Abraham Lincoln’s Telegrapher David Homer Bates: Papers, Diary, and Books

$19.50

Description

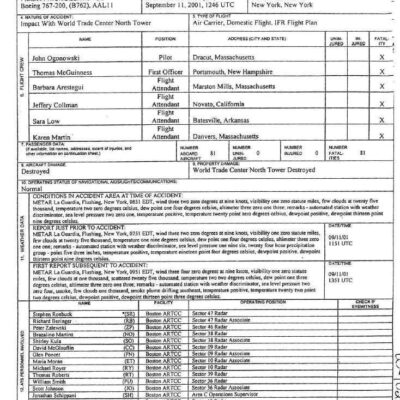

The extensive David Homer Bates collection, housed within the Library of Congress’s Alfred Whital Stern Collection of Lincolniana, offers a remarkable glimpse into the Civil War era through the eyes of a key figure in military communication. This 1,880-page archive comprises a wealth of primary source materials, including Bates’ personal correspondence, detailed diary entries, and journals, alongside historical documents, photographs, newspaper clippings, printed materials, and even drafts and annotated proof sheets of his own publications.

David Homer Bates, a prominent figure who served as a military telegrapher, author, and later vice president of Western Union, played a pivotal role in the Union war effort. His career spanned from 1861 to 1866, during which he managed and operated the crucial cipher system within the War Department’s telegraph office. His firsthand accounts are preserved in two books he authored: “Lincoln in the Telegraph Office” (1907) and “Lincoln Stories Told by Him in the Military Office in the War Department During the Civil War” (1926).

The collection’s significance extends beyond Bates’ personal experiences. It contains original documents penned by President Abraham Lincoln himself, providing invaluable insights into his thoughts and actions. A meticulously kept daily journal chronicling the unfolding events of the Civil War is a particularly noteworthy item. Furthermore, the collection includes correspondence from prominent figures on both sides of the conflict, including Confederate generals Robert E. Lee, James Lawson Kemper, Edmund Kirby Smith, Richard Stoddert Ewell, and even Confederate President Jefferson Davis. These letters offer a multi-faceted perspective on the war.

The collection also sheds light on the crucial role of the United States Military Telegraph Corps, established in 1861. Bates was among a group of skilled telegraphists who transitioned from the Pennsylvania Railroad to form the core of this vital organization. The Corps rapidly expanded to over 1,500 members, constructing and maintaining an impressive network of over 15,000 miles of telegraph lines across the nation, facilitating rapid communication during the war.

The Corps employed civilian operators, but supervisory personnel held military commissions within the Quartermaster Department to manage finances and resources. The involvement of Anson Stager, a Western Union executive, as the Corps’ general manager highlights the close collaboration between the military and commercial telegraphic sectors. President Lincoln’s seizure of the nation’s commercial telegraph lines in February 1862 further solidified this partnership, making them readily available for military use through Western Union.

In the spring of 1862, Secretary of War Stanton implemented a policy consolidating all military telegraphic communications under a single roof. This central telegraph office was established in a repurposed building—the War Department’s former library—conveniently located adjacent to Stanton’s own office.

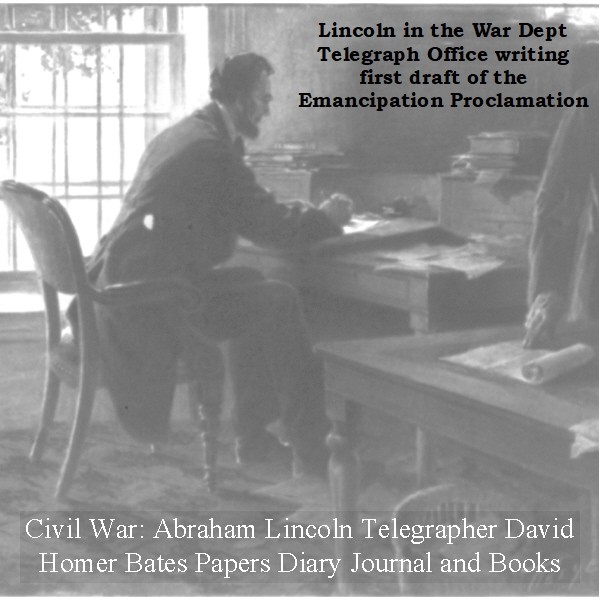

President Lincoln frequently utilized this newly centralized telegraph office for sending and receiving messages. His trips to the office were often solitary affairs, involving a short walk from the White House. These visits provided a welcome respite for the President, offering a much-needed break from the constant pressures and demands of his wartime presidency. The relative quiet of the telegraph office allowed for moments of contemplation and uninterrupted thought. Significantly, it was within these walls that Lincoln composed the initial draft of the Emancipation Proclamation.

