African American Slave Testimonies and Photographs

$19.50

Description

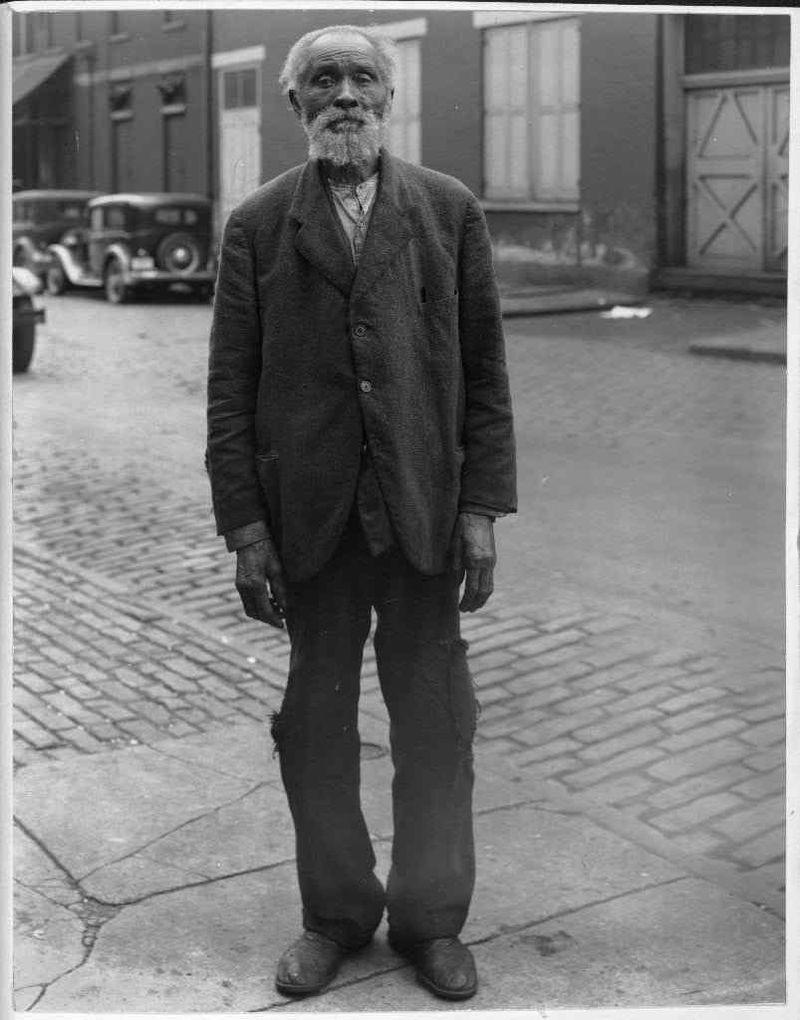

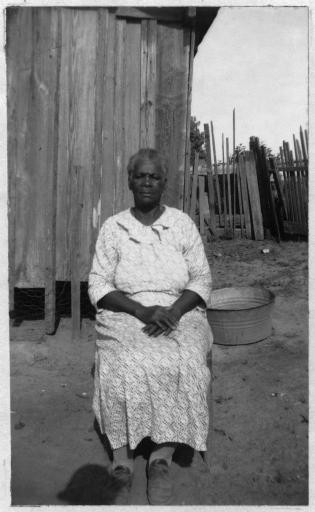

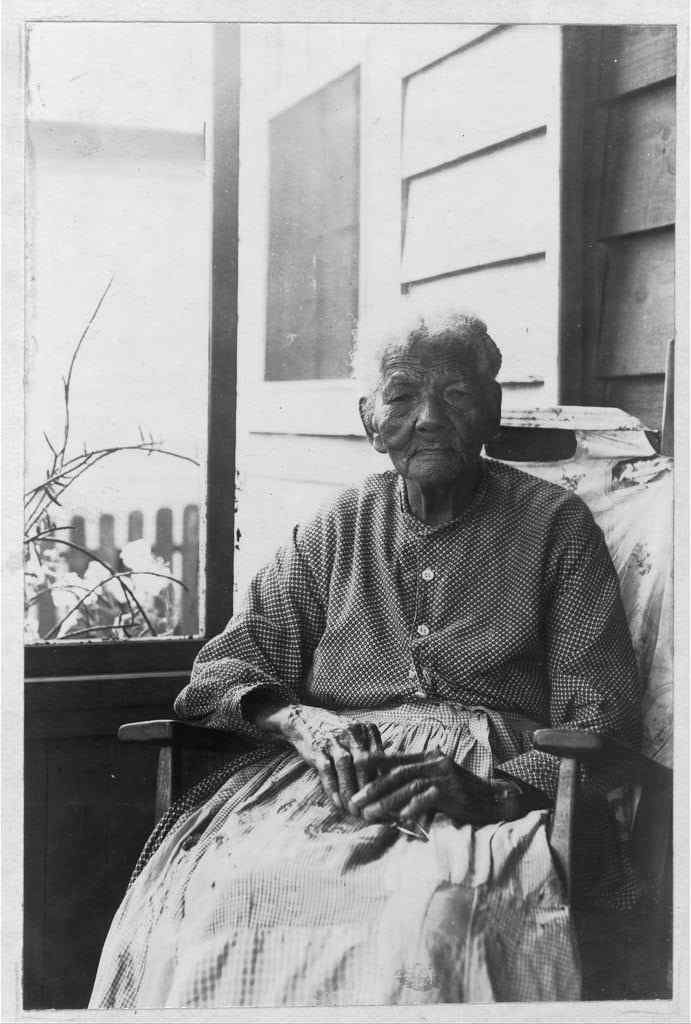

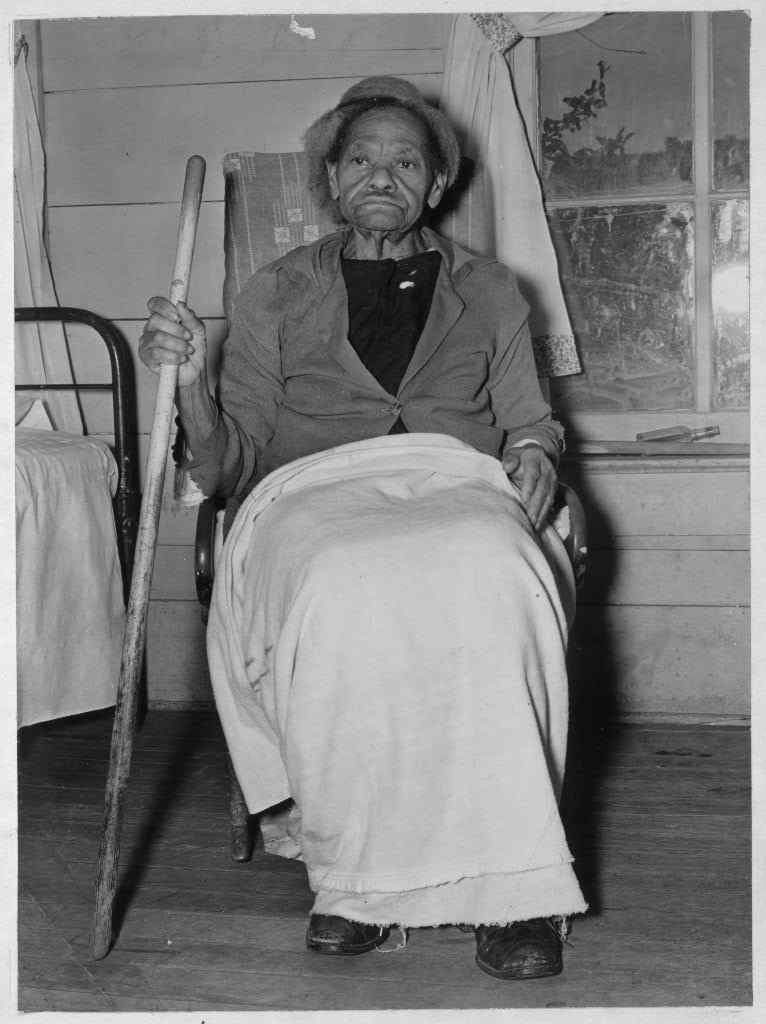

This collection comprises a vast archive of African American history, encompassing nearly 10,000 pages of firsthand accounts from former slaves and over 400 accompanying photographs. These invaluable primary source documents offer unparalleled insight into the lived experiences of individuals who endured the brutal institution of slavery in the United States.

