Description

WWII Airmen: Evasion and Escape in Enemy Territory

Timeline of Main Events

March 5, 1944:

- Flight Officer Chuck Yeager’s P-51 Mustang is shot down over France. He is wounded and aided by French civilians who hide him. He is then placed into a French escape network.

Approximately March 1944 (following Yeager’s downing):

- Chuck Yeager begins his 23-day, 100-mile journey through the French escape network.

Late March 1944:

- Dr. Albert-Marie Edmond Guérisse (“Pat O’Leary”), who runs the Pat Line escape network in Marseilles, France, is betrayed by an informant to the Gestapo. He is tortured but reveals no information.

April 1944:

- Chuck Yeager crosses the Spanish border after 23 days of evasion.

June 6, 1944 (D-Day):

- The Allied invasion of Normandy, France, takes place.

June 12, 1944:

- Captain Jack Ilfrey is shot down by anti-aircraft fire over Angers, France, six days after the Normandy invasion.

- Chuck Yeager speaks with Allied Supreme Commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower, arguing to be allowed to return to combat.

Mid-June 1944 (following Ilfrey’s downing):

- A French family hides Captain Jack Ilfrey in their home for two weeks. He is given fake identification as a deaf and mute farmer named “Jacques Robert” and a bicycle.

- Captain Jack Ilfrey begins his 150-mile journey on bicycle towards the Allied lines in Normandy, encountering German soldiers.

October 25, 1944:

- Sergeant William Davidson becomes lost in the woods near St. Die, Germany, and is captured by a German patrol.

- Sergeant William Davidson escapes during an interrogation due to a nearby artillery round.

Approximately late October/early November 1944:

- Sergeant William Davidson arrives at the Swiss border, three weeks after his escape.

Undated (likely 1944):

- Major Donald Willis’ plane is struck by anti-aircraft fire over German-occupied Holland and crash-lands during a soccer game. He evades capture by blending in and utilizing civilian assistance.

- Major Donald Willis observes a B-17 catch fire over a Belgian city, sees a parachutist land, and witnesses the airman escape on a German motorcycle.

- Second Lieutenant Robert Laux parachutes over Amiens, France, after his plane is hit. He is aided by a French woodcutter and later encounters German soldiers, using the Hitler salute to his advantage. He is eventually aided by the French Resistance.

- Staff Sergeant William Howell is wounded and bails out over German-occupied territory. He is aided by a French family who remove shrapnel from his wounds. He eventually travels towards Spain with the help of the French Resistance.

- Second Lieutenant Eugene Squier parachutes after his plane is hit near Nantes, France. He is aided by civilians and an elderly couple who fear collaborators. Unable to arrange a return, he later encounters a group of German soldiers attempting to surrender.

Throughout the War (mentioned generally):

- American aircrewmen are shot down over German-controlled territory, primarily in France, Belgium, Holland, Norway, Denmark, and Hungary.

- Thousands of aircrewmen evade capture or escape from German prisons.

- Servicemen utilize evasion and escape training and escape kits.

- Local civilians and national partisan resistance organizations (French, Belgian, Dutch, Czech, etc.) aid escaping servicemen at great risk.

- The Gestapo actively searches for those assisting Allied personnel, with many “helpers” being sent to concentration camps or executed.

- Escaping servicemen risk execution as spies if captured out of uniform.

- Three major organized evasion lines operate in Western Europe: the Pat Line, the Comet Line, and the Shelburne Line.

- Allied intelligence establishes a system to debrief returned evaders and escapees, who are sworn to secrecy.

- Escape and Evasion reports are created by the U.S. War Department to document these experiences, containing questionnaires, interrogation forms, and narratives.

- Evaders and escapees gather valuable intelligence on enemy fortifications, bombing results, military production, infrastructure, troop deployments, and morale.

