Description

Wounded Knee: A Timeline and Cast of Characters Timeline of Events:

- 1889: Wovoka, a Paiute shaman, has a vision and initiates the Ghost Dance religion, promising a future of peace and plenty for Indians.

- Late 1880s-Early 1890s: Lakota Sioux face hardship due to land loss, treaty violations, dwindling bison populations, and forced farming on infertile land. The Ghost Dance gains popularity among various tribes, including the Lakota, as a means to regain their way of life and hope.

- October 1890: The Ghost Dance movement reaches the Sioux at the Standing Rock Agency, further fueling discontent due to ration cuts and land reductions. The movement’s pacific message becomes intertwined with anti-white sentiment.

- September 1890: White settlers in Nebraska and the Dakotas become alarmed by rumors of Sioux war preparations, leading to requests for military protection and many settlers abandoning their homes and businesses.

- November 1890: President Benjamin Harrison orders the military to take control of Lakota reservations.

- December 15, 1890: James McLaughlin, commissioner of the Standing Rock Agency, sends Indian police to arrest Sitting Bull. Sitting Bull is killed during the confrontation.

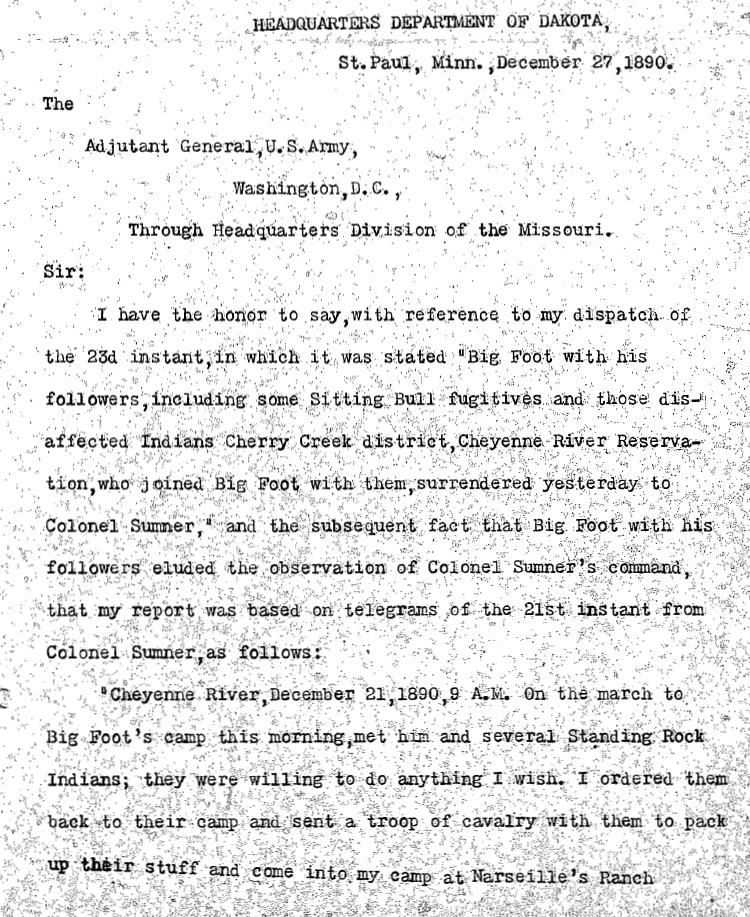

- Late December 1890: Spotted Elk (Big Foot), leader of a band of Minneconjou Lakota, learns of Sitting Bull’s death and decides to move his people from the Standing Rock Agency to the Pine Ridge Agency seeking safety.

- December 28, 1890: Major Samuel Whitside and the 7th Cavalry intercept Big Foot’s band. Big Foot surrenders peacefully. The band is moved to a campsite on Wounded Knee Creek. Colonel James W. Forsyth arrives that night and orders the placement of Hotchkiss cannons around the camp.

- December 29, 1890:Members of the 7th Cavalry, under Col. Forsyth, enter the Lakota camp to disarm them.

- A confrontation arises when a deaf Lakota man named Black Coyote refuses to surrender his weapon, a shot goes off, the reason is unclear.

- Medicine man, Yellow Bird begins proclaiming tenants of the Ghost Dance and incites some Lakota men to attack members of the 7th Cavalry with hidden weapons.

- Soldiers begin firing indiscriminately into the camp, killing Lakota men, women and children. Lakota men fight back with any weapons they could access.

- Lakota survivors attempt to flee the camp and many are hunted down by soldiers.

