Slavery Political Cartoons: Cartoon Slavery 1789 – 1880

$19.50

Description

Beyond the 174 illustrated works detailed below, this collection boasts three additional digitized volumes focusing on Civil War imagery. These include “Ye Book of Copperheads,” a 34-page publication from 1863; “American Caricatures Pertaining to the Civil War,” a more substantial 180-page work from 1918; and excerpts from “Sketches from the Civil War in North America, 1861, ’62, ’63,” a 1917 compilation featuring clandestine Confederate illustrations.

Political Cartoons on Slavery

The main collection, housed within the Library of Congress, comprises 174 illustrations that serve as a visual record of political commentary from the period. This rich archive encompasses satirical drawings, caricatures, and allegorical representations, primarily reflecting American civic life and governance. The majority of these prints were individually published, with a significant concentration dating between 1840 and 1864, particularly highlighting the presidential election years of 1848, 1852, 1856, 1860, and 1864. A smaller subset of the illustrations originates from books and periodicals of the era.

Each image within the digital collection is accompanied by a descriptive page, resulting in approximately 200 pages of supplementary information. Images with intricate political themes or obscure allusions receive more detailed explanations, examples of which are provided below.

The core subject matter revolves around slavery and pivotal events and personalities within the mid-19th-century abolitionist and anti-abolitionist movements. The collection also includes post-Civil War pieces addressing Reconstruction and the post-slavery South. The pervasive presence of slavery underscores the political context of each illustration.

These primary source materials offer invaluable insights into the prevailing attitudes, viewpoints, sensitivities, and beliefs of the time. It’s important to note that many of these images contain racial stereotypes and offensive language. Although such terms may be omitted from the concise descriptions provided here, the digital images and their full descriptions remain uncensored to maintain historical accuracy. Nineteenth-century political cartoons frequently employed a distinctive visual approach: they blended various contemporary issues into a single image. This technique wasn’t simply about depicting multiple subjects; it was about weaving them together to reflect the prevailing political climate and the challenges faced by the people depicted. The cartoons didn’t just show individual problems in isolation; instead, they created a visual tapestry where social, economic, and political concerns were intricately interwoven.

This composite style allowed cartoonists to offer a nuanced and multifaceted commentary on the era’s complexities, showing how different aspects of life were interconnected and influenced one another. The individuals portrayed weren’t simply stand-ins for specific people, but rather represented broader societal groups grappling with the prevailing issues of the day. The resulting image was a powerful synthesis, offering a richer and more insightful perspective than a series of individual, unconnected depictions could achieve. Essentially, the cartoon became a microcosm of the era’s political and social realities. This 1848 caricature, titled “Studying Political Economy,” cleverly satirizes Zachary Taylor’s presidential candidacy, highlighting his military background and perceived lack of political acumen. The drawing depicts Taylor, a student in this allegorical scene, seated humbly before his more experienced running mate, Millard Fillmore. His makeshift crown fashioned from “The True Whig” newspaper underscores his superficial connection to the Whig party. He struggles with a book titled “Congressional Debates 1848. Slavery…”, laboriously sounding out the words “Wilmot Proviso,” revealing his unfamiliarity with complex political issues. His boastful declaration, “What do I know about such political stuff. Ah! Wait until I get loose, Then you will see what fighting is!” showcases his confidence in military prowess over political understanding. A discarded “National Bank” document at his feet further emphasizes his lack of engagement with economic policy.

Fillmore, in contrast, is shown studying “The Glorious Whig Principles [by] Henry Clay,” representing his adherence to established Whig ideology. He chides Taylor, urging him to abandon his aggressive approach, emphasizing the party’s purported peacefulness and righteousness. The juxtaposition of Fillmore’s scholarly setting – a cabinet containing the Constitution and a globe – with the items behind Taylor – maps of “The Late War” and a biography of the controversial John Tyler – visually reinforces the contrast between their political experience and approaches.

The inclusion of a bloodhound wearing a “Florida” collar at Taylor’s feet serves as a pointed reminder of the controversial tactics employed during his involvement in the Second Seminole War. Two young Black men polishing Taylor’s weapons add another layer of commentary, their dialogue – “By golly! Massa Taylor like fighting better then him dinner” and “Dis am de knife wot massa use to cut up de Mexijins wid” – highlighting the brutal realities of Taylor’s military career and potentially hinting at the racial implications of his actions. Finally, the toy soldiers and cannons scattered on the floor symbolize the simplistic, almost childish, view of politics held by Taylor, contrasted with the complexities of governance represented by Fillmore’s surroundings. The entire piece is a masterful use of visual metaphor to critique Taylor’s suitability for the presidency. This single illustration is a remarkably comprehensive visual commentary on the tumultuous period of American history leading up to the Civil War. It doesn’t simply depict a single event, but rather tackles a vast array of interconnected political, social, and economic issues that defined the era. The artist uses the visual medium to address the complex debate surrounding the Wilmot Proviso, a proposed amendment that aimed to prohibit slavery in any territory acquired from Mexico after the Mexican-American War. This single piece of artwork cleverly weaves together the controversies surrounding this amendment with the broader context of the era.

The artwork features a multitude of prominent figures from the time, ranging from presidents like Zachary Taylor and Millard Fillmore to key political players such as John C. Calhoun and Henry Clay, as well as abolitionist leaders like William Lloyd Garrison and Frederick Douglass. The inclusion of figures like Abraham Lincoln and Jefferson Davis foreshadows the impending conflict. Even military leaders such as Ulysses S. Grant and Winfield Scott are depicted, highlighting the military dimension of the era’s tensions. The presence of figures like Dred Scott underscores the legal battles over slavery. In essence, the illustration presents a veritable “who’s who” of the antebellum period.

The subjects addressed are equally diverse and interconnected. The illustration tackles the moral and ethical dilemmas surrounding slavery, including the brutal realities of the slave trade, as evidenced by the title of one specific illustration within the larger work. It explores the various political movements of the time, from the abolitionist movement and the Liberty Party to the Whig Party and the Nativist movement. Economic issues, such as the U.S. banking system, are also represented, showing the artist’s understanding of the complex interplay between political and economic forces. Further, the illustration covers significant events such as the Compromise of 1850, the Fugitive Slave Act, “Bleeding Kansas,” and the lead-up to the Civil War, including the 1860 Democratic Convention.

The artist even touches upon the international relations of the time, referencing Great Britain and the Ostend Manifesto. The illustration also incorporates social movements like the temperance movement and the fight for women’s suffrage, demonstrating the artist’s awareness of the broad spectrum of social reform efforts underway. In short, the artwork serves as a powerful visual synthesis of the complex and multifaceted issues that shaped 19th-century America. This 1792 British etching, attributed to the renowned caricaturist Isaac Cruikshank, depicts a horrifying scene aboard a slave ship. The image shows a young African girl cruelly suspended by her ankle from a rope and pulley system. A sailor is shown carrying out this act of brutality. Standing nearby, whip in hand, is Captain John Kimber, the master of the vessel, who became infamous within the burgeoning British abolitionist movement.

This illustration serves as a visual representation of the accusations leveled against Captain Kimber. In 1791, while commanding the slave ship Recovery, he was charged with the murder of this same girl. The testimony presented at his trial revealed a grim account: the ship’s surgeon and third mate claimed the girl perished as a direct result of Captain Kimber’s brutal punishment. Specifically, they testified that Kimber had her hoisted by her ankle and then flogged her for refusing to eat.

Despite this damning evidence, a High Court of Admiralty jury surprisingly acquitted Captain Kimber. However, the court found the ship’s surgeon and third mate guilty of perjury for their testimony against him, a decision that further fueled the outrage of abolitionists. The etching, therefore, not only documents a specific instance of alleged cruelty but also underscores the challenges abolitionists faced in bringing perpetrators of such crimes to justice within a legal system seemingly biased in favor of those involved in the transatlantic slave trade. The contrast between the visual horror of the etching and the judicial outcome highlights the deep-seated injustices of the era. The work’s inclusion of Captain Kimber, a figure already notorious amongst abolitionists, suggests an intentional attempt to use the powerful medium of visual art to sway public opinion against the slave trade. The 1841 illustration presents a romanticized, unrealistic view of slavery in America, deliberately obscuring the brutal realities experienced by enslaved Black people. According to Frank Weitenkampf, a former curator at the New York Public Library, such images were likely produced and disseminated by pro-slavery advocates in the North, aiming to justify the institution.

One such advocate, E. W. Clay, consistently demonstrated a lack of empathy towards the enslaved population in his work. This particular illustration depicts a prosperous white family – a father, mother, and their two children – presented as idyllic and affluent. The scene is further embellished with a graceful greyhound, adding to the air of comfortable wealth. Their son points towards an elderly Black couple and their child, who are depicted humbly seated. In the background, a group of enslaved people are shown engaging in what appears to be joyful dancing. The elderly Black man’s words, “God Bless you massa! you feed and clothe us. When we are sick you nurse us, and when too old to work, you provide for us!” are a clear attempt to portray the master as benevolent and the enslaved as content. The master’s pious declaration, “These poor creatures are a sacred legacy from my ancestors and while a dollar is left me, nothing shall be spared to increase their comfort and happiness,” further reinforces this fabricated narrative of paternalistic care. The image, therefore, serves as blatant propaganda, masking the horrific violence, dehumanization, and exploitation inherent in the system of slavery. The title, “Effects of the Fugitive-Slave-Law,” is ironic, as the illustration completely ignores the harsh realities that the law imposed on enslaved people who attempted to escape their bondage.

The image is a carefully constructed fabrication designed to deflect criticism and maintain the status quo of slavery. This 1850 lithograph serves as a powerful visual indictment of the Fugitive Slave Act, a piece of legislation passed by Congress that significantly intensified the federal government’s and free states’ roles in capturing runaway slaves. The act’s provisions included the authorization of federal commissioners to issue arrest warrants for suspected fugitives, and it further empowered these officials to command the assistance of posses and even ordinary citizens in apprehending escapees. The artwork depicts a harrowing scene: four Black men, likely freedmen, are ambushed in a cornfield by a posse of six armed white men. The violence is starkly portrayed; one white man fires his weapon, two others reload, and two of the Black men are shown wounded, one fallen and the other reeling from a head wound. The remaining two Black men watch in terror.

The image’s impact is amplified by the inclusion of two contrasting textual excerpts placed beneath the illustration. One quote, from Deuteronomy, advocates for the protection of runaway slaves, prohibiting their return to their owners and guaranteeing them the right to choose their place of residence. The second quote, from the Declaration of Independence, asserts the fundamental equality of all men and their inherent rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. This juxtaposition highlights the stark contradiction between the biblical principle of sanctuary and the brutal reality enforced by the Fugitive Slave Act.