The core of this collection originates from the Federal Writers’ Project (FWP), a New Deal initiative launched during the Great Depression. Between 1936 and 1938, unemployed writers across seventeen states undertook the monumental task of recording oral histories, capturing the life stories of ordinary Americans. Initially, the focus on former slaves was limited to four Southern states; however, due to the compelling nature of the initial material, the project expanded nationwide.

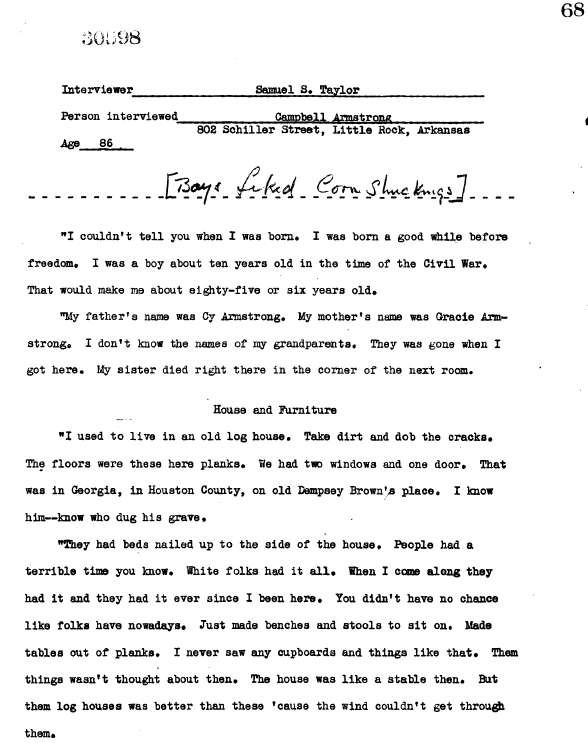

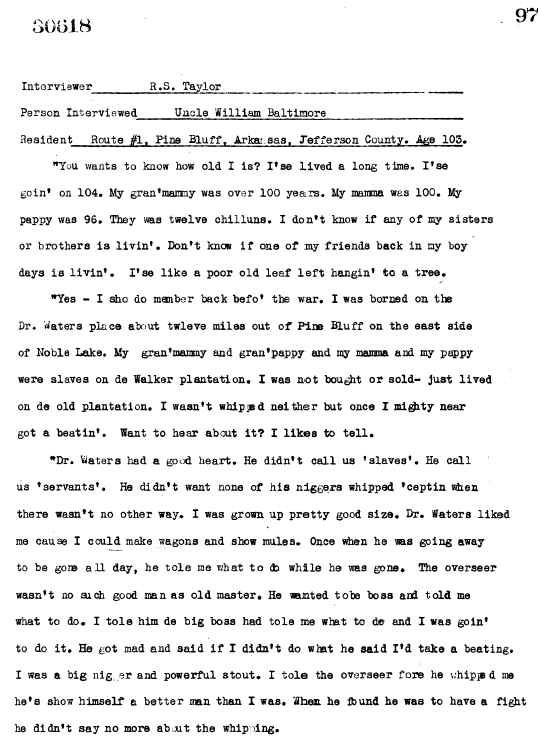

The FWP’s initiative to document the experiences of former slaves was spearheaded by John A. Lomax, who recognized the crucial historical significance of these narratives. He ensured that the project expanded to include interviews with ex-slaves across the participating states. To ensure accuracy and authenticity, field workers received specific guidelines on interviewing techniques, including instructions on how to accurately transcribe the unique dialects of their interviewees. Careful attention was paid to detail, with many interviewees visited multiple times to gather as complete a recollection as possible.