- Approximately 150 Lakota people, including 60 women and children, are killed (some accounts place the number killed much higher, with one account having 90 warriors and approximately 200 women and children.) 25 soldiers are killed, and 39 are wounded, 6 fatally. It is theorized that some soldiers were killed by friendly fire.

- December 30, 1890: The 7th Cavalry, under Col. Forsyth, fights with Indians near the Drexel Catholic Mission, the day following Wounded Knee.

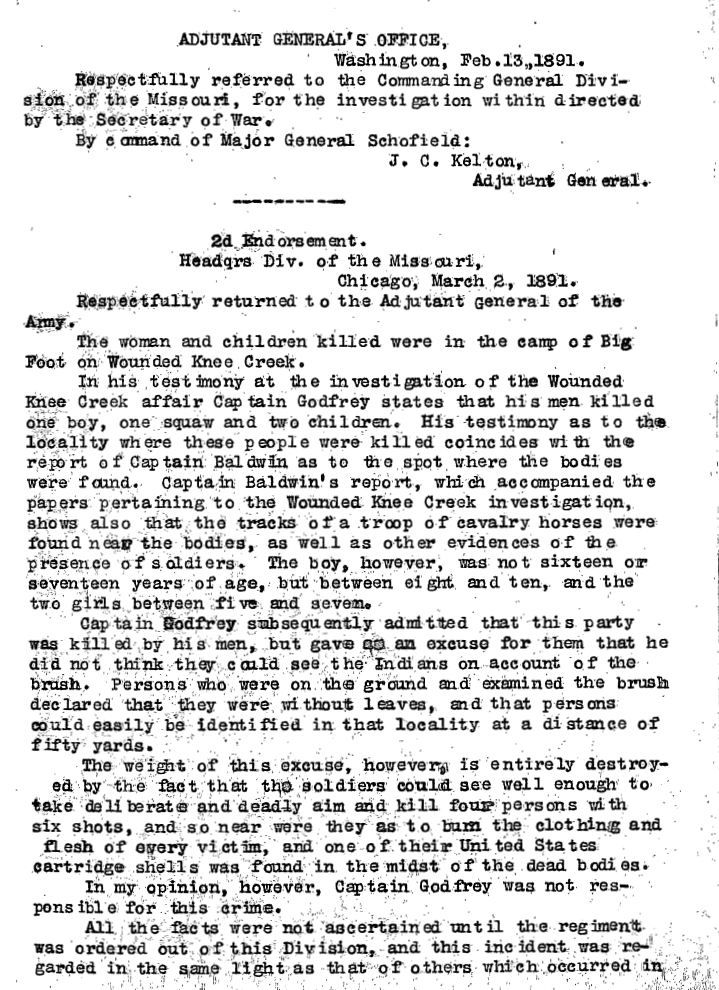

- January 1891:The military launches an investigation into the events at Wounded Knee, led by Major J. Ford Kent and Captain Frank D. Baldwin.

- Major General Nelson Miles is appalled by the event and calls it an “unjustifiable massacre.” He relieves Colonel Forsyth of command.

- The Kent-Baldwin investigation concludes that troops were not properly disposed of and that noncombatants were killed.

- Major General John M. Schofield, Commanding General of the Army, and Secretary of War Redfield Proctor interpret the investigation differently. They believe that the actions of the 7th Calvary were done with “excellent discipline and, in many cases, by great forbearance”. They order Forsyth be reinstated as commander of his regiment.

- 1891: The Annual Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs covers the incident at Wounded Knee, among the coverage of relations between the United States and indigenous peoples in North America.

- 1890-1891 Brig. Gen. Thomas H. Ruger submits a report to the Adjutant General, U.S. Army, on the operations of the Sioux campaign conducted by the Department of Dakota.

- 1895-1896: James Forsyth (by then a brigadier general) submits reports to the Secretary of War, defending his actions at Wounded Knee and Drexel Mission.

- 1906-1919: Eli Seavey Ricker conducts interviews with American Indians, including Joseph Horn Cloud, a survivor of Wounded Knee.

- 1939: Retired Brigadier General E.D. Scott writes an article in The Field Artillery Journal in response to the term “Wounded Knee Massacre”, and refers to official reports to counter the use of that terminology.

- 1952: The National Park Service creates a report on the historical investigation of the Wounded Knee Battlefield site to determine its national significance.

- 1972: The National Park Service issues reports relating to the creation of a Wounded Knee memorial, and the site’s nomination to the National Register of Historic Places.

- 1973: Retired Brigadier General S.L.A. Marshall writes a repudiation of calling the 1890 event a massacre, spurred by the AIM occupation of Wounded Knee.

- 2002: Major Samuel L. Russell publishes a master’s thesis on the cavalry career of Brigadier General Samuel M. Whitside.

