Dr. Seuss – Theodor Geisel World War II Political Cartoons

$19.50

Description

Theodor Seuss Geisel, better known as Dr. Seuss, is renowned for his beloved children’s books. However, long before he charmed generations with whimsical tales, Geisel was a prolific political cartoonist, particularly during World War II. A collection of 388 of his wartime cartoons reveals a different side of the celebrated author.

Before his literary success, Geisel honed his artistic skills in commercial illustration. Starting in 1928, he created a highly successful advertising campaign for Flit insecticide, a campaign that ran for an impressive 17 years and became a classic example of effective advertising. The distinctive style he employed in these advertisements, characterized by whimsical yet menacing creatures, foreshadowed the visual flair he would later become famous for in his children’s books. The catchy slogan, “Quick, Henry, the Flit!”, entered the American vernacular.

Throughout the 1930s, Geisel’s commercial illustration career flourished, with his artwork gracing advertisements for major corporations such as Standard Oil, General Electric, NBC, and Narragansett Brewing Company. This experience provided him with a strong foundation in visual communication and storytelling.

He transitioned into children’s literature in the late 1930s, publishing several books under the Dr. Seuss pseudonym. These early works, including “And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street,” established his unique style and writing voice.

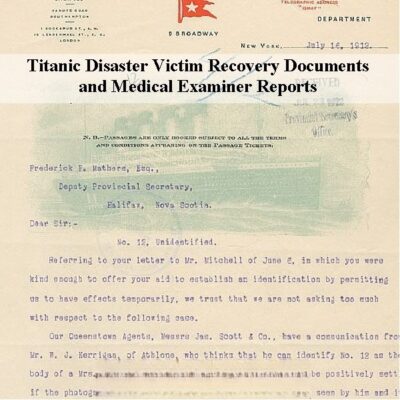

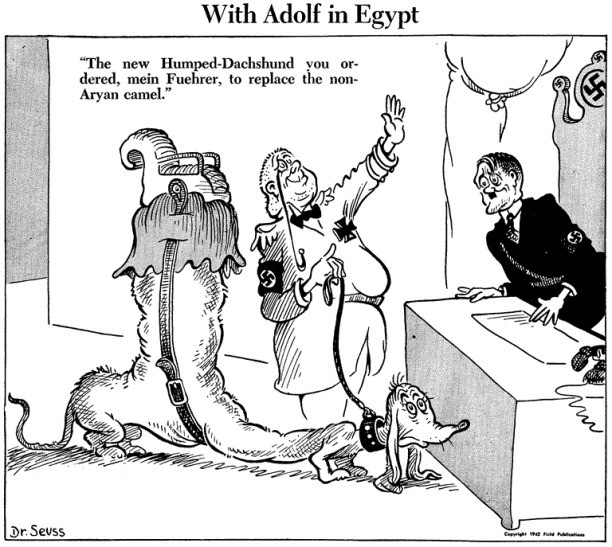

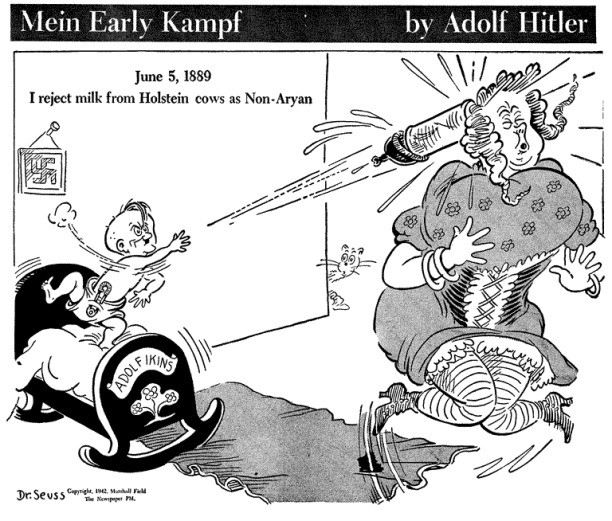

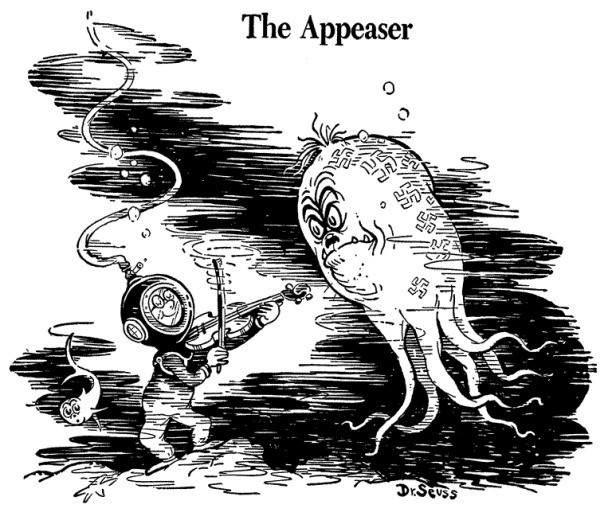

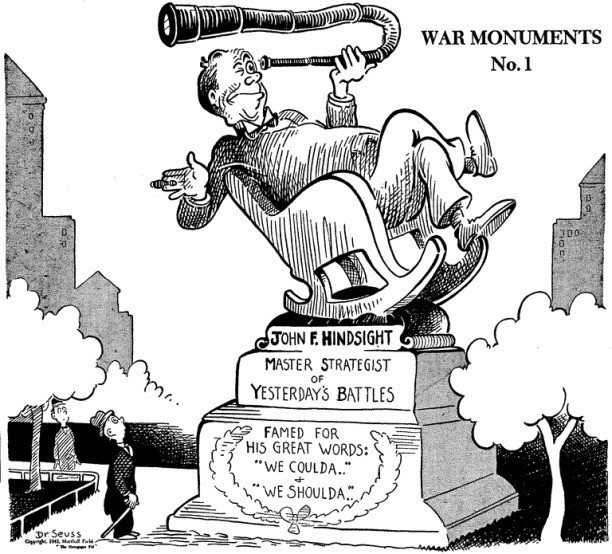

In 1941, Geisel’s talents found a new outlet: political cartooning for the New York City newspaper PM. This left-leaning, pro-New Deal, and interventionist publication provided a platform for Geisel to express his views on the escalating political climate leading up to and during the United States’ involvement in World War II. Over a two-year period, he produced almost 400 cartoons that focused heavily on the political and social issues surrounding America’s entry into the war and its subsequent participation in the European and Pacific theaters. These cartoons offer a fascinating glimpse into Geisel’s political perspectives and his artistic response to a pivotal moment in history. The distinctive style of Dr. Seuss’s wartime cartoons, characterized by both gentle humor and sharp satire, transcended the typical constraints of mainstream newspapers. These illustrations possessed a boldness rarely seen in the press of that era. During his military service in World War II, Theodor Geisel (Dr. Seuss) was described by a superior officer as a “personable zealot,” a characterization perfectly reflected in the approximately 400 political cartoons he created for PM magazine.