According to David Homer Bates, in his book “Lincoln in the Telegraph Office,” the President was remarkably approachable during his time at the telegraph office. Bates recounts that Lincoln would engage in conversation with the cipher operators, inquiring about the messages they were decoding or encoding, or those awaiting processing in the cipher desk’s filing drawer. Lincoln’s routine, Bates notes, involved immediately examining the telegrams in this drawer, starting from the top and reading until he reached the point where he had left off on his last visit.

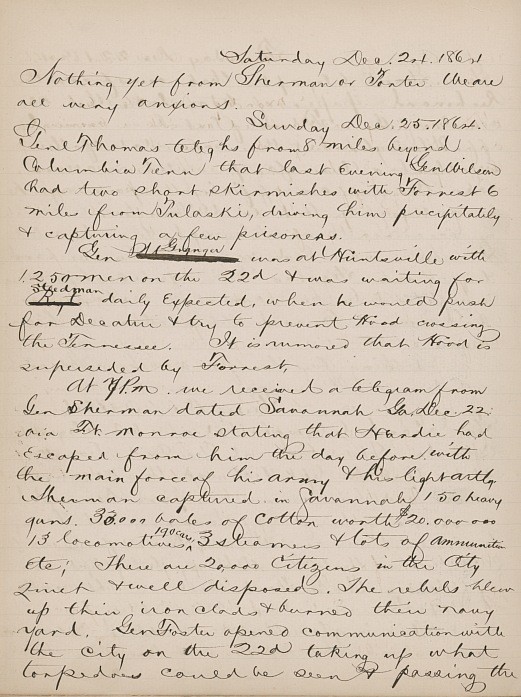

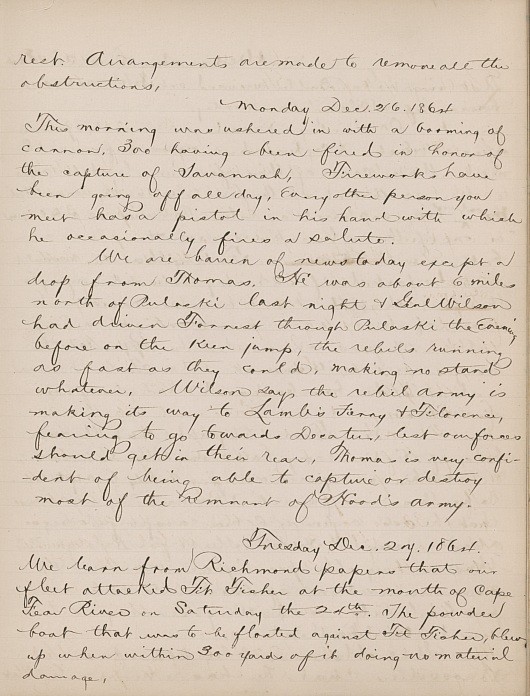

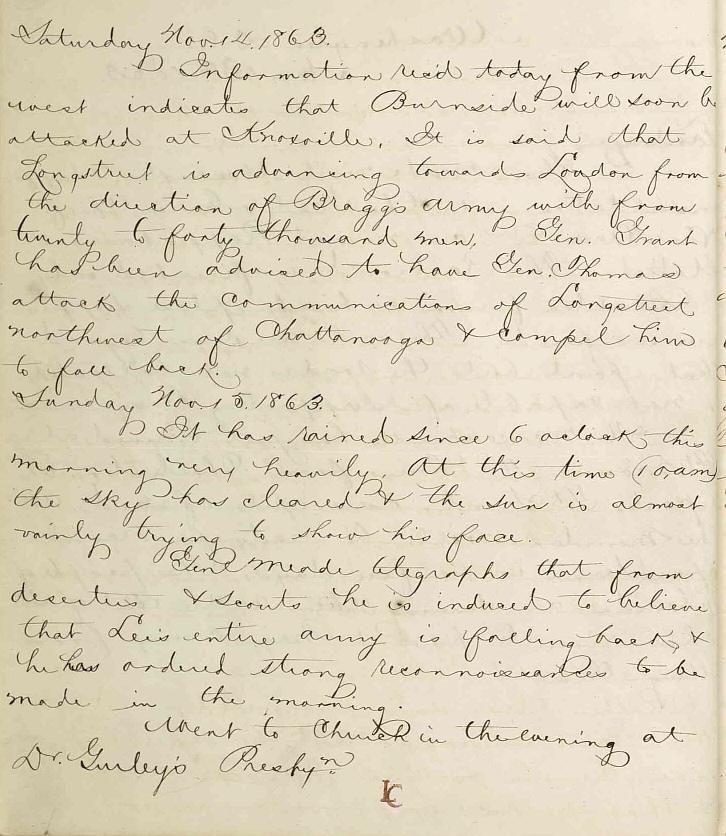

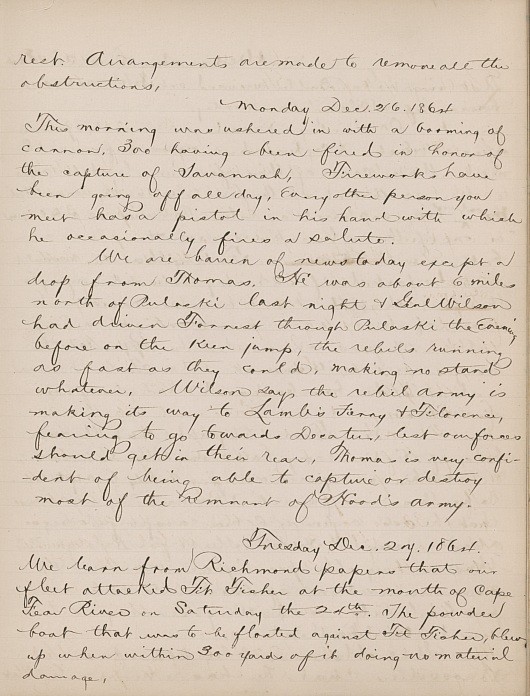

The David Homer Bates Papers (1837-1926) provide valuable primary source material related to this period. This extensive collection spans nearly ninety years, encompassing a wide range of personal documents from Bates’ life. These materials include personal diaries, journals, letters, reproductions of documents, photographs, newspaper clippings, published works, and even drafts and annotated proofs of Bates’ own writings. A particularly relevant section within this collection is the “Civil War File,” containing Bates’ diary and daily journal entries from 1863 to 1865, offering firsthand accounts of the era.

The collection includes a fascinating firsthand account of the Civil War, specifically the period from November 1863 to June 1865, through the diaries and daily journal entries of Davis Homer Bates. Bates’s unique perspective as manager of the War Department telegraph office in Washington, D.C., offers unparalleled insight into the real-time flow of military intelligence during this crucial phase of the conflict. His writings provide a day-to-day narrative of the telegraphic communications that underpinned the Union war effort.

Another significant portion of the archive consists of a compilation of documents spanning the entire Civil War (1861-1865). This section features a diverse range of materials, including personal notes, official correspondence, and endorsements from President Abraham Lincoln himself. The collection also boasts letters from prominent Civil War commanders on both sides of the conflict, adding valuable perspectives to the historical record. Specifically, it includes correspondence exchanged between President Lincoln and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, as well as letters written by several notable Confederate generals, such as Robert E. Lee, Jubal A. Early, and others.