The lithograph itself is noteworthy for its artistic merit, exceeding the typical quality of political prints from that era. The artist displays exceptional skill in both the lithographic technique and the rendering of the figures, resulting in a compelling and emotionally resonant image. The precision and detail in the depiction of the figures’ expressions and postures further enhance the scene’s emotional power, effectively conveying the horror and injustice of the situation. The piece’s artistic excellence elevates its message, making it a particularly effective tool for conveying the moral outrage against the Fugitive Slave Act. The 1844 lithograph, “Anti-Annexation Procession,” satirizes the opposition to the United States’ annexation of Texas during the presidential campaign that year. The image depicts a bizarre parade led by Whig candidate Henry Clay, a declared opponent of annexation, comically astride an animal resembling a fox, rather than a raccoon. This immediately establishes a tone of ridicule and undermines Clay’s serious stance.

Following Clay are three distinct factions, each representing a different group opposed to annexation, and each portrayed in a mocking and exaggerated manner. The first group, positioned on the right, are identified as “Hartford Convention Blue-Lights,” a reference to Federalists who opposed the War of 1812. Their cries of “God save the King!” and “Millions for Tribute! not a cent for defence Go it Strong!” highlight their perceived disloyalty and prioritize financial interests over national defense, further discrediting their anti-annexation position.

Next, in the center, is a procession of “Sunday Mail Petitioners,” headed by Clay’s running mate, Theodore Frelinghuysen, depicted riding a donkey in clerical garb. This group advocated for the cessation of mail delivery on Sundays, a stance interpreted by many as an overreach of religious influence into government, thus threatening the separation of church and state. The statement, “I go for the Good old times! wholesome, Fine and Imprisonment!” mocks their perceived desire for a stricter, more puritanical society.

Finally, on the far left, is the prominent abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison leading a group of “Abolition Martyrs,” who have been subjected to tarring and feathering for their activism. Garrison’s banner, proclaiming “Non Resistance, No Government No Laws–Except the 15 Gallon Law!” (likely a satirical reference to liquor laws), serves as a humorous yet pointed critique of the perceived radicalism of some abolitionists, suggesting their views were impractical and extreme.

In essence, the lithograph uses caricature and satire to portray the diverse and arguably disparate groups opposing the annexation of Texas as a disorganized and somewhat ridiculous collection of individuals, thereby subtly undermining their arguments against annexation. The artist cleverly uses visual humor to sway public opinion in favor of annexation by associating the opposition with unpopular and extreme viewpoints. This 1850 caricature playfully depicts a dramatic moment from the intense Senate debate concerning California’s admission as a free state. The illustration captures the incident where Senator Henry S. Foote of Mississippi brandished a pistol at Senator Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri. The image shows Benton, positioned centrally, dramatically flinging open his coat, boldly proclaiming his willingness to face Foote’s threat. His defiant words, “Get out of the way, and let the assassin fire! let the scoundrel use his weapon! I have no arm’s! I did not come here to assassinate!” are clearly intended to portray Benton as the wronged party. He is flanked by Willie P. Mangum of North Carolina to his left, suggesting support or perhaps a protective presence.

Foote, meanwhile, is physically restrained by Andrew Pickens Butler of South Carolina, while Daniel Stevens Dickinson of New York attempts to de-escalate the situation, eventually receiving the pistol from Foote. Despite being held back, Foote maintains a threatening posture, weakly justifying his actions with the excuse, “I only meant to defend myself!” The scene is further amplified by the presence of Vice President Fillmore, depicted using his gavel to attempt to restore order amidst the chaos. A senator in the background pleads desperately for calm, exclaiming, “For God’s sake Gentlemen Order!” Adding to the scene’s political weight, prominent figures like Henry Clay and Daniel Webster are shown observing the spectacle from the sidelines. Clay, known for his wit, offers a sarcastic comment, “It’s a ridiculous matter, I apprehend there is no danger on foot!”, playing on the double meaning of “on foot” to suggest the absurdity of the situation. Finally, the illustration highlights the panic among the onlookers in the Senate galleries, who are depicted fleeing in fear. The overall effect is a humorous yet pointed commentary on the volatile political climate surrounding the issue of slavery and statehood. The cartoon, titled “The Hurly-Burly Pot,” aptly captures the tumultuous nature of the event. This 1850 lithograph is a scathing critique of the divisive political forces threatening the unity of the United States. The artist doesn’t simply depict these factions; he actively condemns them, portraying them as a dangerous threat to the nation’s integrity. Specifically, he targets prominent figures representing various sectionalist viewpoints. The artist chooses to highlight William Lloyd Garrison, a radical abolitionist; David Wilmot, a Pennsylvania advocate for the Free Soil movement; Horace Greeley, a highly influential New York journalist; and John C. Calhoun, a powerful Southern senator championing states’ rights.

These key figures are depicted in a highly symbolic manner. They are shown wearing fool’s caps, suggesting their actions are foolish and misguided, and are gathered around a bubbling cauldron, reminiscent of the witches in Shakespeare’s Macbeth, a clear allusion to brewing trouble. Into this cauldron, they toss sacks representing their respective ideologies: “Free Soil,” “Abolition,” and “Fourierism” (the last added by Greeley, a known proponent of Charles Fourier’s utopian socialist ideas). The cauldron already contains other elements representing various forms of dissent, including “Treason,” “Anti-Rent,” and “Blue Laws,” all contributing to the simmering conflict.

The lithograph further emphasizes the destructive nature of these ideologies through the inclusion of rhyming incantations spoken by each of the three main figures. These verses, filled with calls for division and strife, highlight the artist’s view of their destructive potential. Garrison’s verse, particularly, is infused with hateful racial slurs, reflecting the prevalent racism of the time and the artist’s condemnation of Garrison’s methods. The presence of Calhoun, a prominent figure in the pro-slavery movement, adds another layer of complexity. He acts as a sort of ringleader, invoking the traitor Benedict Arnold as a patron saint, underscoring the artist’s view of these movements as treasonous. Arnold’s appearance from the flames, offering his blessing, solidifies this interpretation.

In essence, the lithograph serves as a powerful visual argument against sectionalism and the various movements contributing to the growing tensions that would eventually lead to the Civil War. The artist uses satire and symbolism to condemn these figures and their ideologies, portraying them as agents of chaos and division, ultimately threatening the very fabric of the American Union. This 1850 illustration presents a controversial perspective on slavery, aiming to undermine the abolitionist stance by contrasting the supposed idyllic life of enslaved people in the American South with the harsh realities faced by the industrial working class in England. The depiction of Southern slavery is incredibly unrealistic; it portrays enslaved individuals merrily dancing and playing while being observed by seemingly approving gentlemen, both Northern and Southern. The dialogue included further reinforces this idealized view. A Northern visitor expresses surprise at the apparent wellbeing of the enslaved, questioning the accuracy of abolitionist reports and suggesting that the conflict could have been avoided with prior knowledge. A Southern planter attributes the slaves’ leisure time to their completion of daily labor, implying a benevolent system. Another Southerner expresses concern about the potential dissolution of the Union but emphasizes the importance of defending Southern rights.

In stark contrast, the illustration presents a bleak picture of English industrial life. The second scene depicts a starkly different reality: a former playmate of a well-dressed gentleman is now an aged and worn factory worker, highlighting the devastating physical toll of factory labor. A destitute mother mourns the suffering of her children, trapped in the cycle of poverty and factory work. The presence of a wealthy clergyman collecting tithes and a fat official collecting taxes underscores the societal inequalities that exacerbate the workers’ plight. The conversation between two young boys reveals their desperate attempts to escape the grueling factory work, even considering the equally harsh conditions of coal mines. The image of a man relieved at the prospect of his imminent release from factory work further emphasizes the oppressive nature of the system. A military camp in the distance hints at the potential for social unrest. This grim portrayal is sourced from Edward Lytton Bulwer’s “England and the English,” published in 1833, highlighting the long-standing awareness of these social issues.

The inclusion of a portrait of George Thompson, a prominent English anti-slavery activist, and a quote from his speech further complicates the illustration’s message. Thompson’s boast that slavery does not exist in England ironically underscores the illustration’s attempt to equate the suffering of English factory workers with that of American slaves, thereby attempting to deflect criticism of the Southern institution. The juxtaposition of these two scenes, one idyllic and the other grim, serves as a deliberate attempt to challenge the prevailing Northern abolitionist narrative, suggesting that the suffering of the industrial poor in England was comparable to, or even worse than, the lives of enslaved people in the South. The illustration’s overall effect is to provoke debate and challenge the simplistic views on both slavery and industrial poverty. This 1850 artwork, imbued with both humor and empathy, depicts the dramatic climax of Henry Brown’s daring escape from slavery. The painting showcases the moment Brown, having endured a harrowing journey crammed inside a small wooden crate, finally emerges in Philadelphia, free from the bonds of Richmond, Virginia. The scene is set within the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society’s office, where onlookers, including the prominent abolitionist Frederick Douglass (shown with a hammer, possibly symbolic of breaking free), witness this triumphant moment.

Brown’s remarkable escape, achieved by having himself shipped as freight via Adams Express, was extensively documented in his 1849 autobiography, a narrative that quickly gained widespread attention. This personal account detailed the extreme physical and mental hardship he endured during his confinement within the three-foot-long, two-and-a-half-foot-deep, and two-foot-wide box. The box itself transcended its literal form, becoming a potent symbol within the abolitionist movement, representing the dehumanizing conditions and spiritual oppression inherent in the institution of slavery. It served as a powerful visual metaphor for the suffocating constraints imposed upon enslaved people. The image, therefore, is not just a depiction of an escape but a visual testament to the struggle against slavery. The artist cleverly uses a seemingly simple scene to convey a profound message about the fight for freedom and the inhumanity of the slave system. The contrast between the cramped confines of the box and the open space of the abolitionist office powerfully underscores the transformation Brown experienced. The inclusion of Douglass further elevates the significance of the event, linking Brown’s escape to the broader abolitionist movement and its key figures. This 1855 portrait depicts Anthony Burns, a fugitive slave whose apprehension and subsequent trial under the harsh Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 ignited significant unrest. The trial, which occurred in the spring of 1854, sparked widespread riots and protests in Boston, fueled by both abolitionists and concerned citizens. The artwork itself is a bust portrait of the 24-year-old Burns, meticulously crafted from a daguerreotype taken by the renowned photographers Whipple and Black. It’s not simply a likeness, however; the portrait is rich with narrative detail.

Surrounding the central image of Burns are vignettes illustrating key moments in his life, arranged in a circular fashion. Starting from the bottom left, we see a depiction of his youthful self being sold at auction, a brutal scene highlighting the inhumanity of slavery. Next, a whipping post stands starkly against bales of cotton, a visual representation of the physical and psychological torment inflicted upon enslaved people. The narrative continues with the depiction of his arrest in Boston on May 24, 1854, a pivotal moment that triggered the aforementioned protests. His daring escape from Richmond aboard a ship is also shown, a testament to his courage and determination. The portrait then contrasts this with his forced departure from Boston, under the heavy guard of federal marshals and troops, a poignant visual of the powerlessness he faced against the law. Another scene shows Burns delivering an address, possibly in court, showcasing his resilience and possibly his attempts at self-defense. Finally, the cycle concludes with an image of Burns imprisoned, encapsulating the tragic reality of his situation.