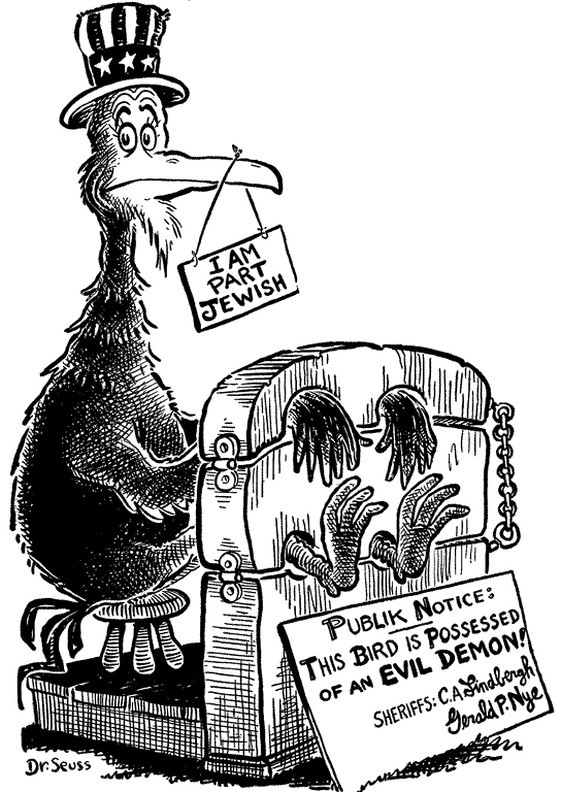

These cartoons reveal Geisel’s staunch opposition to American isolationism. He depicted the inaction towards German and Japanese expansionism as either cruel indifference, cowardly inaction, or a dangerous policy of appeasement. His drawings forcefully condemned those he believed were recklessly steering the United States towards disaster, including prominent figures such as Charles Lindbergh, Father Charles Coughlin, and others associated with the America First Committee and the German-American Bund. He didn’t pull any punches in his depictions of these individuals and groups.

One particularly striking example is the July 16, 1941, PM cartoon, “The Isolationist.” This illustration portrays the isolationist stance, particularly that championed by Charles Lindbergh, as a whale perched atop an Alpine mountain, safely removed from the turmoil of the world. The accompanying poem humorously emphasizes the whale’s self-preservation at the expense of global conflict. The poem subtly mocks Lindbergh’s detached perspective.

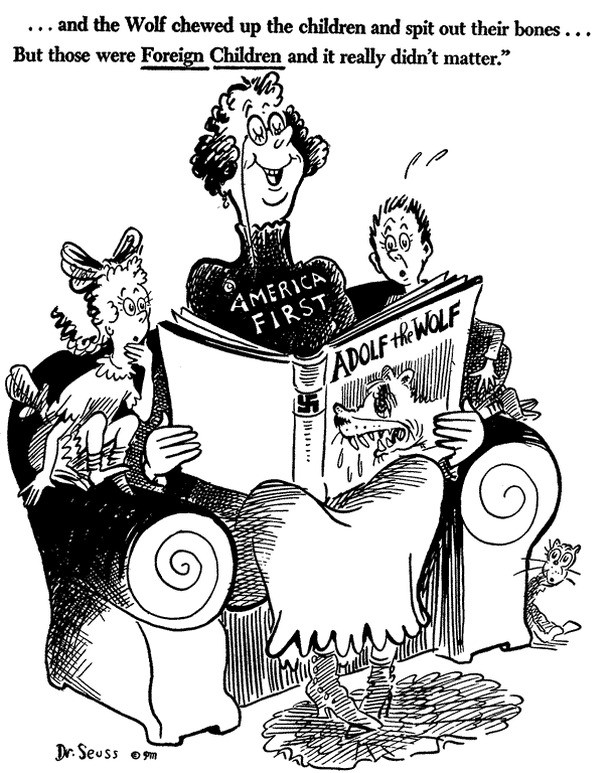

Further cartoons depicted American isolationists as callous and unconcerned with the consequences of their views. One memorable image shows a woman representing “America First” reading a gruesome story, “Adolf the Wolf,” to her children, highlighting the indifference to suffering beyond American borders. The story’s chilling climax underscores the isolationists’ apathy towards the plight of foreign victims.

While Geisel’s cartoons sharply criticized the ideology of groups like “America First,” he avoided explicitly labeling them as Nazis. However, he effectively conveyed the message that their views, regardless of their specific affiliations, posed a significant threat to the safety and well-being of the United States. The progressive stance Theodor Seuss Geisel (Dr. Seuss) took against Nazism, fascism, anti-Semitism, and the discrimination faced by African Americans will resonate positively with many. His outspoken condemnation of these injustices is widely appreciated.