The resulting narratives were then meticulously edited at the state level before being sent to Washington D.C. for compilation and preservation. The accompanying administrative records provide further context, detailing the instructions given to field workers and the concerns of state FWP directors, offering a rich understanding of the project’s logistical and intellectual framework. The final product, completed in 1941, became the seventeen-volume “Slave Narratives: A Folk History of Slavery in the United States from Interviews with Former Slaves,” a cornerstone of American historical scholarship. The vast collection of American slave narratives offers an unparalleled and exceptionally rich depiction of the enslaved population’s experiences. This collection’s significance is underscored by historian David Brion Davis, who, in his work “Slavery and the Post-World War II Historians,” emphasizes its unparalleled scale compared to similar collections from other nations with a history of slavery. The sheer volume of documented testimonies is remarkable. Beyond the sheer quantity, however, the collection’s true power lies in the diversity of its contributors. While not a statistically perfect representation of the entire enslaved population, the narratives encompass a strikingly broad range of individuals.

The individuals who shared their stories spanned a wide age range at the time of emancipation in 1865, from infancy to middle age, resulting in a majority being octogenarians or older during the interview process. The overwhelming majority had lived through slavery in the Confederate states and continued to reside there. The narratives represent the full spectrum of labor performed by enslaved people. Furthermore, the size and nature of the slaveholding units varied greatly among the interviewees’ experiences, encompassing everything from massive plantations with over a thousand slaves to situations where the individual was the sole enslaved person owned by a single person. The accounts detail a wide spectrum of treatment, ranging from brutal and exploitative conditions to surprisingly kind and personal relationships with slaveholders. Essentially, the collection provides a comprehensive representation of the enslaved population, with the notable exception of older slaves who had passed away before the interviews took place. The diversity of experiences captured within this collection makes it a uniquely valuable historical resource.

This extensive list of topics delves deeply into the multifaceted experiences of enslaved people in the American South, covering a broad spectrum of their lives, from the brutal realities of their enslavement to their resilience and pursuit of freedom. The subjects range from the oppressive systems of slave ownership and control—including the roles of slave masters and overseers, the pervasive violence of whippings, and the constant threat of separation from family—to the intimate details of daily life: marriages, childbearing and rearing, diet, health, and religious and social practices. The list also touches upon the enslaved people’s cultural expressions, encompassing folklore, superstitions, and limited access to education. Furthermore, it explores the realities of escape attempts, the vigilance of patrollers and jayhawkers, the complex dynamics of relationships between slave owners and enslaved individuals, and the involvement of Black people in the Civil War, both within the Confederate and Union armies. The post-slavery era is also addressed, encompassing the rise of the Ku Klux Klan and the difficult transition to freedom.

The lives sampled include:

John W. Fields’ account, from an 89-year-old formerly enslaved person, highlights the strong desire among enslaved people for literacy, despite the severe legal penalties for both enslaved individuals and white people who dared to teach them. He describes the harsh treatment meted out by plantation owners to those caught learning to read and write, emphasizing the significant legal repercussions for white individuals who aided in this endeavor. His testimony reveals the limited worldview imposed upon enslaved people, confined to the plantation economy and unaware of the broader marketplace. He underscores the crucial role of ignorance in maintaining the system of slavery, acknowledging the risk of escape but highlighting the daunting uncertainties that lay ahead for those who fled. The severe punishments faced by runaway slaves are also emphasized.