- 2011: The National Park Service issues a report on the nomination of Fort McPherson National Cemetery to the National Register of Historic Places.

Cast of Characters:

- Wovoka: A Paiute shaman who initiated the Ghost Dance religion in 1889, promoting a vision of a peaceful and prosperous future for Indians. His teachings spread widely among tribes facing hardship.

- Spotted Elk (Big Foot): Chief of the Minneconjou Lakota. He led his band away from the Standing Rock Agency after the death of Sitting Bull, seeking refuge at the Pine Ridge Agency. He and many of his people were killed at Wounded Knee.

- Sitting Bull: A prominent Lakota leader who was killed during an attempt to arrest him at the Standing Rock Agency for his association with the Ghost Dance. His death further heightened tensions.

- Hump: A discontented Sioux leader whose influence grew due to the Ghost Dance movement.

- James McLaughlin: Commissioner of the Standing Rock Agency who ordered the arrest of Sitting Bull.

- Major Samuel Whitside: Led the 7th Cavalry troop that intercepted Big Foot’s band and brought them to Wounded Knee Creek.

- Colonel James W. Forsyth: Commander of the 7th Cavalry at Wounded Knee. He was relieved of command by General Miles, but later reinstated by the Secretary of War.

- Black Coyote: A deaf Lakota tribesman whose refusal to surrender his weapon is often cited as the catalyst for the violence at Wounded Knee.

- Yellow Bird: A Lakota medicine man who began proclaiming Ghost Dance tenants and inciting attacks at Wounded Knee

- Major General Nelson Miles: Commander of field operations at the time of Wounded Knee. He viewed it as a massacre and relieved Forsyth of his command.

- Major J. Ford Kent: Division Inspector General, and one of the leaders of the court of inquiry into the Wounded Knee incident.

- Captain Frank D. Baldwin: Assistant Inspector General, and one of the leaders of the court of inquiry into the Wounded Knee incident.

- Major General John M. Schofield: Commanding General of the Army. He did not believe the Wounded Knee incident was a massacre, and supported the actions of the 7th Calvary.

- Redfield Proctor: Secretary of War, he agreed with Schofield that no further proceedings in the case were necessary and ordered that Forsyth be returned to his command.

- Daniel S. Lamont: Secretary of War during the time when Forsyth wrote his reports defending his actions at Wounded Knee and Drexel Mission.

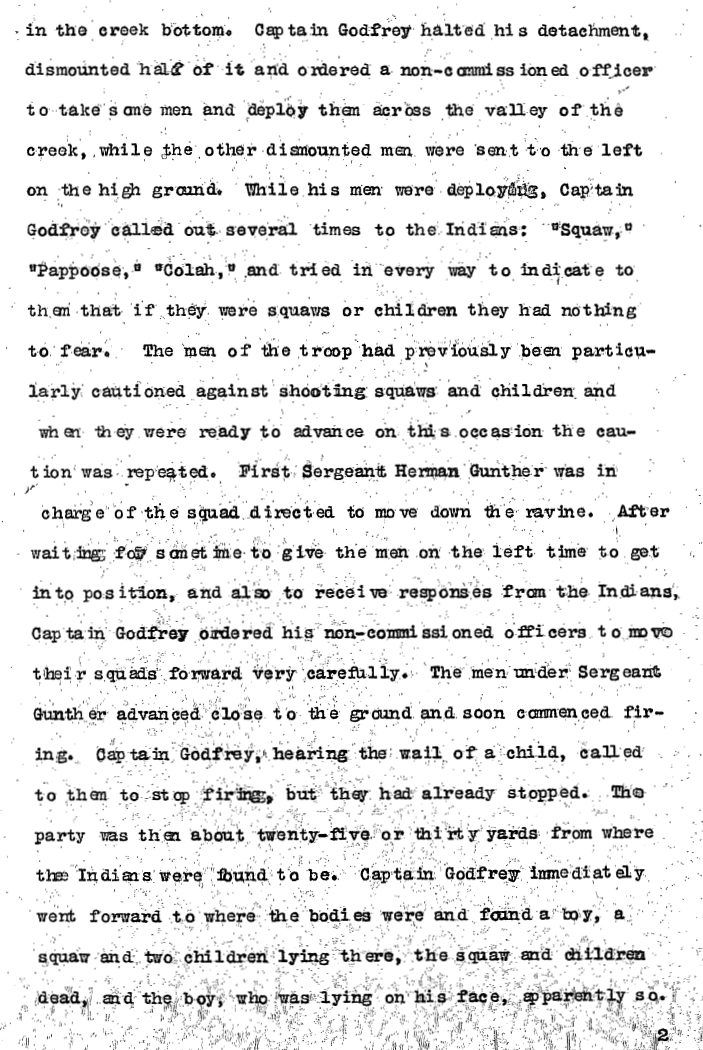

- Major Peter D. Vroom: Inspector General, Department of the Missouri, who led an investigation into the deaths of four Indians found near the Wounded Knee battlefield.