The portrait’s copyright was registered with the Library of Congress on January 25, 1855, under Burns’s own name. This was a common tactic employed by abolitionists; registering copyrighted works, such as prints and pamphlets, under the subject’s name was a strategic move to amplify their cause and ensure the subject’s story was preserved. This is particularly significant considering that by 1855, Burns had already been forcibly returned to his enslaver in Virginia, highlighting the powerlessness of even a publicized struggle against the Fugitive Slave Act. The act of copyrighting the portrait in his name, therefore, serves as a lasting testament to the abolitionist movement’s commitment to his memory and their fight against the injustices of slavery. This 1856 artwork dramatically depicts the violent clash in the US Congress that severely escalated tensions between the North and South. The image vividly recreates the brutal assault on Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts by Representative Preston Brooks of South Carolina on May 22nd. Brooks’s attack was a direct response to a fiery anti-slavery speech Sumner delivered just two days prior, where he harshly criticized Brooks’s cousin, Senator Andrew Butler, and Senator Stephen Douglas.

The print itself shows the moment of the attack, capturing Brooks, enraged, looming over the unsuspecting Sumner, who is seated at his desk, seemingly engrossed in writing. Brooks is poised to strike Sumner with his cane. The scene is further charged by the presence of Brooks’s accomplice, Representative Lawrence Keitt, also from South Carolina, who aggressively brandishes his own cane, threatening potential interveners among the other senators. The lack of immediate assistance for Sumner is palpable. Adding to the tension, Keitt is secretly armed with a pistol, concealed in his hand.

In the foreground, we see Senators Robert Toombs of Georgia and Stephen Douglas of Illinois, their expressions suggesting approval of the attack. Their presence underscores the deep sectional divisions. Further back, the scene includes the restrained figure of Senator John Crittenden of Kentucky, held back by an unidentified individual. This detail highlights the widespread impact and the polarized reactions to the event.

The artwork’s title is overlaid with a quote from a speech given by Henry Ward Beecher at a rally supporting Sumner. Beecher’s words, “The symbol of the North is the pen; the symbol of the South is the bludgeon,” encapsulate the prevailing sentiment of the time, framing the conflict as a clash between intellectual discourse and physical violence, representative of the contrasting values and approaches of the North and South. The image itself serves as a powerful visual commentary on this deeply divisive moment in American history. This 1862 lithograph depicts a pointed critique of Senator Charles Sumner, a leading figure in the abolitionist movement. Instead of portraying Sumner as a champion of all the downtrodden, the image subtly undermines his humanitarian image. The artist achieves this by showing Sumner offering a paltry sum of money to a Black child, a gesture that appears condescending and insufficient. Simultaneously, the senator pointedly ignores a much more desperate plea from a poor white child, highlighting a perceived hypocrisy in Sumner’s selective compassion. Two elegantly dressed women observe this scene, their presence possibly suggesting the societal indifference to the plight of the poor, regardless of race. While the print lacks a signature, its artistic merit – the skill in rendering the figures and the evocative atmosphere – strongly suggests the hand of Boston lithographer Dominique Fabroniust. The composition itself functions as a visual argument, questioning Sumner’s genuine commitment to humanitarian ideals and implying that his abolitionist stance might be driven by factors other than pure altruism. The contrast between the carefully rendered clothing of the women and the ragged appearance of the children further emphasizes the social stratification and the artist’s critique of Sumner’s apparent lack of concern for the broader spectrum of poverty. The overall effect is a subtle but powerful indictment of Sumner’s actions and, by extension, perhaps the limitations of the abolitionist movement itself. This 1863 etching serves as a powerful and scathing critique of Jefferson Davis and the institution of slavery in the South. Instead of a single image, the artwork is a series of twelve small pictures, or vignettes, each accompanied by a short poem. The structure cleverly mimics the cumulative style of the children’s rhyme “The House That Jack Built,” a structure also previously employed in political satires of the Jacksonian era. This familiar framework allows the artist to build a progressively damning case against the Confederacy and its leaders.

The etchings depict a horrifying progression: starting with the literal “house” – a slave pen’s entrance – the images escalate to show the cotton production fueled by enslaved labor (“By rebels call’d king”), the enslaved people themselves toiling in the fields (“field-chattels that made cotton king”), and the despair of families facing the horrors of slave auctions. Further vignettes illustrate the dehumanizing aspects of the system: the auctioneer, reduced to “the thing by some call’d a man,” the instruments of torture (shackles and the cat-o’-nine-tails), and the brutal slave traders. A scene depicting a slave breeder negotiating with a merchant, with portraits of Davis and Beauregard on the wall, directly implicates these Confederate leaders in the system’s cruelty. The climax shows a brutal whipping of a bound woman, culminating in a final image of Jefferson Davis himself, condemned as the architect of this evil (“the arch-rebel Jeff whose infamous course / Has bro’t rest to the plow, and made active the hearse”). The concluding vignette displays broken symbols of slavery – the gavel, whip, and shackles – alongside a notice announcing Davis’s execution, symbolizing the ultimate downfall of the Confederacy and its oppressive system (“… Jeffs infamous house is doom’d to come down”). The title, “The Great American What Is It? Chased By Copper-Heads,” further suggests the artist’s view of the Confederacy as a monstrous entity hunted down by Union forces (the “Copper-Heads” being a derogatory term for Northerners sympathetic to the Confederacy). This 1863 satirical cartoon, a potent critique of Abraham Lincoln and the Republican party, depicts the president and his supporters under attack by monstrous “Copperheads,” a derogatory term for Peace Democrats who opposed the Civil War. The image directly references the arrest and trial of Clement Vallandigham, a prominent Copperhead leader. Vallandigham, after a speech arguing the war was about enslaving whites rather than freeing blacks and preserving the Union, was arrested for violating General Order No. 38, which prohibited expressing sympathy for the enemy. While initially sentenced to imprisonment, Lincoln commuted his sentence to exile in the Confederacy due to Vallandigham’s considerable public support.

The cartoon visually represents this conflict. Lincoln, depicted in simple attire, is pursued by enormous copperheads, symbolizing the political threat posed by the Peace Democrats. He’s shown discarding a document titled “New Black Constitution,” signed “A. L. & Co.”, highlighting the controversial Emancipation Proclamation and its perceived threat to the established social order. The Copperheads taunt him, reflecting the racist sentiments prevalent within the Peace Democrat movement. The inclusion of freedmen pleading with Lincoln, a fleeing black man from Lincoln’s hat, and a snake devouring a black man underscores the cartoonist’s commentary on the racial dynamics of the war and the anxieties surrounding emancipation.

General Ambrose Burnside, known for his strict enforcement of wartime restrictions, is shown being strangled by a snake representing Vallandigham, a visual representation of the political struggle between the Union’s hardline approach and the Peace Democrats’ opposition. The burning torch he holds, possibly alluding to the Wide-Awakes, a pro-Lincoln political organization, adds another layer of political symbolism, though its exact meaning remains ambiguous.

The cartoon further incorporates the specter of John Brown, the abolitionist martyr, rising from his grave, a symbol of the radical abolitionist movement. Satan’s urging of Brown towards Canada suggests a connection between abolitionist ideals and the perceived threat of Northern radicalism. The inclusion of a deformed African man, referencing P.T. Barnum’s museum, adds a layer of social commentary, highlighting the exploitation and dehumanization of African Americans during this era. The overall effect is a complex and multi-layered critique of the political and social climate of the Civil War, using visual metaphors to express the artist’s perspective on Lincoln, the war’s aims, and the political opposition. The Chicago Platform, adopted by the Populist Party at their national convention in 1892, served as a powerful articulation of the agrarian unrest sweeping across the United States at the time. It wasn’t merely a list of demands; it represented a comprehensive critique of the existing economic and political system, blaming it for the hardships faced by farmers and working-class citizens. Instead of simply stating grievances, the platform offered a detailed vision for reform, aiming to fundamentally shift the balance of power in favor of the common person.

The document’s core tenets centered on the belief that concentrated wealth and corporate power were stifling economic opportunity and democratic participation. In essence, the Populists argued that the existing system, dominated by powerful industrialists and financiers, was rigged against the average citizen. They didn’t just feel marginalized; they felt actively exploited. This feeling of exploitation fueled their calls for significant changes to the financial and political landscape.

The platform advocated for a range of reforms, including the nationalization of railroads and communication systems, believing that these essential services should be publicly owned and operated to ensure fairness and affordability. This was a direct challenge to the laissez-faire capitalism that dominated the era, which prioritized private profit over public good. Furthermore, the Populists championed the free and unlimited coinage of silver, aiming to inflate the money supply and alleviate the burden of debt on farmers. This monetary policy was seen as a crucial step towards economic justice.

Beyond economic policy, the Chicago Platform also addressed political reforms. It called for initiatives like the direct election of senators, aiming to increase the responsiveness of government to the needs of the people. In essence, they sought to weaken the power of political machines and entrenched interests that often ignored the voices of ordinary citizens. The platform also advocated for a graduated income tax, a progressive measure aimed at redistributing wealth and reducing economic inequality.

In conclusion, the Chicago Platform wasn’t simply a political document; it was a social and economic manifesto. It reflected the deep-seated anxieties and frustrations of a population feeling increasingly powerless in the face of rapid industrialization and economic consolidation. Its proposals, though ultimately unsuccessful in achieving their immediate goals, significantly influenced the progressive movement of the early 20th century and left a lasting mark on American political thought. This 1864 illustration by Thomas Nast is a cleverly disguised political cartoon, seemingly supporting George B. McClellan’s presidential campaign but actually fiercely criticizing the Democratic Party platform. The central image depicts McClellan passively observing the disastrous Battle of Malvern Hill, a key defeat from his Peninsula Campaign, highlighting his perceived inadequacy as a military leader. The title, “The Chicago Platform,” ironically juxtaposes the Democratic Party’s claims with the reality of their policies as depicted in the accompanying illustrations. The subtitle, “Union Failures,” further underscores Nast’s satirical intent. A cannon surrounded by tattered American flags visually reinforces this theme of national weakness under Democratic leadership.

Each section of the cartoon visually contradicts a corresponding point in the Democratic platform. For instance, the resolution pledging unwavering fidelity to the Union is countered by an image of a Black man pursued by bloodhounds, illustrating the party’s perceived hypocrisy regarding racial equality. Similarly, the Democratic condemnation of military interference in elections is juxtaposed with a scene of Union soldiers ensuring fair voting, while excluding an unruly Irishman, implying Democratic support for voter suppression. Another section, depicting Lincoln presenting the Emancipation Proclamation to freed slaves, directly refutes the Democratic claim of upholding the Constitution, suggesting that the Democrats’ actions disregarded the principles of liberty and equality.

The cartoon also depicts the brutal realities of the New York Draft Riots of 1863, showcasing violence against both Black people and those perceived as anti-war, directly contradicting the Democratic party’s claimed commitment to preserving the Union and individual rights. The image of a simian-like Irishman abusing a Black child further emphasizes the cartoon’s critique of the Democratic Party’s tolerance of racial violence and prejudice. The claim that the Democratic Party aimed to preserve the Federal Union and states’ rights is countered by images of slave auctions and whippings, exposing the inherent contradiction in their platform.