A third segment of the collection focuses on the personal and professional correspondence of Davis Homer Bates, covering a period from 1864 to 1926. This section provides a glimpse into Bates’s life beyond his wartime duties, showcasing his relationships with prominent individuals of the era. The letters reveal his interactions with figures such as Andrew Carnegie, General Thomas T. Eckert (a key figure in military telegraphy), Samuel Morse (the inventor of the telegraph), and Robert Todd Lincoln (the son of the President). The inclusion of retained copies of letters written by Bates himself adds further depth to this personal correspondence.

Finally, the collection includes a section of facsimiles dating from 1862 to 1865. This section offers reproductions of significant documents, including notes and letters from Abraham Lincoln, along with examples of Confederate cipher codes and other miscellaneous materials. A particularly noteworthy item is a handwritten facsimile of Lincoln’s prediction of the 1864 Electoral College vote, created in the War Department Telegraph Office on October 13th, 1864, weeks before the election. This provides a unique and compelling glimpse into Lincoln’s thinking during a critical period in his presidency.

Among the documents seized by General Grant’s forces in Richmond, Virginia, in April 1865, within the State Department archives, was a copy of a Confederate cipher. This cryptographic system facilitated covert communication between Jefferson Davis, the Confederate President; Judah P. Benjamin, the Secretary of State; and J.P. Benjamin, the Secretary of the Treasury, all based in Richmond. Their encrypted messages were exchanged with Confederate operatives in Canada, namely Clement C. Clay and Jacob Thompson, and with other secret agents operating in New York City, including J.H. Cammack.

The collection, spanning from 1837 to 1926, is a diverse assortment of materials. It comprises a wide range of documents, including articles, speeches, published books, biographical information, photographs, and various other items.

This particular collection includes digitized versions of two books authored by David Homer Bates.

One of these books, “Lincoln in the Telegraph Office; Recollections of the United States Military Telegraph Corps during the Civil War” (1907), offers a unique perspective on Abraham Lincoln. Bates’ introduction highlights the lack of attention paid by Lincoln’s biographers to his extensive use of the military telegraph. He emphasizes that Lincoln spent a considerable portion of his waking hours in the War Department telegraph office, more so than in any other location except the White House. This constant presence, argues Bates, provided a more candid insight into Lincoln’s personality than other settings.

The book’s chapters cover a broad spectrum of topics, providing a detailed account of the military telegraph’s role during the Civil War. These topics range from the organizational structure of the Military Telegraph Corps and the inner workings of the War Department Telegraph Office to the use of codes and intercepted Confederate messages. Furthermore, the book delves into significant events and figures of the era, including McClellan’s conflicts with the administration, Lincoln’s involvement in military operations, the drafting of the Emancipation Proclamation, key battles such as Gettysburg and Vicksburg, Lincoln’s interactions with various generals, notable logistical feats, instances of misinformation, and critical moments like Grant’s Wilderness Campaign and the attack on Fort Stevens.

This passage discusses several key events surrounding Abraham Lincoln during the Civil War, drawing heavily from the recollections of David Homer Bates, a telegraph office manager, as detailed in his book, “Lincoln’s Stories Told by Him in the Military Telegraph Office.” The review highlights the book’s authenticity and its value as a primary source.

The excerpt touches upon Lincoln’s anxieties about potential electoral defeat, hinting at the political uncertainties he faced. The mention of conspirators in Canada suggests the existence of plots against the Union, possibly involving external actors. The attempted burning of New York City underscores the scale of sabotage efforts during the war. Grant’s order for the removal of a certain Thomas (the text doesn’t specify who) indicates internal conflicts and the president’s involvement in military command decisions. The failed peace conference at Hampton Roads highlights the difficulties in achieving a negotiated end to the conflict.

The final days of Lincoln’s life are alluded to, leading directly to the assassination itself. Payne, identified as the assassin, is mentioned, suggesting a focus on the perpetrator’s role. Finally, the contrast between Lincoln’s and Stanton’s demeanor suggests a difference in personality and approach to the presidency and the war effort.

The sample diary entries illustrate the immediacy and impact of news during the war. The delay in receiving news of Sherman’s victory in Savannah exemplifies the communication challenges of the era. The thirty-two-day period of suspense highlights Lincoln’s reliance on timely information from the front lines. The diary entry’s description of the jubilant celebrations in Washington upon receiving news of Savannah’s capture emphasizes the significance of the victory for Northern morale. The diary itself serves as a powerful testament to the daily life and experiences of those directly involved in the war effort, offering a firsthand account of the emotional impact of major events.