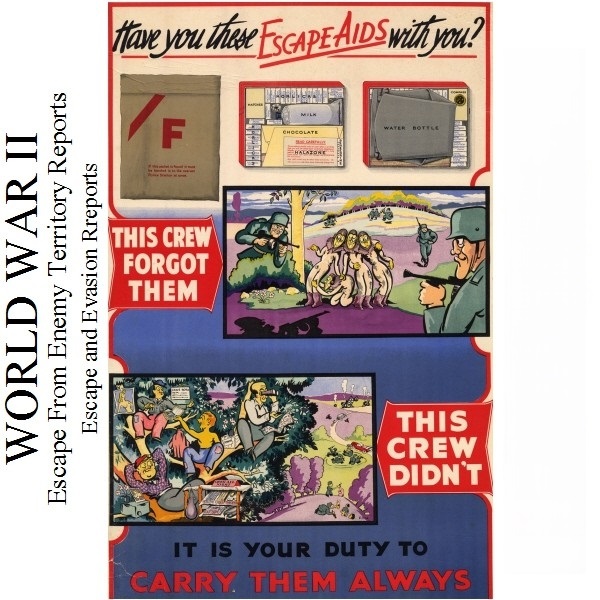

- Escape kits contain maps, compasses, currency, saws, photos, “Pointie Talkies,” phrase cards, and blood chits.

- Benzedrine tablets are provided for energy during escapes.

- Returned evaders and escapees are initially restricted from flying over enemy territory again.

- Some, like Chuck Yeager, successfully petition to return to combat.

- Many evaders and escapees secretly wear “Winged Boot” patches after their return.

By October 1942:

- Allied intelligence establishes a system to debrief returned servicemen in England, who are sworn to secrecy.

Cast of Characters

- Chuck Yeager (Flight Officer): An American P-51 Mustang pilot shot down over France on March 5, 1944. He was wounded but successfully evaded capture with the help of French civilians and an escape network, reaching Spain after 23 days. He later argued to General Eisenhower and was permitted to return to combat, becoming a flying ace. After the war, he became famous for breaking the sound barrier.

- Jack Ilfrey (Captain): An American pilot from Houston, Texas. He had a prior incident in November 1942 where he was interned in neutral Portugal but managed to steal his plane back and fly to Gibraltar. On June 12, 1944, he was shot down over Angers, France. He was hidden by a French family, given false identity papers, and attempted to reach Allied lines disguised as a deaf and mute farmer, encountering various challenges. He eventually reached British forces.

- William Davidson (Sergeant): An American sergeant who became lost near St. Die, Germany, on October 25, 1944, and was captured. He escaped during an interrogation and reached the Swiss border three weeks later. He was briefly held with German officers in Switzerland before being returned to Allied control.

- Donald Willis (Major): An American major whose plane was shot down over German-occupied Holland and crash-landed during a soccer game. He successfully evaded capture with the help of Dutch and Belgian civilians and the Belgian underground. He also recounted witnessing another downed American airman escape on a German motorcycle.

- Robert Laux (Second Lieutenant): An American pilot and mail clerk from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, whose plane was hit over Amiens, France. He parachuted and was aided by a French woodcutter who gave him civilian clothes. He used unexpected tactics, like returning Hitler salutes, during encounters with German soldiers. He was eventually assisted by the French Resistance on an escape route.

- William Howell (Staff Sergeant): An American tail gunner from North Carolina. He was wounded and bailed out over German territory. He evaded Germans in the woods and was later taken in by a French family who treated his wounds. He was disguised as a boy scout and eventually assisted by the French Resistance in traveling towards Spain.

- Eugene Squier (Second Lieutenant): An American co-pilot and dental technician from San Francisco, California. His plane was hit near Nantes, France, forcing him to parachute. He was aided by several civilians and an elderly couple who hid him. When Allied forces advanced, he encountered a group of German soldiers attempting to surrender, whom he eventually convinced of his identity.

- Albert-Marie Edmond Guérisse (Dr.) / “Pat O’Leary”: A key figure in the French Resistance who ran the Pat Line (also known as the O’Leary or P.A.O. Line), a major Allied escape network based in Marseilles. He was betrayed to the Gestapo in March 1943, endured torture, and was sent to a concentration camp but survived the war.

- Dwight D. Eisenhower (General): The Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force. Chuck Yeager directly appealed to him to be allowed to return to combat after his evasion, and Eisenhower granted permission after consulting with the War Department.