Finally, the bottom of the cartoon presents a series of scenes depicting various aspects of the war, including Confederate soldiers pledging allegiance to Jefferson Davis, a Union graveyard representing the war’s casualties, and the arrest of suspected Northern spies (“Rebels in the North”), all serving to highlight the Democratic Party’s perceived failure to effectively manage the conflict and its potential complicity with the Confederacy. The inclusion of excerpts from McClellan’s acceptance speech and Pendleton’s pro-reconciliation speech further underscores the cartoonist’s condemnation of the Democratic platform as weak and potentially treasonous. In essence, Nast’s illustration is a powerful visual indictment of the Democratic Party’s stance during the Civil War, using imagery to expose the hypocrisy and dangerous implications of their policies. This 1866 political cartoon, part of a series attacking Radical Republicans and promoting white supremacy during the Pennsylvania gubernatorial election, depicts the Freedman’s Bureau as a corrupt and wasteful organization that encourages black idleness at the expense of white taxpayers. The image uses stark contrasts to convey its message. While one white man toils in the fields and another chops wood, a Black man lounges, seemingly unconcerned with labor. This scene is juxtaposed with biblical text (“In the sweat of thy face shalt thou eat thy bread”) highlighting the perceived unfairness of the situation. The caption accompanying the Black man emphasizes his supposed belief that government aid negates the need for work.

The cartoon further vilifies the Freedman’s Bureau by portraying it as a lavish building, resembling the U.S. Capitol, but instead of representing government, it’s adorned with labels signifying indulgence and idleness: “Candy,” “Rum, Gin, Whiskey,” “Sugar Plums,” and so on. The implication is that the Bureau’s funds are being squandered on frivolous luxuries for Black people, rather than being used for their genuine uplift. The inclusion of “White Women” among these labels adds a layer of racist innuendo, suggesting illicit relationships and moral decay. The accompanying chart reinforces this narrative by highlighting the financial burden on white taxpayers, contrasting it with alleged preferential treatment of Black veterans in terms of Civil War bounties.

The overall message is clear: the Democratic candidate, Hiester Clymer, is presented as the champion of the “White Man,” advocating for policies that would protect white interests and prevent the perceived misuse of taxpayer money. His opponent, James White Geary, is conversely portrayed as favoring Black people at the expense of whites. The series, which includes other pieces like “The Two Platforms” and “The Constitutional Amendment!”, serves as a powerful example of the racist propaganda used during Reconstruction to sway public opinion and undermine the efforts of those advocating for racial equality. The cartoon’s impact lies in its visual simplicity and its effective use of racist stereotypes to demonize the Freedman’s Bureau and promote a white supremacist agenda. The connection to the “Massacre at New Orleans” is not directly made within the provided text, suggesting a separate incident or context. In an 1867 artwork, the renowned political cartoonist Thomas Nast depicted President Andrew Johnson in regal attire – a king adorned in velvet and ermine – a visual metaphor for Johnson’s purported monarchical aspirations, a theme frequently exploited by his political opponents. This satirical portrayal stemmed from the widespread accusations leveled against Johnson for inciting the violent New Orleans race riot of July 1866, where numerous African American delegates attending a Republican convention were fatally shot by police. Nast’s depiction served as a scathing indictment of Johnson’s perceived role in this tragedy.

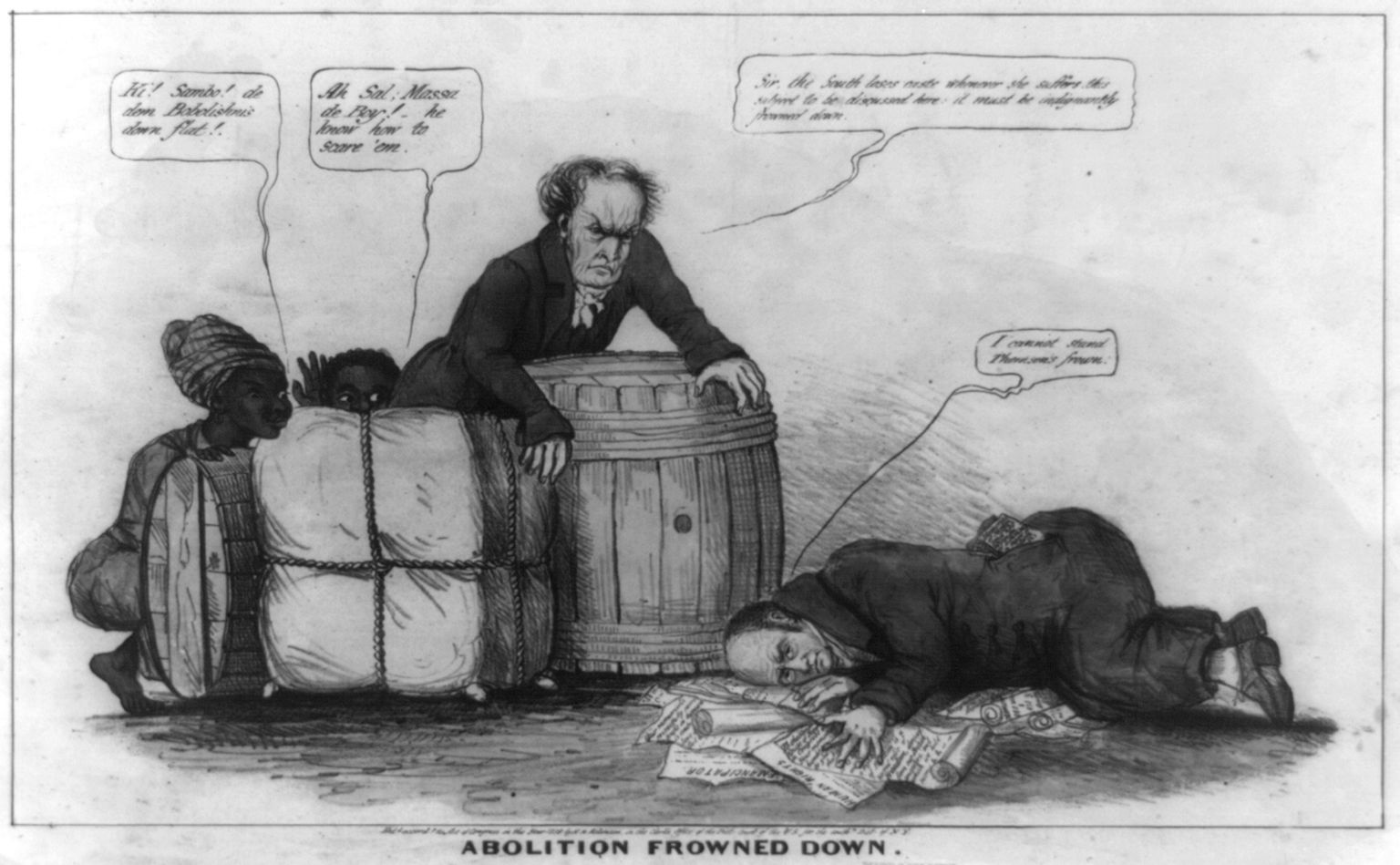

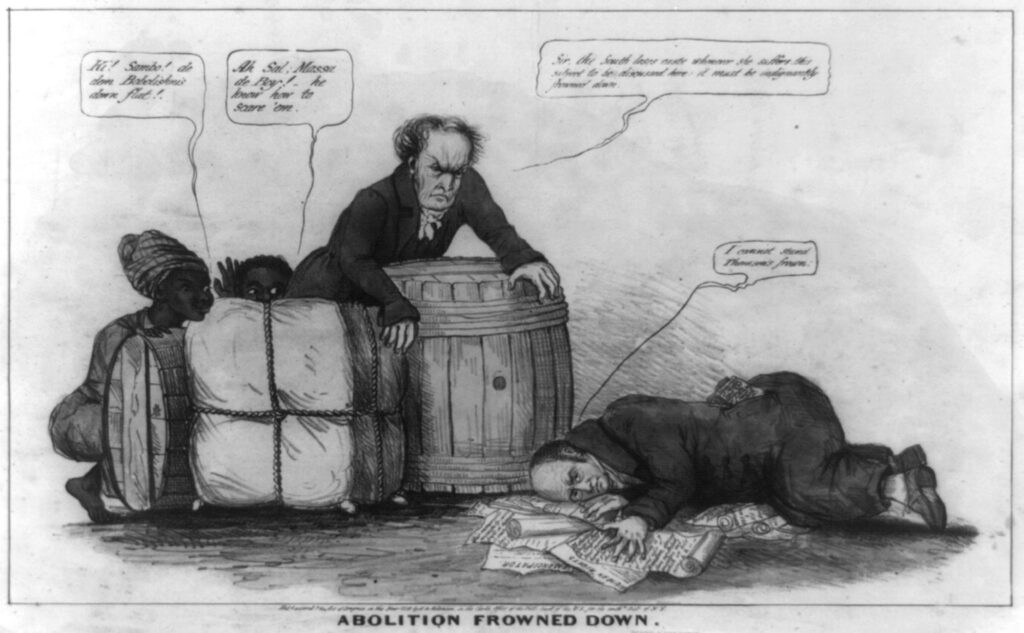

This particular painting is one of only five surviving pieces from Nast’s ambitious Grand Caricaturama, a large-scale, humorous, and theatrical presentation of American history. This historical review blended real individuals with allegorical figures. The Caricaturama comprised 33 enormous paintings, each measuring approximately eight by twelve feet, designed for a dynamic stage display. The presentation was presented as a moving panorama, enhanced by a narrated explanation and musical accompaniment from a piano. The tour, which included performances in New York City and Boston, was met with enthusiastic popular acclaim, demonstrating the significant public interest in Nast’s satirical commentary on contemporary political events. The smaller sample images provided here only offer a limited glimpse of the scale and impact of the original works. The detail from “Abolition Frowned Down” further illustrates Nast’s powerful and often controversial style. This 1839 satirical illustration lampoons the suppression of slavery debate in the U.S. House of Representatives through the infamous “gag rule.” The image cleverly captures the escalating tensions of the era. The growing abolitionist movement in the North directly clashed with the increasingly defensive stance of Southern representatives who viewed any discussion of slavery as intrusive and offensive to their constituents.

The artwork likely depicts either John Quincy Adams’s initial opposition to the 1838 gag rule or, more probably, his continued defiance in 1839 as he relentlessly attempted to bring the plight of enslaved people to the forefront by presenting petitions from Northern citizens. A new, stricter gag rule was enacted in December 1839, completely silencing any mention of abolition within the House—no debate, no reading of petitions, no printing of related material, and absolutely no references whatsoever.

The illustration shows Adams, humiliated and defeated, lying prostrate on a mound of petitions, an abolitionist newspaper (“The Emancipator”), and a resolution advocating for Haitian recognition. His dejected words, “I cannot stand Thomson’s frown,” reveal his subjugation to the powerful anti-abolitionist forces. South Carolina Representative Waddy Thompson Jr., a prominent Whig and staunch defender of slavery, is depicted menacingly looming over Adams, his words, “Sir, the South loses caste whenever she suffers this subject to be discussed here; it must be indignantly frowned down,” encapsulating the South’s unwavering determination to maintain the status quo. Two Black figures are shown cowering behind Thompson, their comment, “de dem Bobolishn is down flat!”, highlighting the silencing of abolitionist voices.