Art Spiegelman, a renowned cartoonist himself, lauded Geisel’s work, highlighting its powerful and unwavering opposition to isolationism, racism, and anti-Semitism—a stark contrast to the prevailing timidity of most American publications at the time. Spiegelman emphasized the unique nature of Geisel’s cartoons, noting that they were practically the only ones outside of communist and Black newspapers that openly criticized the military’s discriminatory Jim Crow policies and Charles Lindbergh’s anti-Semitic views. Geisel himself attributed his activism to the rise of Hitler, stating that his work was fundamentally opposed to oppression, a sentiment he found personally appealing. Spiegelman characterizes Geisel as more of a humanist than a rigid ideologue, suggesting a pragmatic, rather than doctrinaire, approach to social justice. He praises the passionate and genuine anger fueling Geisel’s political cartoons, recognizing their inherent humor as a charming characteristic.

However, a significant shortcoming in Geisel’s work lies in his stereotypical depictions of Japanese and Japanese-Americans. Many find these cartoons, created months before the attack on Pearl Harbor, deeply offensive and racially prejudiced by modern standards. The problematic nature of these earlier works casts a shadow on his later, more progressive cartoons. A deeply unsettling cartoon, published in the PM newspaper on February 13, 1942, and titled “Waiting for the signal from home,” depicted a vast, unsettlingly uniform line of Japanese-Americans stretching along the entire West Coast. This visual representation, extending from Washington to California, portrayed them waiting to collect explosives from a building labeled “Honorable 5th Column.” The image powerfully reflected the widespread, and ultimately unfounded, suspicion among many Americans that individuals of Japanese descent were disloyal and posed a significant internal threat. This pervasive distrust stemmed from a belief that Japanese-Americans, if commanded by the Emperor, would act as saboteurs, causing widespread destruction. This prejudice, fueled by the trauma of the Pearl Harbor attack on December 7, 1941, directly contributed to the unjust internment of Japanese-Americans in concentration camps.

Another controversial cartoon by the same artist, published in PM on January 13, 1942, depicted John Haynes Holmes, a well-known pacifist and Unitarian minister, alongside a Japanese soldier wielding a knife and a severed head. This image, which sparked a significant public outcry and a deluge of supportive letters for Holmes, revealed the prevailing anti-Japanese sentiment. The artist’s subsequent editorial response, appearing in PM on January 21, 1942, was a stark and unapologetic defense of his work. He cynically acknowledged the ideals of peace and brotherhood but argued that such sentiments were inappropriate during wartime. The editorial bluntly stated that the imperative to win the war necessitated the killing of Japanese people, regardless of the impact on pacifists’ sensibilities; reconciliation, he suggested, could be considered only after victory. This response further underscores the intense nationalistic fervor and dehumanization of the Japanese enemy prevalent during that period. Some believe Theodor Geisel, better known as Dr. Seuss, showed remorse for his wartime actions later in his life. This belief stems partly from his post-war trip to Japan. The widespread theory is that his 1954 book, “Horton Hears a Who!”, dedicated to a Japanese professor he befriended during his visit, uses the Whos as a metaphorical representation of the Japanese people. Richard Minear, in his 1999 book, “Dr. Seuss Goes to War,” even suggests the story serves as an allegory for America’s post-war occupation of Japan.

Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, which ended the national debate over isolationism, Geisel’s illustrations shifted their focus. He primarily created artwork to boost public morale and encourage the purchase of war bonds. However, his most intense criticism was consistently directed at Adolf Hitler, who featured prominently in a staggering 108 of Geisel’s World War II political cartoons.

