northern Democrats who sympathized with the Confederacy.

Anthony and Stanton met in 1851, leading to a lifelong friendship and collaboration on social reform initiatives. In 1852, they established the New York Women’s State Temperance Society after Anthony was denied the chance to speak at a temperance conference due to her gender. In 1863, they formed the Women’s Loyal National League, which organized the largest petition campaign in U.S. history up to that point, gathering nearly 400,000 signatures advocating for the abolition of slavery. In 1866, they launched the American Equal Rights Association, aimed at ensuring equal rights for all American citizens, particularly the right to vote, regardless of race, color, or gender.

The publication of The Revolution began in 1868, and when disagreements over ideology and strategies divided the women’s movement, they founded the National Woman Suffrage Association in 1869.Prior to the Revolution, the two leading newspapers focused on women’s rights were The Lily, established by Amelia Jenks Bloomer and published from 1849 to 1851, and The Una: A Paper Devoted to the Elevation of Woman, founded by Paulina Wright Davis and in circulation from 1853 to 1855. In January 1870, Lucy Stone launched a competing publication called The Woman’s Journal. Among these publications, The Revolution was regarded as the most radical of its era.

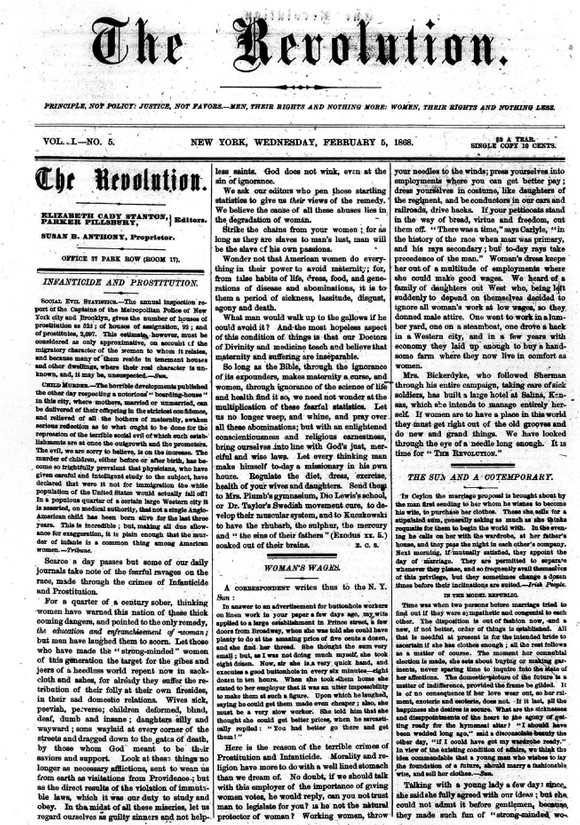

The inaugural issue, released on January 8, 1868, featured the slogan “Principle, not Policy: Justice, Not Favor” prominently displayed beneath its title. By the second issue, the motto was expanded to include “Men their Rights and Nothing More, Women their Rights and Nothing Less.” The newspaper boldly pushed for the acknowledgment of fundamental rights and freedoms that women were denied, employing an assertive tone consistent with its name. It addressed not only women’s suffrage but also various social issues, politics, labor movements, and financial matters. The paper tackled topics that were considered taboo in other publications, such as domestic violence, divorce, rape, prostitution, and reproductive rights.

In its mission statement, The Revolution proclaimed its commitment to advocating for: IN POLITICS—Educated Suffrage, Regardless of Sex or Color; Equal Pay for Women for Equal Work; Eight-Hour Workdays; the Abolition of Standing Armies and Party Tyrannies. Down with Politicians—Up with the People!