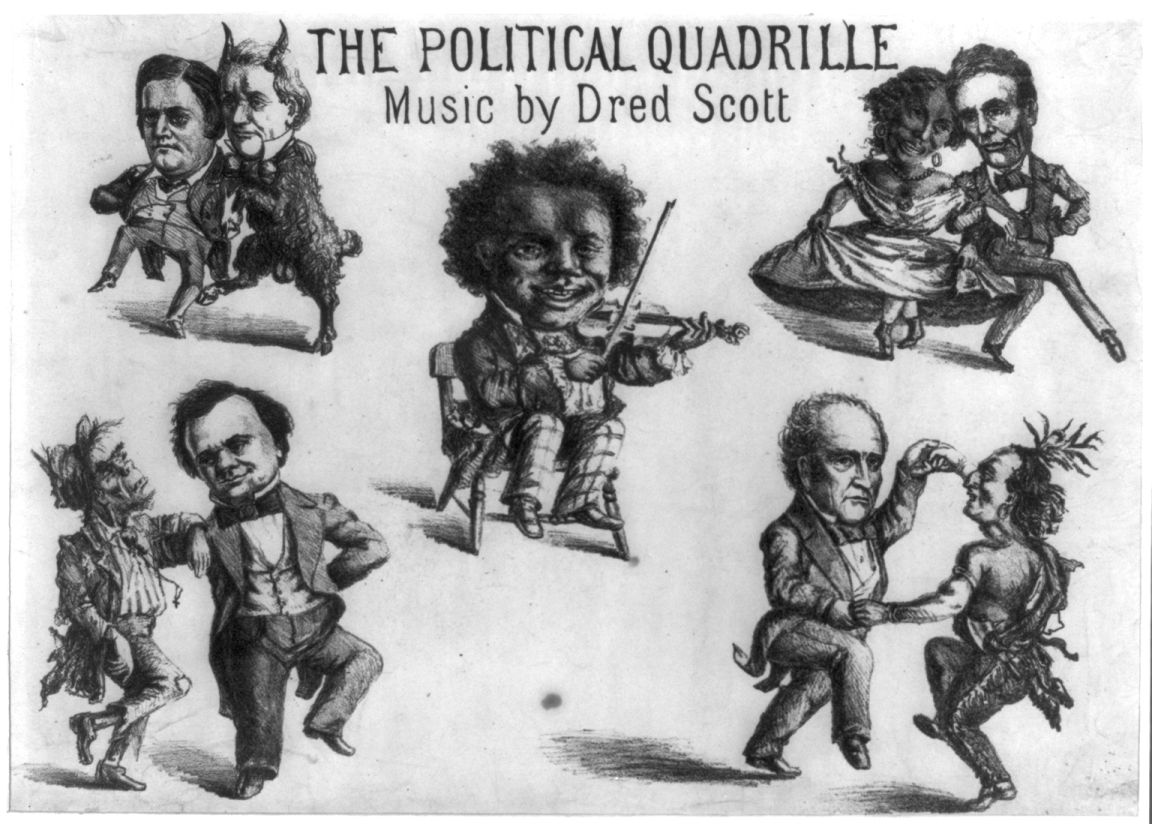

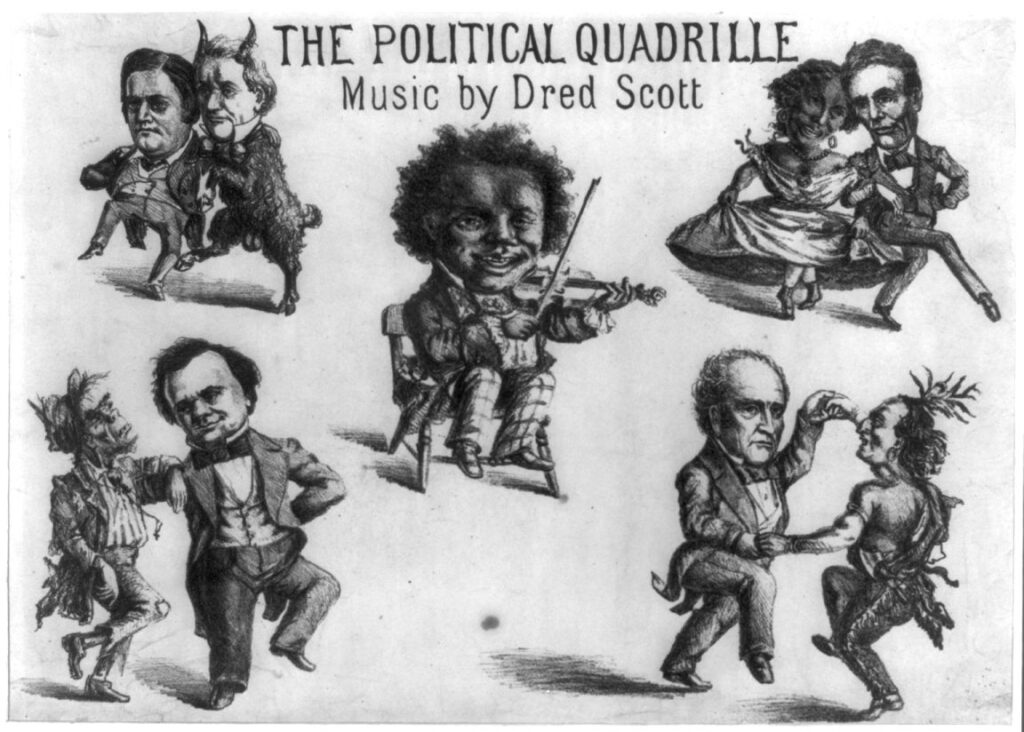

Finally, the print’s provenance is noted. Scholar Frank Weitenkampf, a former curator at the New York Public Library, identified a version bearing the imprint of Robinson as printer and publisher, a detail absent from the Library of Congress’ copy, suggesting a variation in the prints’ original publication. The image’s title, “The Political Quadrille. Music by Dred Scott,” further underscores the political maneuvering and the inescapable presence of slavery in the nation’s political discourse, referencing the infamous Dred Scott Supreme Court case. This 1860 lithograph isn’t just a picture; it’s a satirical commentary on the fiercely contested presidential election of that year, specifically focusing on how the Dred Scott Supreme Court decision profoundly impacted the race. The 1857 Dred Scott ruling, a deeply divisive judgment by Chief Justice Roger B. Taney, declared that neither the federal government nor any territorial government possessed the authority to outlaw slavery in U.S. territories. This ruling directly fueled the already intense debate surrounding the future of slavery in the nation, a central topic for all the 1860 presidential candidates.

The lithograph depicts the four main candidates engaging in a lively dance, each paired with a representative figure from their supposed voter base. At the heart of the scene sits Dred Scott himself, the former slave whose legal case was the catalyst for the controversial Supreme Court decision, playing the fiddle for this unusual political ball. In the upper left, we see Southern Democrat John C. Breckinridge dancing with James Buchanan, the incumbent Democratic president, portrayed as a goat, a common derogatory nickname for him. In the upper right, Republican Abraham Lincoln is shown dancing with a Black woman, a clear and offensive allusion to the Republican Party’s association with the abolitionist movement. The image in the lower right shows John Bell, the Constitutional Union candidate, dancing with a Native American, a pairing whose meaning is less clear but might suggest Bell’s fleeting attempts to appeal to Native American interests. Finally, in the lower left, Stephen A. Douglas is depicted dancing with a ragged Irishman, a common visual trope associating Douglas with the Irish immigrant vote and hinting at accusations of his Catholicism. This Irishman, frequently seen in cartoons alongside Douglas (as in “The Undecided Political Prize Fight”), carries a cross, reinforcing this symbolic connection.