The vast range of themes explored in Geisel’s political cartoons, produced between January 1941 and January 1943, encompassed a wide spectrum of contemporary issues. These included the “America First” movement, the Anti-Comintern Pact, anti-Semitism, appeasement policies, bureaucratic inefficiencies, public carelessness, the House Un-American Activities Committee, communism, complacency, the actions of Congress, defeatism, national disunity, domestic security concerns, elections, foreign aid, the German invasion of the Soviet Union, the contrast between “good news” and “bad news,” public inactivity, inflation, isolationism, Japan’s fuel imports, the role of journalism, the impact of labor on war production, the Lend-Lease Act, military matters, the Neutrality Acts, the sinking of the Normandie, overconfidence, the patriotism of Japanese-Americans, peace negotiations, political corruption, production efforts, propaganda, racism, rationing and recycling, recruitment drives, the Republican Party, the sale of savings bonds and stamps, the “Society of Red Tape Cutters,” Tammany Hall, taxation, the United Nations, war bonds, the overall war effort, war industries, and war profiteering.

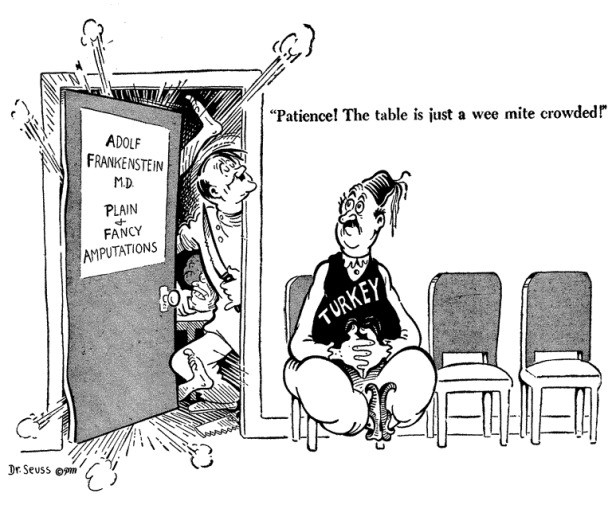

His cartoons also depicted many prominent figures of the era, including Franklin D. Roosevelt, Harry Truman, Adolf Hitler, Joseph Stalin, Benito Mussolini, Joseph Goebbels, and Hideki Togo. The list encompasses a diverse range of prominent figures from the mid-20th century, including political leaders, military strategists, journalists, and commentators. This group represents a cross-section of individuals who significantly shaped the events and public discourse of their time, particularly during World War II. Names like Theodore Bilbo, a controversial US Senator, and Charles E. Coughlin, a highly influential Catholic priest and radio personality, highlight the political polarization of the era. Military figures such as Douglas MacArthur and Erwin Rommel, representing opposing sides in the war, are also included, alongside key figures in the Allied and Axis governments. Journalists and commentators such as Elmer Davis and Eleanor Roosevelt, who played vital roles in shaping public opinion, are also present. This eclectic mix underscores the broad scope of Dr. Seuss’s observations and commentary during this period.

In 1942, Dr. Seuss began contributing to the war effort by creating propaganda posters for government agencies. This marked a shift in his career, moving from his established work in advertising and children’s literature to direct involvement in the national war campaign.

Starting in 1943, Dr. Seuss’s contributions expanded significantly when he joined the US Army as a captain. He served as the head of the animation department within the Army Air Forces, playing a critical role in producing training films. His work included the influential Private Snafu series, aimed at educating soldiers, and post-war films designed to prepare troops for occupation duties in Japan and Germany. These films demonstrate his commitment to the war effort and his ability to communicate complex information effectively through animation.

Following the war, Dr. Seuss returned to his successful career in children’s literature. This post-war period witnessed the creation of many of his most beloved and enduring works. The list of titles, from Horton Hears a Who! to The Butter Battle Book, represents a significant contribution to American children’s literature, leaving an indelible mark on generations of readers.

Many of the whimsical characters and themes found in these iconic books have their roots in Dr. Seuss’s earlier political cartoons. These cartoons, often satirical in nature, provided a commentary on the political climate of the time, foreshadowing the creative themes and characters that would later appear in his children’s books.