The newspaper included coverage of news and events relevant to its focus; shared the activities and viewpoints of its founders, editors, and contributors; featured letters and submissions from readers and others involved in the women’s movement; reported on the establishment and activities of the National Woman Suffrage Association; presented a financial section discussing monetary and trade policies; provided foreign correspondence detailing the status and advancements of women globally; showcased poetry and fiction; announced events; and published transcripts of speeches, conference proceedings, and testimonies before governmental bodies.

One of the notable achievements of the publication was its ability to bring women’s rights and suffrage back into public discourse after these topics had lost prominence during the Civil War. The paper highlighted the pivotal roles of Anthony and Stanton in the suffrage movement during the latter part of the 19th century. The efforts involved in creating and distributing The Revolution contributed to the establishment of the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA). In 1890, the NWSA joined forces with the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA) to create the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). The Revolution successfully engaged more working-class women in the women’s movement by addressing issues related to unionization and discrimination against female workers.

In 1868, the publication launched a campaign advocating for Hester Vaughn, a domestic worker who became pregnant by her former employer. After the child died shortly after birth, Vaughn was accused and convicted of negligence leading to the baby’s death. An editorial in The Revolution portrayed Vaughn as a poor, uneducated, isolated young woman who had killed her newborn out of desperation, stating that if she were executed, it would be an act of murder far worse than the death of her child.

As the campaign for Vaughn progressed, The Revolution presented alternative facts, suggesting that the infant’s death was either natural or accidental: “During one of last winter’s worst storms, she was without food, warmth, or proper clothing. She had been ill and partly unconscious for three days before giving birth, and hours passed before she could reach the door to call for help, only to be taken to prison.” Following the publicity surrounding the case, Stanton met with Pennsylvania Governor John W. Geary, who granted Vaughn a pardon.

Shortly thereafter, she was deported back to England.Numerous social reformers were profoundly troubled by The Revolution’s refusal to endorse the proposed Fifteenth Amendment, which aimed to grant voting rights to black men, unless it was paired with another amendment that would also grant suffrage to women. As the Fifteenth Amendment progressed through Congress, Stanton’s stance caused a significant divide within the women’s rights movement itself. Many prominent figures in this movement, such as Lucy Stone, Elizabeth Blackwell, and Julia Ward Howe, strongly opposed Stanton’s all-or-nothing approach. Coming from a wealthy and socially influential background, Stanton expressed her views in The Revolution using language that sometimes appeared elitist and racially dismissive. She wrote, “American women of wealth, education, virtue, and refinement, if you do not want the lower classes of Chinese, Africans, Germans, and Irish, with their inferior notions of womanhood, to legislate for you and your daughters… demand that women be represented in government as well.”

By 1869, the disagreement over the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment led to the formation of two distinct women’s suffrage organizations. The National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) was established by Anthony and Stanton. The NWSA opposed the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment without amendments to include women’s suffrage and, particularly under Stanton’s influence, advocated for several women’s issues that were considered too radical by more conservative members of the suffrage movement. In 1870, the Fifteenth Amendment was enacted with its original wording: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

At this point, the newspaper began experiencing significant financial difficulties. George Francis Train contributed $3,000, while his business partner added $7,000 towards the establishment of the newspaper. However, Train’s financial support ended shortly after the publication of the first issue. In early 1868, Train traveled to England, where he was arrested and imprisoned for advocating for Irish independence. Anthony resisted increasing the subscription price for the paper and declined to accept lucrative advertising for dubious medical products that often contained alcohol and morphine.By May 1870, The Revolution was facing significant financial difficulties. Anthony took on $10,000 of the debt and sold the publication for just $1 to affluent women’s rights advocate Laura Curtis Bullard. Over the next six years, a substantial portion of Anthony’s income from speaking engagements went towards settling this debt.

Under Bullard’s leadership, the paper adopted a more conservative stance and approached women’s issues in a less radical manner. She introduced a new motto for The Revolution: “What therefore God hath joined together, let not man put asunder.” Stanton and a few others who had previously contributed to the publication occasionally wrote for it during Bullard’s tenure.