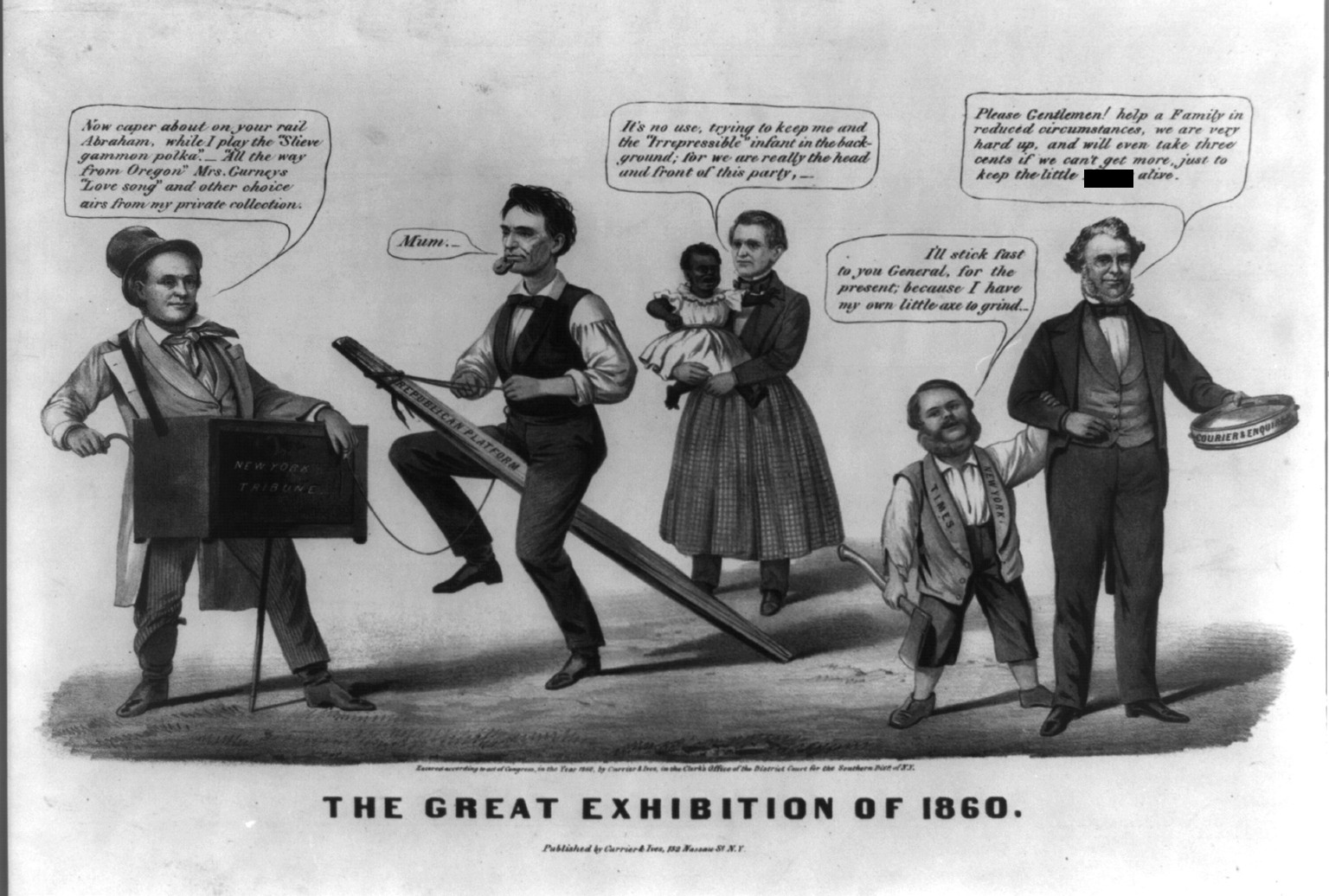

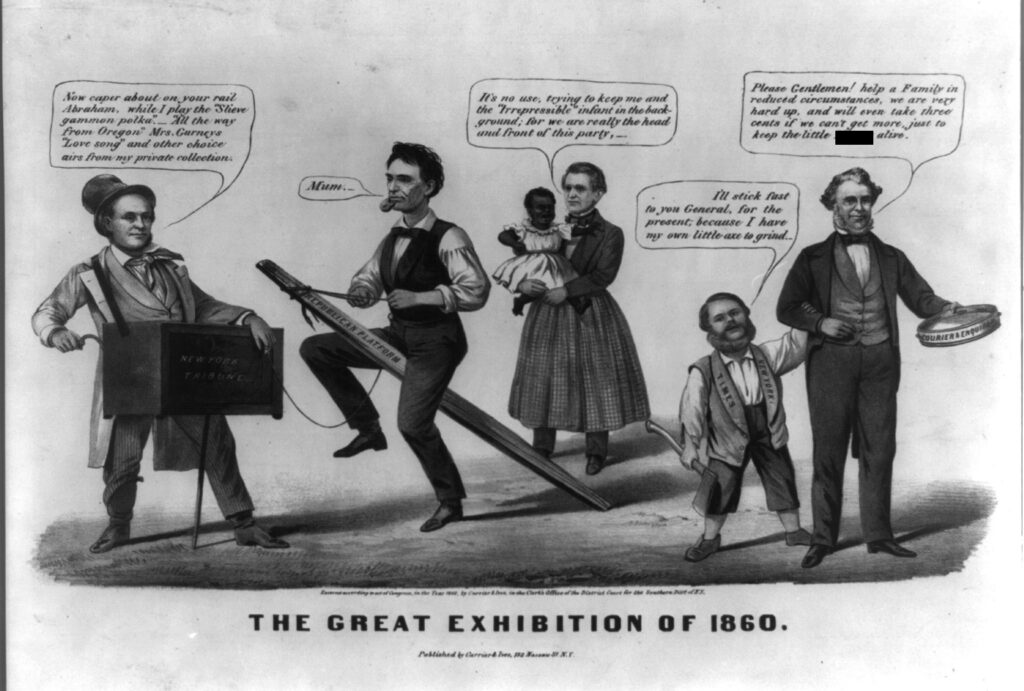

The lithograph, therefore, uses the visual language of caricature and satire to comment on the political landscape of 1860, highlighting the racial tensions and the significant role of the Dred Scott decision in shaping the election. It’s important to note that the original image contains a racial slur, which has been obscured in this description for sensitivity reasons. The uncensored version, however, is available in its original form. The lithograph’s appearance in the Great Exhibition of 1860 suggests its relevance and widespread circulation at the time. This 1860 satirical print mocks the Republican Party’s stance on slavery, a position that, while prominent, the party attempted to downplay during their 1860 campaign. The image depicts a caricatured scene where the influential abolitionist Horace Greeley, editor of the New York Tribune, is depicted as the puppeteer controlling Abraham Lincoln, the Republican presidential candidate. Greeley, shown grinding his newspaper like an organ, literally pulls the strings of Lincoln, who is figuratively bound and silenced, forced to perform a frivolous dance on a wooden rail – a symbol of his campaign. Greeley’s gleeful instruction to Lincoln highlights the artist’s suggestion that Lincoln’s campaign is orchestrated by radical abolitionists. Lincoln’s inability to speak underscores the suppression of his own views on slavery.

The print further satirizes the prominent role of abolitionism within the Republican party through the inclusion of William H. Seward, a key Republican figure, who is shown cradling a crying black baby, representing the “Irrepressible Conflict” – the unavoidable clash between slavery and freedom. Seward’s lament about being relegated to the background ironically underscores his actual importance within the party.

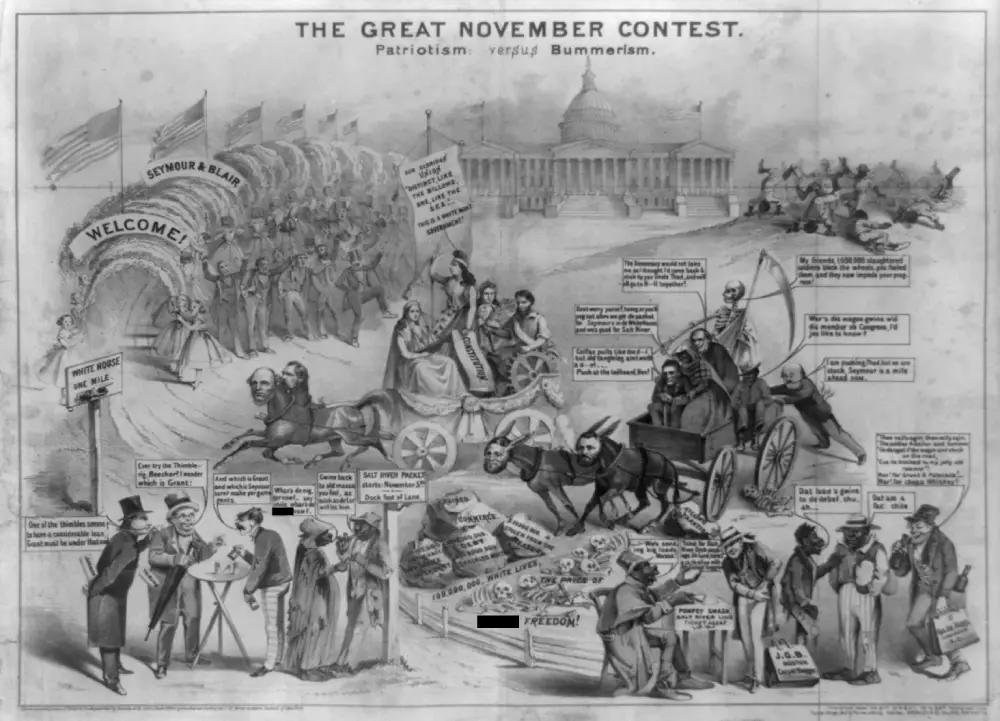

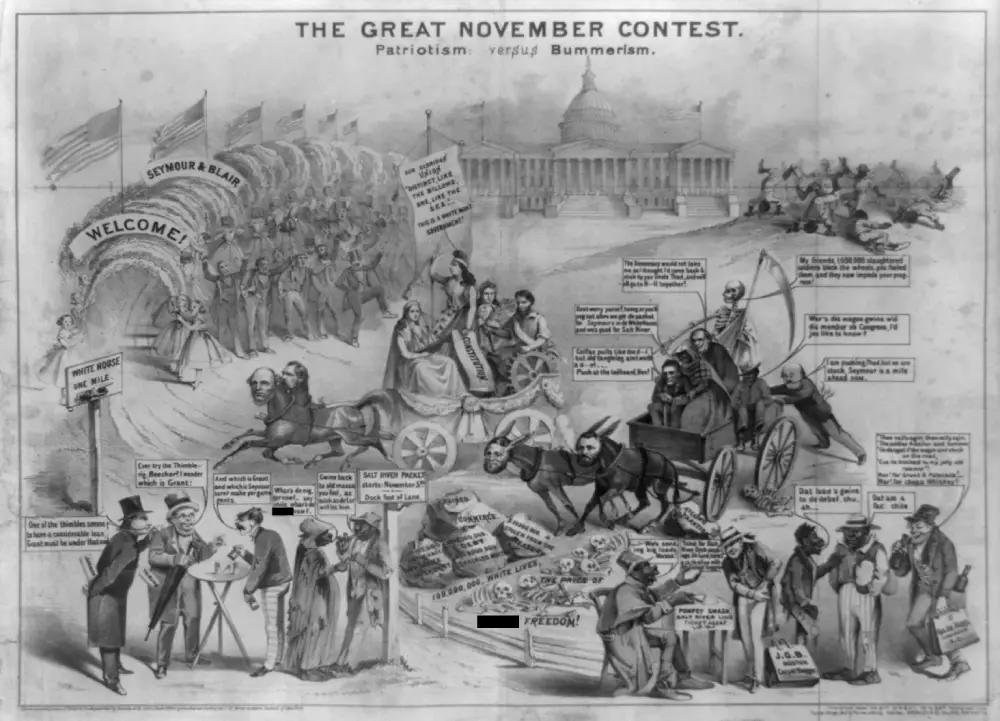

The remaining figures, Henry J. Raymond and James Watson Webb, both New York newspaper editors supportive of the Republicans, represent further elements of the satire. Raymond, depicted with an axe, metaphorically represents his ambition and self-interest within the party. His clinging to Webb highlights their past professional relationship and suggests a dependence on each other. Webb, struggling financially, uses a tambourine to solicit donations, symbolizing his newspaper’s precarious financial state and the desperate measures he took, including reducing the price to three cents, to maintain circulation. The artist’s inclusion of a racial slur in Webb’s plea further emphasizes the desperation and the exploitation of the situation. The overall effect is a humorous yet pointed critique of the Republican Party’s internal dynamics and its strategic handling of the slavery issue during the 1860 election. The provided text refers to an image, “slaverycartoons4,” containing obscured racial slurs. This suggests the image is a piece of historical propaganda, likely from a time when such language was commonplace and acceptable within certain circles. The obscuring of the slurs in this particular instance implies a degree of sensitivity or editorial intervention in the presentation of the image, possibly for modern audiences. The fact that the original, uncensored version exists on a disc indicates that the obscured version is a curated or modified presentation.

The phrase “The Great November Contest. Patriotism: Versus Bummerism” suggests the context of the image. It appears to be related to a competition or campaign during November, framing the contest as a clash between patriotism and a less-defined concept, “bummerism,” which might represent apathy, dissent, or anti-patriotic sentiment. This further reinforces the idea that the image is likely a piece of political or social commentary, possibly from a period of significant social or political division. The use of such inflammatory language and imagery within the context of a competition highlights the intensity of the debate and the potential for the image to be used as a tool for persuasion or propaganda. The existence of the uncensored version implies a willingness to utilize highly offensive language to achieve a particular political or social goal. The 1868 lithograph serves as a potent visual representation of the deeply prejudiced nature of the Democratic Party’s presidential campaign that year. This is clearly shown through a comprehensive and elaborate assault on Reconstruction policies and the Republican Party’s advocacy for Black civil rights. The image depicts a symbolic race: a lavish carriage, pulled by horses with the heads of Democratic candidates Horatio Seymour and Francis P. Blair Jr., competes against a dilapidated wagon drawn by donkeys bearing the likenesses of Republican candidates Ulysses S. Grant and Schuyler Colfax. The Democratic carriage, representing elegance and progress, easily outpaces the struggling Republican wagon, reaching a jubilant crowd and a celebratory display near the U.S. Capitol building. Inside the carriage are figures representing ideals associated with the Democrats: Liberty, upholding a banner declaring white male dominance; Navigation, Agriculture, and Labor, symbolizing economic prosperity.