- Col. Edward M. Heyl: Inspector General, Division of the Missouri, who prepared a report on the fight near the Drexel Catholic Mission the day after Wounded Knee.

- Brig. Gen. Thomas H. Ruger: Submitted a report to the Adjutant General, U.S. Army, on the operations of the Sioux campaign conducted by the Department of Dakota.

- Eli Seavey Ricker: Civil War veteran, historian, lawyer, judge and journalist. He interviewed Joseph Horn Cloud, a survivor of Wounded Knee.

- Joseph Horn Cloud: A survivor of the Wounded Knee Massacre, he was a young man when it occurred, and his family was killed in the fighting. He was interviewed by Eli Seavey Ricker.

- E. D. Scott: Retired Brigadier General who wrote a 1939 article defending the actions of the Army at Wounded Knee, referring to official documents to defend his assertions.

- S.L.A. Marshall: Retired Brigadier General who wrote a 1973 article repudiating the term “Wounded Knee Massacre”, referencing the AIM occupation of Wounded Knee and arguing in support of the Army’s actions.

- Major Samuel L. Russell: Author of a 2002 master’s thesis on the career of Brigadier General Samuel M. Whitside.

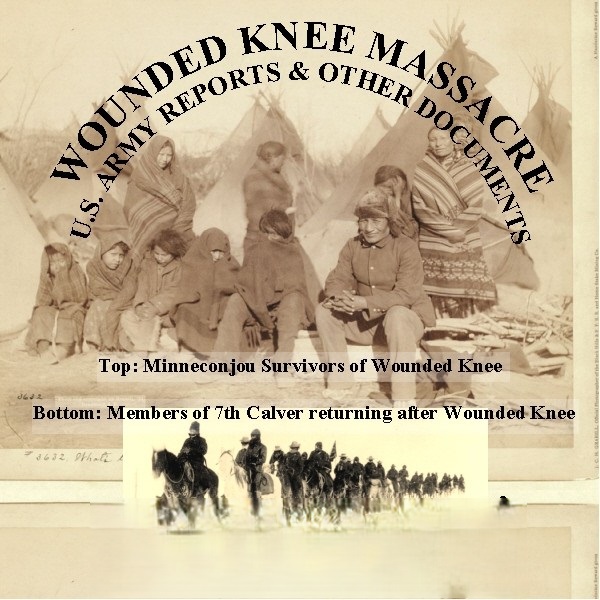

This collection comprises 2,150 pages of documents from the National Archives, detailing the U.S. Army’s investigation into the Wounded Knee Massacre and the broader Sioux Campaign of 1890-1891. The collection also features photographs, official reports from the Indian Affairs Commissioner and the National Park Service, and relevant military publications. A clash between the 7th Cavalry and a group of Sioux, resulting in a high number of Native American deaths—many women and children—remains a subject of ongoing historical debate.

These documents offer primary source material from the Army’s initial investigations, revealing their attempts to reconstruct the events and assess potential misconduct. The materials encompass a range of documents, including letters, telegrams, maps, and reports, covering both the immediate aftermath of the Wounded Knee incident (which the Army termed a battle) and the preceding period of Sioux unrest. Furthermore, the collection includes reports from Colonel Forsyth defending his actions at Wounded Knee and Drexel Mission, alongside other correspondence related to the Sioux uprisings and the Army’s response during the Ghost Dance movement. The massacre occurred on December 29, 1890. Wounded Knee is uniquely linked to the perceived closure of the American frontier. Centuries of conflict between cultures in North America led to the complete loss of Native American sovereignty.

The Wounded Knee National Park Service guide describes the event of December 29, 1890, as the final major conflict between Native Americans and the U.S. military, concluding nearly four hundred years of fighting. While unintentional on both sides, stemming from a tense misunderstanding rather than planned aggression, the event more closely resembles a massacre than a battle. For Americans in the 20th century, it represents a national shame regarding the treatment of Native Americans.