Bullard sought to boost revenue by increasing the number of advertisements, including those for patent medicines, which Anthony refused to accept, many of which were produced by Bullard’s own family business. In October 1871, Bullard stepped down from her role at the newspaper.

On October 28, 1871, control of the newspaper was handed over to Reverend W. T. Clarke and publisher J. N. Hallock. They established a new motto: “Devoted to the Interest of Woman and Home Culture.” Although Clarke supported women’s suffrage, he adopted a different perspective compared to earlier editors of The Revolution. In his inaugural issue, he stated, “Most men are exceedingly kind to women and treat them with too much tenderness rather than too little. More women among us are harmed by indulgence rather than injustice.”

Four months later, The Revolution published its final issue on February 17, 1872. Nearly fifty years later, the Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution was ratified, declaring, “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.”

Front page of the first issue of The Revolution, January 8, 1868

The Revolution, February 5, 1868

Highlights include:

The Revolution, July 9, 1868, Pages 8 and 9.

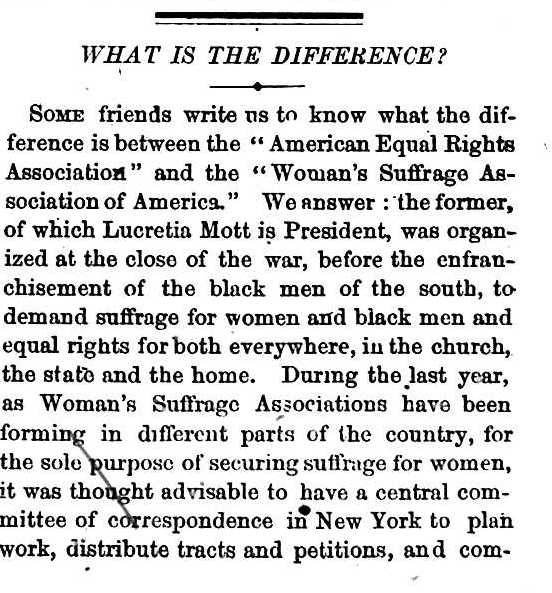

In May 1868, The Revolution announced the establishment of the Woman’s Suffrage Association of America, which was intended to act as a coordinating body for local women’s suffrage groups that had emerged across the nation. Its leadership included Stanton and Anthony, and it operated from the same office as The Revolution. Stanton later remarked that The Revolution, advocating for universal suffrage regardless of race or gender, specifically represented the Woman’s Suffrage Association of America.

The Revolution expressed support for the National Labor Union (NLU), and both Anthony and Stanton aimed to collaborate with it to forge a broad coalition that could lead to the creation of a new political party advocating for women’s suffrage alongside the rights of workers. The Revolution stated, “The principles of the National Labor Union are our principles,” and predicted that “the producers, the working men, the women, and the African Americans” would unite to seize control of the government from non-producers, land monopolists, bondholders, and politicians. Although the NLU responded positively to The Revolution’s outreach, the expected partnership did not materialize.

Following the Civil War, many major publications linked to radical social reform movements either became more conservative or ceased operations. Anthony envisioned The Revolution as a means to help fill this gap, aspiring to eventually develop it into a daily newspaper run entirely by women, complete with its own printing press.

The Woman’s Suffrage Association of America published a petition in The Revolution advocating for women’s suffrage and encouraged readers to help circulate it.Numerous social reformers were greatly troubled by The Revolution’s refusal to endorse the proposed Fifteenth Amendment, which aimed to grant voting rights to black men, unless it was paired with another amendment that would also grant suffrage to women. Stanton, who hailed from a wealthy and socially influential background, opposed this in The Revolution using language that at times appeared elitist and racially patronizing. She stated that American women of wealth, education, virtue, and refinement should demand representation in government to prevent those of lower social standing, such as Chinese, Africans, Germans, and Irish, with their inferior views on womanhood, from making laws for them and their daughters.