In stark contrast, the Republican wagon is mired in obstacles, including a large stone labeled “Killing Taxation,” symbolizing economic hardship, and a graveyard representing the supposed cost of Black freedom. The wagon’s occupants reflect the Democratic portrayal of the Republicans: the grim reaper, Thaddeus Stevens (a prominent abolitionist), an unidentified figure, a Black woman, and an idle Black man, all suggesting chaos and failure. The dialogue between Stevens and Benjamin F. Butler, another prominent Republican, highlights their perceived inadequacy and inability to compete with the Democrats’ apparent success. Butler’s visible silver spoons further satirize his perceived wealth and detachment from the plight of the common man. The lithograph’s overall message is a blatant attack on Republican policies, using racial stereotypes and exaggerated imagery to demonize the party and its support for Black rights. The visual rhetoric employed is designed to sway public opinion by associating the Republicans with economic ruin and the Democrats with national unity and prosperity. This cartoon, titled “Congressional Scales: A True Balance,” uses allegorical imagery to satirize the political climate following the American Civil War. A black woman comforts a worried Stevens (likely Thaddeus Stevens, a prominent Radical Republican), assuring him that despite current anxieties, their political agenda will ultimately succeed, even if it means facing significant setbacks (“political disaster,” represented by “Salt River”). Her words offer a sense of defiant optimism in the face of adversity.

The query from a black man highlights the uncertainty and skepticism surrounding the political alliance, questioning the wisdom of their association with a particular member of Congress. This reflects the complex and sometimes uneasy relationship between different factions within the movement for racial equality.

The declaration of an unidentified man, pledging loyalty to “Uncle Thad” (Stevens) and accepting the potential for collective failure (“we’ll all go to H-ll together”), underscores the high stakes and the perceived risks of their political endeavors. His decision to align himself with Stevens, despite previous rejection by the Democratic party, speaks to the deep divisions within the political landscape.

Death’s dramatic intervention, highlighting the immense loss of life during the war (“1,000,000 slaughtered soldiers”), serves as a stark reminder of the human cost of the conflict and the obstacles to progress. The implication is that the political maneuvering depicted is occurring despite, or perhaps even at the expense of, the sacrifices made.

The depiction of “bummers” lining up to buy tickets to “Salt River” satirizes opportunistic individuals who profit from political turmoil. These are the political opportunists who would exploit the situation for personal gain, regardless of the consequences.

The scene of Greeley and Beecher playing thimblerig represents the manipulation and deception within the political sphere. This suggests that even prominent figures, associated with abolitionism, are not immune to questionable practices.

The contrast between the impoverished black couple longing for the familiar oppression of their former master and the jubilant black youths dancing near the Capitol building illustrates the stark realities of post-war life. It highlights the divisions within the black community and the differing responses to freedom and the uncertain future.

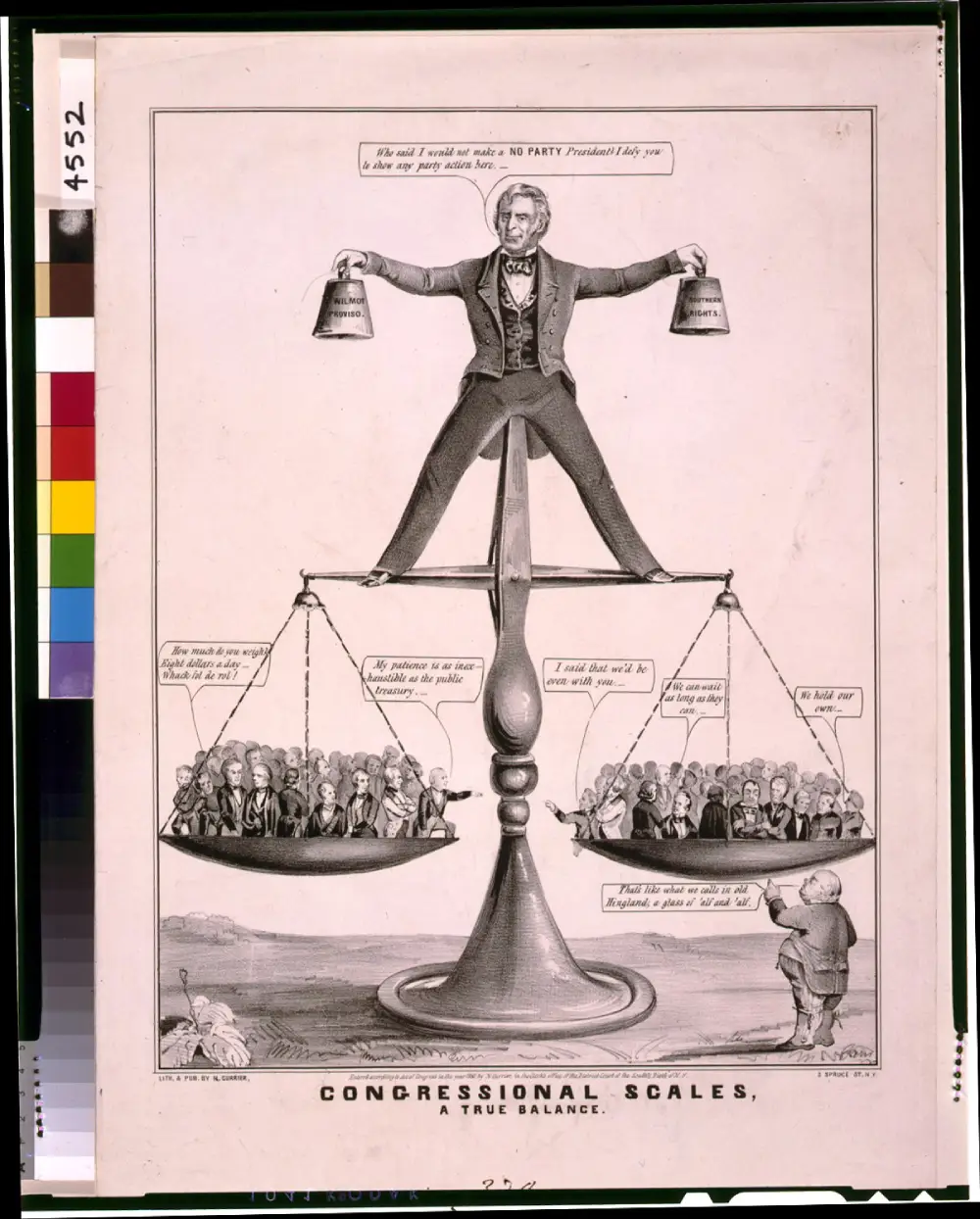

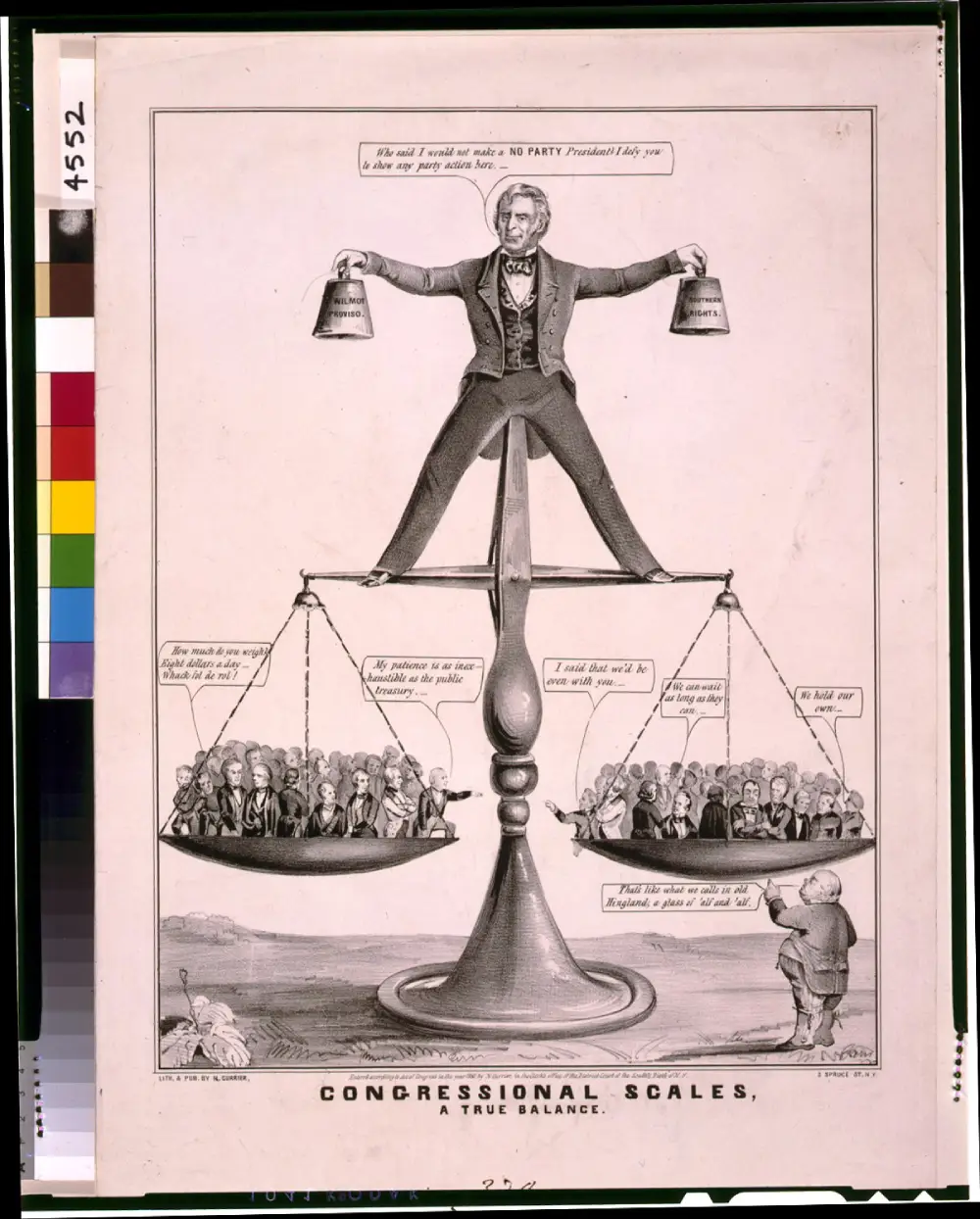

In summary, the cartoon employs a complex array of symbols and characters to critique the political machinations of Reconstruction, highlighting the anxieties, uncertainties, and moral ambiguities of the era. It uses humor and exaggeration to comment on the various players and their motivations, while also acknowledging the profound human cost of the conflict and the challenges facing the nation in its aftermath. This 1850 lithograph satirizes President Zachary Taylor’s efforts to reconcile the conflicting viewpoints of the North and South regarding slavery. The image depicts Taylor precariously balanced on a set of scales, symbolizing his attempt to maintain equilibrium between opposing forces. In his hands, he holds weights representing the “Wilmot Proviso” (representing Northern anti-slavery sentiment) and “Southern Rights” (representing pro-slavery interests). The scales are depicted as perfectly balanced, reflecting Taylor’s claim of neutrality.