The last significant violent encounter between Native Americans and the U.S. Army happened at Wounded Knee, South Dakota, on December 29, 1890. It’s known as both a massacre and a battle, with the terminology reflecting differing viewpoints. There are two contrasting interpretations of this engagement between the U.S. Seventh Cavalry and Chief Spotted Elk’s followers, marking the end of the 1890-91 Sioux Campaign. The late 19th century was a period of hardship and resistance for many Native American tribes, particularly the Lakota. New laws dispossessed the Lakota of vast territories, violating treaty agreements that promised food, shelter, and protection of their lands. The near-extermination of bison, a crucial food source, further exacerbated their plight, forcing them to farm unproductive land during a drought. Facing these hardships, many tribes, including the Lakota, adopted the Ghost Dance religion as a means of cultural preservation and self-determination. The culmination of this oppression and hostility resulted in the Wounded Knee massacre.

The U.S. military viewed Wounded Knee as the end of Native American resistance in the Plains, concluding what they considered the final Indian War. They characterize the event as a battle, not a deliberate killing of unarmed people. The Ghost Dance, originating in 1889 with a Paiute shaman’s vision of a peaceful future, reached the Standing Rock Sioux in October 1890. This religion, as detailed by James Mooney, promised a utopian era of unity for all Native Americans, living and dead, free from suffering. This new world, Wovoka taught, would be achieved through virtuous living and the Ghost Dance itself.

However, among the Sioux, the Ghost Dance took on a different character. Their resentment towards the injustices inflicted by white settlers—ration cuts, land seizures, and other grievances—transformed the movement’s peaceful message. The Sioux interpreted the prophecy to mean the destruction of white people in 1891. This fueled defiance against government officials and empowered influential leaders like Sitting Bull, Big Foot, and Hump. By September 1890, widespread fear gripped white communities in the Dakotas and Nebraska, leading to panic, exodus from rural areas, and urgent pleas for military intervention. The U.S. Army took over Lakota reservations in November 1890, under President Harrison’s orders. Following this, Sitting Bull was arrested and killed on December 15th, 1890, by Indian police acting on the orders of James McLaughlin. Upon hearing of Sitting Bull’s death, Big Foot, a Lakota leader, decided to move his people to a different reservation for safety.

Big Foot’s group, comprising around 350 people, left Standing Rock on December 28th, 1890, intending to reach Pine Ridge. They were stopped by the 7th Cavalry, under Major Whitside, and surrendered without resistance. The army relocated them to Wounded Knee Creek, where additional troops and artillery were deployed.

The next morning, December 29th, soldiers attempted to disarm the Lakota. A dispute arose when a deaf man, Black Coyote, resisted surrendering his rifle, possibly due to misunderstanding or reluctance to part with a valuable possession. A shot was fired, initiating a violent conflict.

Another version of events claims that a medicine man, Yellow Bird, fueled by Ghost Dance beliefs, incited a Lakota attack on soldiers. The soldiers opened fire, and the Lakota responded with whatever arms they possessed. Many Lakota escaped the camp, but some were pursued and murdered by the cavalry. Official records indicate approximately 150 Lakota perished, including 60 women and children. Cavalry casualties numbered 25 dead and 39 wounded, six of whom died from their injuries; some believe many soldiers were killed by their own side.

Alternative accounts suggest a far greater Lakota death toll. These claims cite a 1917 letter from Major General Nelson Miles to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, reporting 90 male and approximately 200 female and child casualties.

Horrified by the event, General Miles called it an unjustified massacre, launched an investigation, and removed Colonel Forsyth from his post. However, the Secretary of War overruled this decision, clearing Forsyth and reinstating him.

The 7th Cavalry’s actions at Wounded Knee sparked immediate controversy. President Harrison ordered an investigation into the killing of women and children. General Miles initiated a formal inquiry into the deployment of troops and the indiscriminate killing of civilians, appointing Major Kent and Captain Baldwin to lead the investigation, which commenced on January 7th. The court issued its final ruling on January 18th. The investigation’s findings, including witness statements, were sent to Washington, accompanied by General Miles’ strong condemnation of Colonel Forsyth’s actions. While Miles’ assessment of inadequate troop deployment was backed by Kent and Baldwin, it contradicted the 7th Cavalry officers’ testimony, who largely defended their commander regarding troop placement and accusations of excessive force.

The Army’s Commanding General, Major General Schofield, and Secretary of War Proctor disagreed with Miles and Kent-Baldwin’s interpretation. Schofield felt the investigation demonstrated the 7th Cavalry’s exemplary discipline and restraint under pressure. Proctor agreed, deeming further action unnecessary and reinstating Colonel Forsyth to his command per the President’s order.