The accompanying glossary helps to contextualize the cartoons by identifying the individuals depicted or referenced. Many of these individuals are now largely forgotten, highlighting the ephemeral nature of fame and the passage of time. Their prominence during the mid-20th century contrasts with their relative obscurity today, illustrating the shifting sands of historical memory. The provided text gives brief biographies of several significant figures, highlighting their political stances and actions, particularly concerning World War II. Let’s examine each individual in more detail:

Theodore Bilbo, a Mississippi Democrat, served as both governor and US Senator. His political career was notably marked by his skillful use of the filibuster, a tactic in the Senate to delay or block legislation, a skill Geisel’s caricature likely alluded to. This suggests Bilbo’s image was associated with obstructionism.

Charles Coughlin, a powerful Catholic priest, used his popular radio broadcasts to disseminate controversial views. His pronouncements included anti-Semitic rhetoric and expressions of sympathy for the actions of Hitler and Mussolini, revealing a disturbing alignment with fascist ideologies. This illustrates the significant influence of media personalities and the dangers of unchecked political speech.

Stafford Cripps, a British diplomat, played a crucial role in securing an alliance with the Soviet Union during a critical period. His 1940 mission to Moscow resulted in a clandestine agreement for Soviet entry into the war against Nazi Germany, despite the prior Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact between the Soviets and the Nazis. This underscores the complex and shifting geopolitical alliances of the time.

Robert R. McCormick, the influential publisher of the Chicago Tribune, was a staunch non-interventionist. He actively opposed American involvement in World War II and resisted the expansion of federal power under the New Deal. His newspaper’s editorial stance significantly shaped public opinion and contributed to the isolationist sentiment prevalent in the United States.

Hamilton Fish, a New York congressman, was a prominent isolationist. His views, characterized as “the Nation’s No. 1 isolationist” by Time magazine, evolved from initially sympathizing with Germany’s claims to later becoming embroiled in the activities of a Nazi agent. This highlights the spectrum of isolationist sentiment and the potential for individuals to become entangled in controversial political activities.

Norman Thomas, a prominent socialist and pacifist minister, ran for president multiple times. He initially led efforts to keep the US out of the war, forming the “Keep America Out of War Congress.” However, the attack on Pearl Harbor prompted a shift in his stance, demonstrating the impact of major events on even deeply held beliefs. His evolution reveals the internal conflicts faced by many pacifists during the war.

Dr. Seuss: War, Politics, and Children’s Literature

This timeline focuses on the period from the late 1930s to the post-World War II years, primarily covering Theodor Geisel’s (Dr. Seuss) career and the events that influenced his political cartoons.

Late 1920s – 1930s:

- 1928: Theodor Geisel starts illustrating advertisements for Flit, a DDT-based insecticide. The campaign runs for 17 years and becomes a massive success, making the tagline “Quick, Henry, the Flit!” a national catchphrase.

- 1930s: Geisel continues as a successful commercial illustrator, working for prominent clients like Standard Oil, General Electric, NBC, and Narragansett Brewing Company.

- Late 1930s: Geisel begins writing and illustrating children’s literature, publishing under the pen name Dr. Seuss. Key works from this period include:

- And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street (1937)

- The 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins (1938)

- The King’s Stilts (1939)

- The Seven Lady Godivas (1939)

- Horton Hatches the Egg (1940)

1940s: World War II Era

- 1941: Geisel joins the politically left-leaning, interventionist New York newspaper PM as a political cartoonist. His work focuses on American isolationism and the rising threat of Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan.

- Geisel’s cartoons frequently criticize prominent isolationist figures like Charles Lindbergh, Father Charles Coughlin, and members of the America First Committee.

- He also targets individuals seen as appeasing or enabling fascist aggression, including Gerald Nye, Burton Wheeler, and Hamilton Fish.