Beneath Taylor, the scale’s trays hold prominent figures from Congress. The left tray, associated with the North, includes Henry Clay and others, while the right, representing the South, features Lewis Cass and John Calhoun. This visual arrangement underscores the political maneuvering and delicate balance required to address the slavery issue.

Taylor’s boast, “Who said I would not make a ‘NO PARTY’ President? I defy you to show any party action here,” highlights his attempt to present himself as an impartial leader, above partisan politics. However, the cartoon subtly mocks this claim, suggesting that his balancing act is precarious and unsustainable.

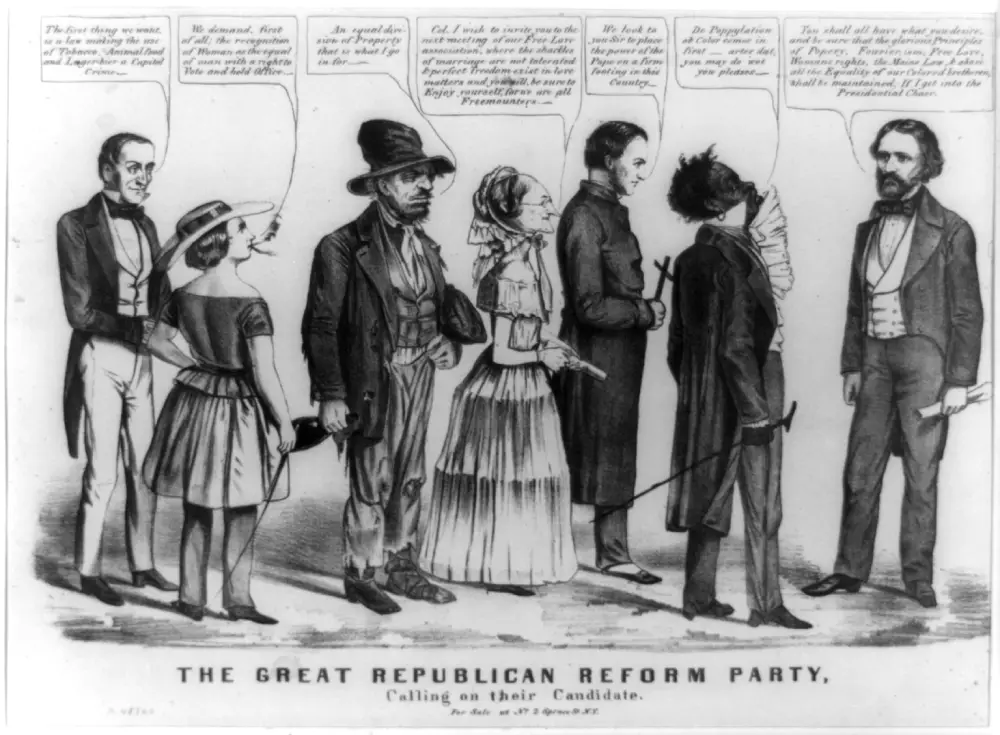

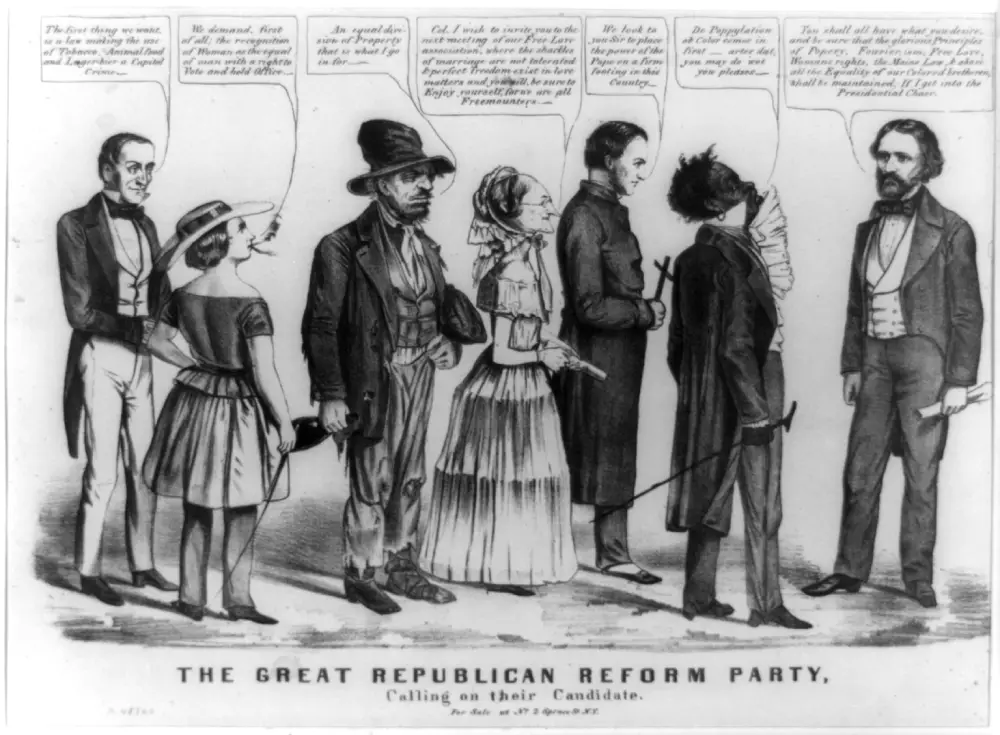

The inclusion of smaller details further enhances the satirical effect. A congressman on the left jokingly sings about his salary, highlighting the financial aspects of political life. Another expresses seemingly endless patience, hinting at the protracted nature of the political debate. A Southern congressman echoes this sentiment, emphasizing the stalemate. Finally, the observation by John Bull, a personification of Great Britain, suggests that this political deadlock is viewed as a compromise, even if a somewhat unsatisfactory one, from an outside perspective. The overall message is one of political tension and the difficulty of navigating the highly charged issue of slavery in the United States. This 1856 lithograph by Louis Maurer depicts John C. Frémont, a presidential candidate, surrounded by a diverse and somewhat satirical collection of 19th-century reform movements. Instead of presenting a unified front, the image highlights the disparate and potentially conflicting agendas of his supporters. The artist cleverly uses caricature to emphasize the incongruity of their various demands.

The temperance advocate, for instance, proposes draconian measures, advocating the death penalty for the use of tobacco, meat, and beer—a wildly impractical and extreme position. A woman, depicted in trousers, a bold statement for the time, represents the burgeoning women’s suffrage movement, demanding equal rights and political participation. A ragged figure, presumably a socialist, calls for an equal distribution of wealth, a radical idea that threatened the existing economic order. An older woman, representing libertarian ideals, invites Frémont to a “Free Love” association meeting, showcasing the movement’s focus on challenging traditional marriage norms. A Catholic priest, surprisingly, seeks Frémont’s support for strengthening the Pope’s influence in America. Finally, a free Black man prioritizes the abolition of slavery and racial equality.

Frémont’s response, “You shall all have what you desire,” is both a promise and a pointed commentary. His pledge to uphold the “glorious Principles of Popery, Fourierism, Free Love, Woman’s Rights, the Maine Law, & above all the Equality of our Colored brethren,” if elected, underscores the wide range of ideologies seemingly coalescing around his candidacy. The artist subtly mocks this broad appeal, suggesting that such a diverse coalition might be inherently unstable and possibly unrealistic. The lithograph serves as a visual commentary on the political landscape of the time, highlighting the various social and political movements vying for influence and the potential for conflict inherent in such a broad-based alliance. The image, therefore, is not simply a portrait of Frémont but a satirical representation of the complex and often contradictory nature of American reform movements in the mid-1800s. The “Secret Confederate Illustrations” label suggests that this piece might have been intended as political propaganda, perhaps to discredit Frémont by showcasing the seemingly incompatible nature of his supporters. This description details two rare Civil War-era publications. The first is a 102-page excerpt from a larger work, “Sketches from the Civil War in North America,” featuring thirty etchings (measuring 12 x 9 inches) created by Dr. A. J. Volck, a Baltimore dentist of German origin. These etchings, secretly produced and privately distributed during the war’s early years, depict scenes from the Confederate Army. The excerpt’s provenance is complex, with conflicting accounts of the number of prints originally made. While some sources claim an edition of two hundred sets, the author of the excerpt states he could only locate thirty plates for reproduction, suggesting the original edition was far smaller and many prints were lost or destroyed. The author’s preface further clarifies that the artist, fearing exposure, destroyed the printing plates after a limited run of only twelve copies for personal acquaintances. The discrepancy between reported print runs highlights the rarity and clandestine nature of Volck’s work.

The second publication, “Ye Book of Copperheads” (1863), offers a contrasting perspective. This 34-page book, published in 1863, contains anti-Copperhead poems and 27 illustrations. It satirizes the Peace Democrats, a faction within the Northern Democratic Party who opposed the war and advocated for immediate peace with the Confederacy. The “Copperheads,” as they were derisively called by their Republican adversaries, represented the most outspoken segment of this anti-war movement within the North. Their belief that a full-scale war to preserve the Union was unwarranted positioned them as strong critics of the Lincoln administration’s war policies. The book’s existence demonstrates the intense political divisions and heated rhetoric characterizing the Northern United States during the Civil War.

Related products

-

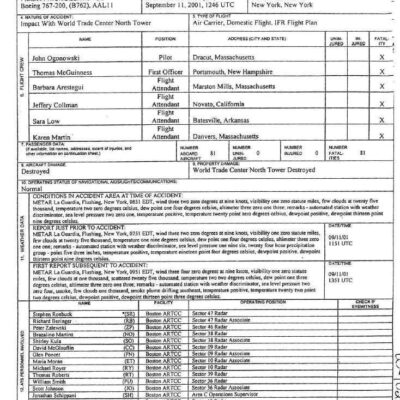

9/11 Terrorist Attacks: FAA & NTSB Documents

$19.50 Add to Cart -

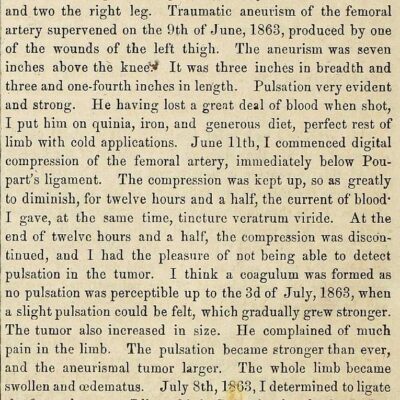

Civil War Confederate States Medical and Surgical Journal (1864 – 1865)

$19.50 Add to Cart -

Tulsa Oklahoma African American Newspaper Tulsa Star 1913-1921

$9.90 Add to Cart -

Civil War: Frank Leslie’s Weekly Illustrated Newspaper (1860-1865)

$19.50 Add to Cart