The documents are organized into four volumes, plus Forsyth’s own reports. Each volume contains a detailed index of names and subjects. This index acts as a complete guide to the four volumes’ contents, covering topics like “Indians,” “Interior Department,” and “Troops,” with relevant subcategories. Each entry lists related documents and summarizes their content. This collection is primarily organized chronologically, however, some enclosed documents and supporting materials predate their accompanying letters, thus falling outside the volume’s listed date range. The first two volumes are paginated consecutively from page 1 to 1793. These volumes, titled “Sioux Campaign, 1890-91,” are manuscript copies seemingly compiled by the Army, as are the third (pages 1794-2006) and fourth (pages 2007-2057) volumes.

The first volume (pages 1-650) covers October to December 1890 and contains War Department and Bureau of Indian Affairs communications about the growing “Messiah Craze” and its impact on various Indian agencies. It also includes reports on rising Sioux unrest and military and civilian concerns about the need for potential force; Army records of troop movements and ammunition deliveries; Cheyenne council proceedings explaining Ghost Dance beliefs (pages 110-121); General Miles’ assessment of the military balance between white and Indian forces (pages 279-285); discussions of Indian food supply issues; and early accounts of Sitting Bull’s death, the pursuit of Big Foot’s group, and the Wounded Knee massacre. The second volume, pages 651 to 1793, starts with the findings of the Kent-Baldwin investigation. This includes supporting documents such as orders authorizing the inquiry, a full record of the testimony, relevant letters, the investigators’ conclusions, endorsements from senior officers, and a map of Wounded Knee.