- December 7, 1941: Japan attacks Pearl Harbor, effectively ending the debate over American isolationism and propelling the United States into World War II.

- 1942: Geisel’s focus shifts from criticizing isolationism to boosting morale and promoting the war effort, including the sale of war bonds. He continues to satirize Hitler and other Axis leaders.

- February 13, 1942: PM publishes Geisel’s controversial cartoon depicting Japanese-Americans on the West Coast waiting for a signal to sabotage the United States, reflecting the prevalent wartime prejudice against Japanese-Americans.

- Geisel also draws posters for the Treasury Department and the War Production Board.

- 1943: Geisel enlists in the U.S. Army as a captain and is assigned to the First Motion Picture Unit of the Army Air Forces. He leads the Animation Department and works on training films, including the “Private Snafu” series.

- 1945: Geisel contributes to the production of postwar training films, Our Job in Japan and Your Job in Germany.

Post-War Years

- Post-war: Geisel returns to children’s literature and achieves his greatest success with classic Dr. Seuss books:

- Horton Hears a Who! (1954) – potentially an allegory for the American occupation of Japan and the importance of recognizing even the smallest voices.

- The Cat in the Hat (1957)

- How the Grinch Stole Christmas! (1957)

- Yertle the Turtle and Other Stories (1958)

- One Fish Two Fish Red Fish Blue Fish (1959)

- Green Eggs and Ham (1960)

- The Sneetches and Other Stories (1961)

- The Lorax (1971)

- The Butter Battle Book (1984)

Cast of Characters

Theodor Seuss Geisel (Dr. Seuss):

- A talented artist and writer, known for his whimsical children’s books and political cartoons.

- Worked as a commercial illustrator before achieving literary success as Dr. Seuss.

- Became a vocal critic of isolationism and fascism through his powerful cartoons for PM.

- Served in the U.S. Army during World War II, contributing to training films.

- Achieved international fame and critical acclaim for his imaginative and thought-provoking Dr. Seuss books.

Franklin D. Roosevelt:

- President of the United States during the Great Depression and most of World War II.

- Implemented the New Deal, a series of programs designed to alleviate economic hardship.

- Initially advocated for American neutrality but gradually steered the nation toward supporting the Allies.

- Led the country through World War II, playing a crucial role in Allied victory.

Adolf Hitler:

- Dictator of Nazi Germany, responsible for World War II and the Holocaust.

- Promoted extreme nationalism, anti-Semitism, and a racist ideology.

- Led Germany into war, conquering much of Europe before being defeated by the Allied forces.

- A frequent target of Geisel’s satirical attacks, representing the evils of fascism and totalitarian aggression.

Charles Lindbergh:

- Famous aviator known for his solo transatlantic flight.

- Became a prominent voice in the America First Committee, advocating for American isolationism and neutrality.

- Criticized for his pro-German leanings and anti-Semitic views.

- A recurring figure in Geisel’s cartoons, representing the dangers of isolationism and appeasement.

Father Charles Coughlin:

- A controversial Roman Catholic priest who hosted a popular radio show.

- Known for his anti-Semitic and pro-fascist rhetoric, supporting some of Hitler and Mussolini’s actions.

- Drew criticism for his extremist views and divisive language.

- A subject of Geisel’s cartoons, highlighting the dangers of hate speech and intolerance.

Other Notable Figures:

- Joseph Stalin: Leader of the Soviet Union during World War II.

- Benito Mussolini: Fascist dictator of Italy.

- Hideki Tojo: Prime Minister of Japan during World War II.

- Gerald Nye, Burton Wheeler, Hamilton Fish: Prominent American isolationist politicians.

- John Haynes Holmes: Pacifist minister criticized by Geisel for his anti-war stance.

- Theodore Bilbo, Stafford Cripps, Robert R. McCormick, Norman Thomas: Other political and social figures featured or mentioned in Geisel’s cartoons, representing various viewpoints and ideologies of the time.