Tempie Cummins’ testimony, while lacking a specific age, is presented in transcribed form, suggesting potential challenges in accurately representing her dialect and pronunciation. The absence of specifics necessitates further investigation of the content of her account. Despite attempts by white children to educate her, Charity Anderson’s education was limited due to her constant workload. Her mother, also a hardworking domestic servant, possessed a remarkable resourcefulness. She secretly eavesdropped on conversations between her enslavers, learning about the emancipation proclamation before it was officially announced to the enslaved people. Upon hearing her master’s intention to delay informing the slaves of their freedom, Charity’s mother took decisive action. She celebrated her newfound liberty with a jubilant display of freedom, a symbolic act of defiance. Then, defying her master’s authority, she informed the other enslaved people of their freedom, leading to a collective work stoppage. Her escape was daring and dramatic; she fled to a secluded ravine, bringing her child to safety, narrowly avoiding her master’s gunfire.

Charity Anderson, at 101 years old, shared her life story near Mobile, Alabama. Born at Belle’s Landing in Monroe County, Alabama, she served as a domestic slave on a wood yard that supplied riverboats. While her master exhibited kindness towards his enslaved workers, Anderson’s recollections also include witnessing brutal acts of violence against other slaves, highlighting the stark contrast between relative leniency and extreme cruelty within the system of slavery. Mary Reynolds, a centenarian at the time of her interview, experienced the harsh realities of slavery from her birth in Black River, Louisiana. This remarkable woman, born into bondage, lived through the cruelty of a slaveholding physician and planter who prioritized profit over human life. He regularly exchanged his aging slaves for younger, more robust individuals, demonstrating a callous disregard for human worth. Reynolds endured unimaginable suffering, recalling brutal physical punishments and the agonizing pain of working in freezing conditions that caused her hands to bleed. The complexities of her master’s life were further revealed by his extramarital affairs with an enslaved woman of mixed race, leading to conflict with his wife who threatened separation. Following emancipation, Reynolds relocated to Texas, where she spent the remainder of her days.

Clayton Holbert, at the age of 86, shared his memories of growing up enslaved in Linn County, Tennessee. His enslaver, Pleasant Holbert, commanded a large plantation of approximately one hundred enslaved people. These individuals were responsible for cultivating various crops, including corn, barley, and cotton. The plantation operated as a self-sustaining entity, with enslaved people demonstrating remarkable resourcefulness by producing their own clothing, processing their own meat, and even making maple sugar. Tragically, Holbert’s family experienced the devastating consequences of the slave trade firsthand, as both his mother and grandmother, who had briefly been granted freedom, were abducted and forced back into slavery. In a stark contrast to the oppression they endured, Holbert’s father, brother, and uncle bravely joined the Union Army during the Civil War, fighting for their freedom and the liberation of others.

Walter Calloway, whose life began in Richmond, Virginia in 1848, recounted his experiences as an enslaved person. He and his family were purchased by John Calloway, who owned a large plantation near Montgomery, Alabama. From a young age, Calloway was subjected to backbreaking labor, performing the work of a grown man by the age of ten. The brutality of the system is vividly illustrated by his account of witnessing a young girl, just thirteen years old, being whipped mercilessly, nearly to death, by an overseer who used an enslaved person to carry out the violence.

Calloway’s narrative also includes details about his religious practices, attending services in a makeshift brush arbor, and the profound impact of the Civil War, culminating in the chaotic ransacking of the plantation by federal troops at the war’s conclusion. Emma Crockett, nearing eighty years of age, was the offspring of Cassie Hawkins and Alfred Jolly, yet lived her life as an enslaved person under the ownership of Bill and Betty Hawkins. Following the abolition of slavery, she acquired a rudimentary understanding of printed text, but remained unable to decipher handwritten script. A devout member of the New Prophet Church, she demonstrated her faith by singing a beloved hymn for her interviewer, despite suffering from a headache that day.