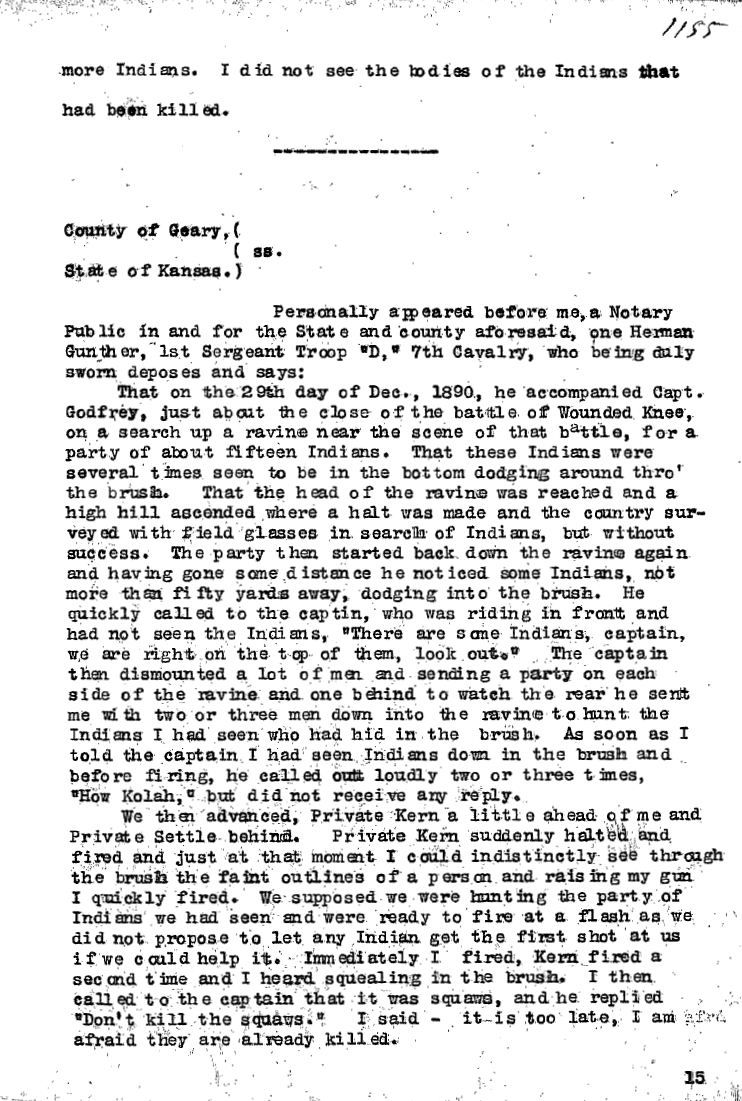

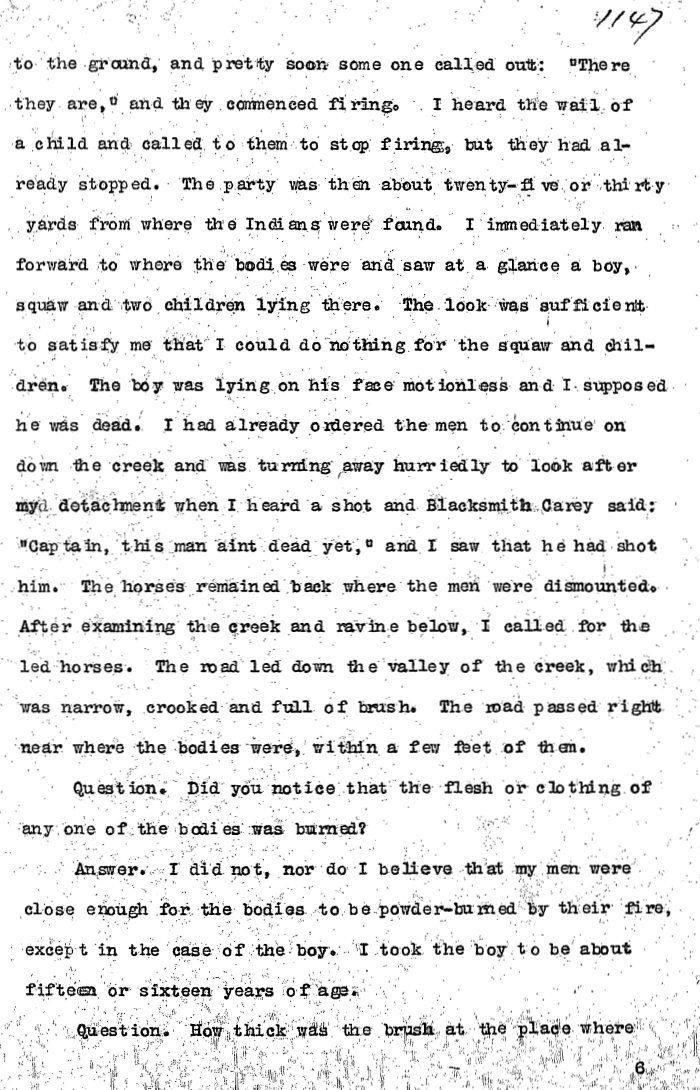

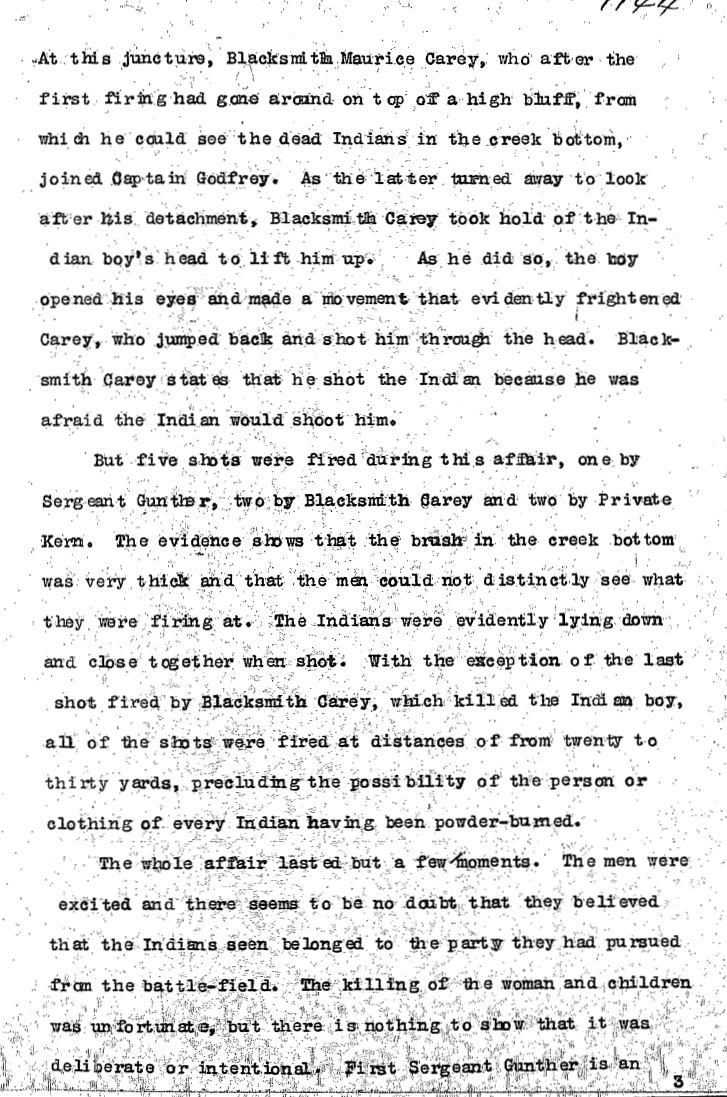

This volume also contains two additional related investigations. Major Vroom’s report (pages 1135-1158) details the killing of four Native Americans near Wounded Knee, and includes supporting evidence such as a letter from the War Secretary, endorsements, and witness statements. Colonel Heyl’s report (pages 1077-1098) examines a subsequent engagement near Drexel Mission, providing witness accounts, correspondence, Heyl’s conclusions, and a battle map. General Miles felt this report supported his assessment of Colonel Forsyth’s incompetence, as indicated in his accompanying letter. Beyond the three initial reports, the second volume includes extensive letters about the final stages of the Sioux conflict and the Native Americans’ situation in early 1891, covering military actions, troop movements, Indian food supply issues, and agency conditions. Details surrounding Sitting Bull’s death are also further elaborated.

The third volume, titled “Headquarters Department of California, Report on Operations Relative to the Sioux Indians in 1890 and 1891 in the Department of Dakota,” (pages 1794-2006) is Brigadier General Ruger’s report to the U.S. Army Adjutant General on the Dakota Department’s Sioux campaign. It details Sioux conditions in 1890, the Ghost Dance movement, and his troops’ actions from November 1890 to January 1891, along with reports from other participating officers.

The fourth volume (pages 2007-2057) contains the Secretary of the Interior’s response to a December 2, 1890 Senate inquiry about Native American weaponry on Nebraska and Dakota reservations. It primarily comprises Indian Affairs Department correspondence from May to December 1890, focusing on the Ghost Dance-related weapon concerns. After the fourth volume, there are two long, unattached reports from Brigadier General James Forsyth to Secretary of War Daniel S. Lamont, dated September 1, 1895, and December 21, 1896. These reports defend Forsyth and his regiment’s actions at Wounded Knee and Drexel Mission. Forsyth challenged the findings of the Kent-Baldwin and Heyl investigations, questioning the legality of the Kent-Baldwin inquiry and accusing General Miles of trying to ruin his reputation. The reports, along with supporting documents and letters, are organized by date.