Timeline of Events from the David Homer Bates Papers

1861

- Early 1861: The United States Military Telegraph Corps is established soon after the start of the Civil War.

- 1861: David Homer Bates, David Strouse, Samuel M. Brown, and Richard O’Brian leave the Pennsylvania Railroad Company to help form the Telegraph Corps.

1862

- February 1862: President Lincoln takes control of the nation’s commercial telegraph lines, making them available for use by Western Union.

- March 1862: Secretary of War Edwin Stanton centralizes all telegraph traffic in the War Department’s old library, next to his office.

1863-1865

- November 1863 – June 1865: David Homer Bates keeps a diary and daily journal detailing his experiences as manager of the War Department telegraph office in Washington. These entries provide valuable insights into military intelligence activities during the Civil War and offer a real-time account of the telegraphic communications throughout the conflict.

- December 22, 1864: General Sherman telegraphs President Lincoln informing him of the fall of Savannah, relieving weeks of anxiety and sparking celebrations in the North.

1864

- October 13, 1864: President Lincoln drafts an estimate of the 1864 Electoral Vote while at the War Department Telegraph Office.

1865

- April 1865: General Grant captures Richmond, leading to the discovery of a Confederate cipher code used by President Davis, Secretary of State Judah P. Benjamin, Secretary of Treasury J.P. Meaminger, and Confederate agents in Canada and New York City.

Post-War

- 1907: David Homer Bates publishes “Lincoln in the Telegraph Office,” based on his experiences and interactions with President Lincoln during the Civil War.

- 1926: Bates publishes “Lincoln Stories Told by Him in the Military Office in the War Department During the Civil War,” a collection of anecdotes and stories shared by Lincoln in the telegraph office.

Cast of Characters:

Abraham Lincoln: President of the United States during the Civil War. He frequented the War Department telegraph office to send and receive messages, finding it a respite from the constant demands of the presidency. Lincoln drafted the Emancipation Proclamation while at the telegraph office and often engaged in conversations with the telegraph operators.

David Homer Bates: Military telegrapher and author who served as manager of the War Department telegraph office from 1863 to 1865. He kept detailed diaries and journals of his experiences, providing a valuable historical record of the period. Bates later published two books based on his wartime experiences, “Lincoln in the Telegraph Office” (1907) and “Lincoln Stories Told by Him in the Military Office in the War Department During the Civil War” (1926).

Edwin M. Stanton: Secretary of War under President Lincoln. He ordered the centralization of all telegraph traffic in the War Department telegraph office, making it a hub of military communication during the war.

Anson Stager: Official of the Western Union Telegraph Company and General Manager of the Military Telegraph Corps.

David Strouse, Samuel M. Brown, Richard O’Brian: Telegraph operators who, along with Bates, left the Pennsylvania Railroad Company to join the Military Telegraph Corps.

Confederate Figures:

- Jefferson Davis: President of the Confederate States of America.

- Judah P. Benjamin: Confederate Secretary of State.

- J.P. Meaminger: Confederate Secretary of the Treasury.

- Robert E. Lee, James Lawson Kemper, Edmund Kirby Smith, Richard Stoddert Ewell: Confederate generals whose letters are included in the David Homer Bates Papers.

- Clement C. Clay and Jacob Thompson: Confederate agents in Canada.

- J. H. Cammack: Confederate agent in New York City.

Other Notable Individuals:

- General William Tecumseh Sherman: Union General who captured Savannah in December 1864.

- Andrew Carnegie, General Thomas T. Eckert, Samuel Morse, Robert Todd Lincoln: Correspondents of David Homer Bates, as evidenced by letters in his collection.

- Charles T. White: Reviewer for the New York Herald-Tribune who lauded Bates’ second book for its authenticity and historical value.

This information extracted from the provided text provides a glimpse into the vital role played by the telegraph during the Civil War and highlights the personal connection President Lincoln had with this technology. The timeline and cast of characters offer a valuable framework for understanding the historical context and significance of the David Homer Bates Papers.