Lucinda Davis, a resident of Tulsa, Oklahoma, had uncertain origins, her birthplace remaining unknown to her. However, she successfully located and reunited with her parents after the Civil War concluded. She had been held in bondage by Tuskaya-hiniha, a Creek Indian, and his Caucasian spouse, Nancy Lott. Living on a farm near Honey Springs, approximately twenty-five miles south of Fort Gibson, she was one of roughly ten enslaved individuals. Creek was the primary language spoken in her household, and she retains vivid memories of Creek funeral rites, dances, and culinary traditions. The chaos of the Civil War led to the escape of her fellow enslaved people, leaving her alone—too young to flee independently—in the service of her owners.

Tempe Herndon Durham, at the remarkable age of 103, spent her formative years on a substantial plantation situated in Chatham County, North Carolina, to the west of Raleigh. This plantation, under the control of George and Betsy Herndon, produced a variety of crops including corn, wheat, cotton, and tobacco. Durham provides detailed accounts of the textile production processes undertaken by the enslaved women, including spinning, weaving, and dyeing of cloth. She exchanged marriage vows with Exter Durham on the veranda of her enslaver’s residence; a lavish wedding celebration was thrown by her master, though Exter was compelled to return to his own enslaver’s plantation the following day. After the war’s end, the couple resided on the Herndon property as tenants, diligently saving until they could afford to purchase their own farm.

Joseph Holmes, a Virginia native who reached the age of 81, began his life near Danville in Henry County. His parents were Eliza Rowlets and Joseph Holmes. He later relocated from Virginia to Georgia, eventually settling in Mobile, Alabama, where he shared his life story. He remembered his enslaver as a woman who treated her enslaved people relatively well, prioritizing their health and well-being due to the financial implications of mistreatment in the slave trade. The concept of his freedom, granted by his enslaver, wasn’t immediately clear to Holmes; it took him a considerable amount of time—a decade or more—to fully grasp its significance.

Ben Horry, a resident of Murrells Inlet, South Carolina, was 89 years old at the time of his interview. Living a coastal life about ten miles south of Myrtle Beach, he spoke in the distinctive dialect of the Lowcountry region. His account included details about his work as a boatman, his experiences during the federal occupation of the South during the Civil War, the disciplinary actions his father faced for excessive drinking, and the typical foods consumed in that area.

Richard Toler, born near Lynchburg in Campbell County, Virginia, was the offspring of George Washington Toler and Lucy Toler, and he was enslaved by Henry Toler. During his childhood, he performed farm chores, tending livestock on his master’s extensive 500-acre property. His responsibilities later expanded to include fieldwork. He acquired blacksmithing skills while enslaved and continued this trade for 36 years after emancipation, earning his livelihood as a skilled smith. Post-Civil War, he developed a passion for music, purchasing a fiddle and becoming a proficient musician, performing at both white social gatherings and informal community events.

His recollections included medical practices during slavery, along with descriptions of the food and clothing provided, and he also recounted the horrific physical abuse inflicted upon young girls by his master’s sons. This digital collection provides comprehensive text accessibility. Each document’s image has been processed to extract all discernible text. This extracted text is then compiled into a searchable transcript, forming a readily available finding aid. In essence, the system converts the visual information present in the images into a machine-readable format. This allows users to easily search for specific words or phrases. The search functionality isn’t limited to individual documents; it encompasses the entire collection. This means a single search query can yield results from any document within the archive, significantly enhancing the discoverability of information contained within the graphic images. The creation of these text transcripts effectively transforms a collection of visual documents into a fully searchable textual database.

Slave Narratives: A Folk History of Slavery in the United States

Please note that the provided source focuses on the structure and content of a collection of slave narratives and doesn’t provide specific events to build a detailed timeline. However, we can create a general timeline of the period and highlight the events mentioned in the source description:

Timeline

1836-1865: Period of Slavery in the United States covered by the testimonies.