The collection also contains the 1891 Annual Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, a two-volume, 1,124-page document detailing U.S.-Native American relations, including the Wounded Knee massacre of December 1890.

Furthermore, the collection includes a three-page transcript of an interview conducted in 1906 by Eli Seavey Ricker with Joseph Horn Cloud, a Wounded Knee survivor. Ricker, a multi-talented individual with a diverse career, was working on a book about the conflicts between Native Americans and white settlers when he interviewed Cloud, who had lost family members at Wounded Knee.

Finally, the collection includes a 1939 publication titled “Wounded Knee: A Look at the Record”. A 1939 article in The Field Artillery Journal by Brigadier General E. D. Scott challenged the term “Wounded Knee Massacre,” using archival documents from the 1890-1891 Sioux Campaign to support his argument. A 1973 article in Parameters, by Brigadier General S. L. A. Marshall, similarly rejected the “massacre” label, prompted by the 1973 Wounded Knee occupation. Major Samuel L. Russell’s 2002 master’s thesis, a biography of Brigadier General Samuel M. Whitside, offers a 171-page account of his cavalry career. Forty-five photographs depict Wounded Knee, both before and after the event. Finally, 281 pages of National Park Service documents include a 1952 report assessing the site’s eligibility for national recognition.

A 1972 National Park Service document details the development of a Wounded Knee memorial. A 1972 report, spanning 160 pages, proposed designating Wounded Knee a National Historic Landmark. A concise, two-page National Park Service overview summarizes the Wounded Knee massacre of December 1890. A 2011 report recommended adding Fort McPherson National Cemetery to the National Register of Historic Places. An official map of Badlands National Park is available.

Related products

-

World War II: Australian Military Weekly Intelligence Reports 1943-44

$3.94 Add to Cart -

Vietnam War: CIA Chronology of the Conflict, 1940-1973 (1974)

$1.99 Add to Cart -

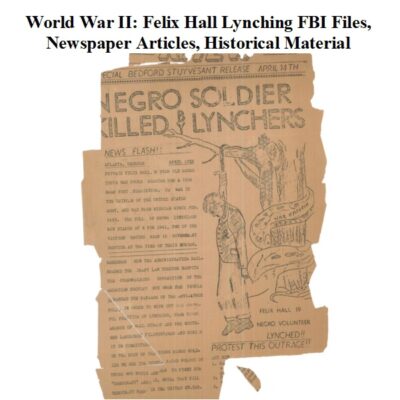

World War II: Felix Hall Lynching – FBI Files, Articles, Historical Records

$9.99 Add to Cart -

Vietnam War: Cryptology in North Vietnam – NSA Official History

$4.90 Add to Cart