The publication actively engaged in debates with its critics. When the New York World questioned why women did not remain passive in their conventions and allow prominent men to speak on their behalf, Elizabeth Cady Stanton retorted that they could similarly ask the editorial team of The World why they did not stop writing and let distinguished men take over the editing of their publication.

Bullard introduced a new motto for the paper, a Biblical phrase: “What therefore God hath joined together, let not man put asunder,” commonly used in marriage ceremonies. One historian speculated that Bullard chose this motto partly to counter claims that the women’s rights movement threatened the institution of marriage. However, she provided her own interpretation, asserting that it represented not just one specific idea but many noble concepts. She argued that women have been systematically separated from men throughout history and are now entitled to assert and uphold their marital rights. Women should have equal opportunities alongside men in various fields, including trades, education, public speaking, journalism, literature, science, art, and governance.

Related products

-

Journal of the Congress of the Confederate States of America 1861-1865

$19.50 Add to Cart -

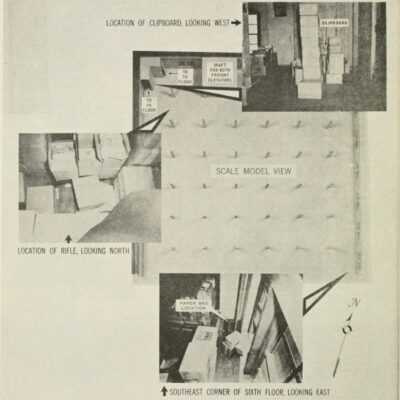

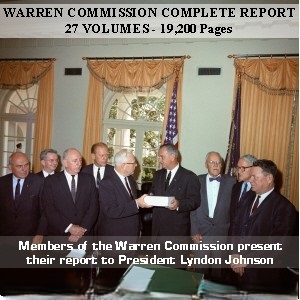

Warren Commission Report: 27 volumes, 19,200 pages

$19.50 Add to Cart -

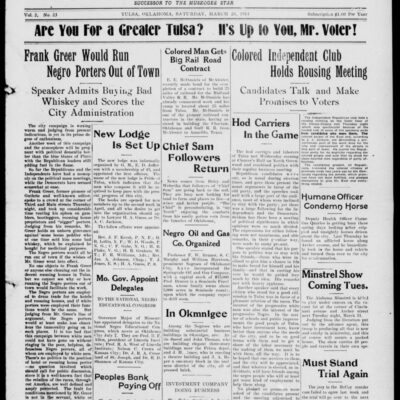

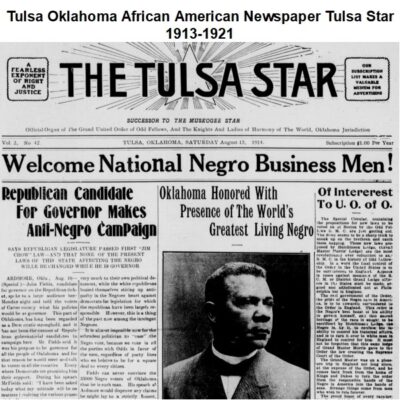

Tulsa Oklahoma African American Newspaper Tulsa Star 1913-1921

$9.90 Add to Cart -

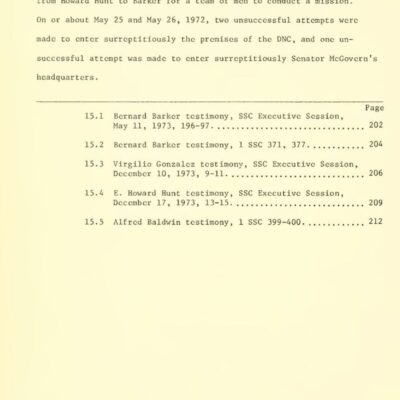

Watergate: Congressional hearings, reports, exhibits, and transcripts

$19.50 Add to Cart