- Specific events mentioned within this period from the source material include:Individual accounts of slave life: births, daily work, family life, religious practices, punishments, and escapes.

- Accounts of slave sales and family separations.

- The Civil War (1861-1865).

- Union soldiers entering the South.

- Emancipation Proclamation (1863).

1865: The 13th Amendment abolishes slavery in the United States.

Post-1865: Reconstruction Era.

- Specific events mentioned within this period from the source material include:Transition from slavery to freedom.

- Experiences with the Ku Klux Klan.

- Black individuals learning to read and write.

- Economic struggles and sharecropping.

1936-1938: Federal Writers’ Project interviews former slaves as part of the Works Progress Administration (WPA). This is when the specific testimonies described in the source were collected.

1941: The seventeen-volume “Slave Narratives: A Folk History of Slavery in the United States from Interviews with Former Slaves” is assembled and microfilmed.

Cast of Characters

- John A. Lomax: National Advisor on Folklore and Folkways for the Federal Writers’ Project. Instrumental in directing the project to collect narratives from former slaves.

- Former Slaves: The primary focus of the source. Over 2,300 individuals across 17 states were interviewed, providing firsthand accounts of their experiences under slavery and during the transition to freedom.

- Key Individuals Mentioned in Source Examples:

- Charity Anderson: (Approx. 1835 – Unknown) Born in Alabama, she lived to be over 100 years old. Anderson was a house slave and recounted both kind treatment and witnessing severe punishments of other slaves.

- Mary Reynolds: (Approx. 1830 – Unknown) Born into slavery in Louisiana, she lived to be over 100 years old and was blind when interviewed. Reynolds experienced her master trading older slaves for younger ones and endured brutal conditions.

- Clayton Holbert: (Approx. 1850 – Unknown) Born in Tennessee, he lived on a large, self-sufficient plantation. Holbert’s family members were recaptured after being granted freedom.

- Walter Calloway: (b. 1848) Born in Virginia and sold to a plantation in Alabama, he worked as a child laborer and witnessed harsh punishments.

- Emma Crockett: (Approx. 1857 – Unknown) Remembered struggling to learn to read and write after emancipation.

- Lucinda Davis: (Birthplace unknown) Lived as a slave in a Creek Indian household, experiencing a distinct cultural environment.

- Tempe Herndon Durham: (Approx. 1833- Unknown) Lived on a North Carolina plantation and provided detailed accounts of textile production.

- Joseph Holmes: (Approx. 1855 – Unknown) Born in Virginia and eventually moved to Alabama, he noted his mistress’s focus on keeping slaves healthy for sale.

- Ben Horry: (Approx. 1847 – Unknown) Lived in coastal South Carolina, working as a boatman.

- Richard Toler: (Birth year unknown) Born in Virginia, he learned blacksmithing and became a musician after emancipation.

- Slave Owners: The source mentions various slave owners, including those who were considered relatively kind and others known for their cruelty. Specific names (other than those listed above in individual cases) are not given in the excerpt.

- Overseers: Individuals who directly managed the labor of slaves on plantations. The source mentions overseers and their role in meting out punishments.

- “Jayhawkers”: This term generally refers to anti-slavery guerrilla fighters, particularly those operating in Kansas and Missouri during the Bleeding Kansas period and the Civil War. It’s unclear from the source how they specifically interacted with the slaves interviewed.

- Ku Klux Klan Members: The source indicates that some former slaves recounted their experiences with the KKK during the Reconstruction era.

This information forms a basic framework. A more detailed timeline and character list would require analyzing the full content of the “African-American Slave Testimonies and Photographs” collection.

Related products

-

Titanic Disaster British National Archives Documents

$19.50 Add to Cart -

Journal of the Congress of the Confederate States of America 1861-1865

$19.50 Add to Cart -

Titanic Disaster Victim Recovery and Medical Examiner Records

$19.50 Add to Cart -

Audio Recordings of Formerly Enslaved African Americans

$19.50 Add to Cart