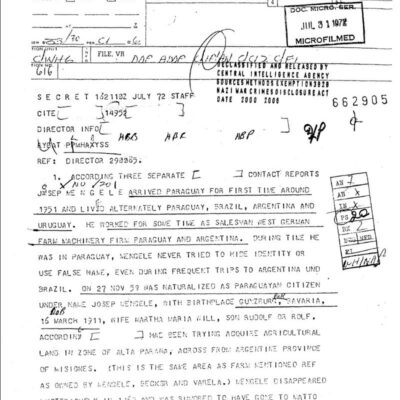

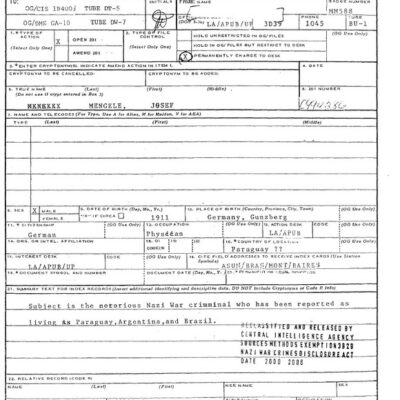

World War II Escape From Enemy Territory Reports

44,105 pages composed of 2,950 Escape and Evasion reports.

These reports were created by the United States War Department, U.S. Forces, European Theater, Military Intelligence Service (MIS) Escape and Evasion Section (MIS-X) and Interview Section, Collection and Administration Branch. The source of the information contained in these Escape and Evasion reports are chiefly from American aircrewmen who escaped from behind enemy lines.

Over the course of World War II thousands of American Aircrewmen survived the crash of their aircraft into German controlled territory. Mostly in France, Belgium, Holland, Norway, Denmark, and Hungary. Many successfully evaded capture by German troops or later escaped from German prisons. The servicemen used their evasion and escape training and their escape kits to aid their self-extraction from enemy territory. Many times they were aided, at great risk, by local civilians, and the French, Belgium, Dutch, Czech or other national partisan resistance organizations.

The Gestapo searched for those aiding the escape of allied personnel. Hundreds of the “helpers” who got American servicemen back to allied territory were sent to concentration camps or were executed. The servicemen also put themselves at risk. Their attempt to return, instead of waiting out the war in a POW camp, often involved ditching their uniforms and wearing civilian clothing. This meant that they lost protections under the Geneva Convention, and if captured could have been executed as spies. Those who managed to walk out of German occupied Europe were referred to as belonging to the “blister club.”

There were three major organized evasion lines in Western Europe the Pat Line, the Comet Line and the Shelburne Line. These were established by allied intelligence and local resistance fighters. The Pat Line, also known as the O’Leary or P.A.O. Line, was run by Dr. Albert-Marie Edmond Guérisse, operating under the alias Pat O’Leary. The Pat Line was based in Marseilles, France. In March of 1943, an informant told the Gestapo of Guérisse’s activity. He endured torture without revealing any information. He was sentenced to death and sent to a concentration camp, but managed to survive the war.

By October 1942, allied intelligence had set up a system to gain intelligence from the returned. They were usually sent to England to be debriefed by intelligence officers. They were immediately sworn to secrecy about their experiences. They signed a document that included the statement, “Information about your escape or your evasion from capture would be useful to the enemy and a danger to your friends. It is therefore SECRET.”

These reports are firsthand accounts of the experiences of many of those who made it back to allied controlled territory. They usually contain answers given to a brief questionnaire concerning the use of escape and evasion training and equipment; an interrogation form with unit designation, target information, number of missions flown, date considered missing in action, date returned to U.S. or allied control, country of escape or evasion, and a listing of crew members or other service personnel with official disposition; a verification of the identity and trustworthiness of escapee or evader; a certificate safeguarding prisoner of war and/or escape and evasion information; an outline of topics to be covered in the narrative; and a typed or handwritten narrative that documented the escape and evasion experience of the escapee or evader.

Many of the evaders and escapees had spent weeks behind enemy lines. They had information about fortifications, results of allied bombing, its accuracy and the extent of bomb damage, military production, the condition of railroad lines, airfields, troop encampments, coastal and interior defenses, anti-aircraft batteries, radar installations, location of enemy factories and ammunition dumps, and enemy and civilian morale that could only be had by someone who had spent time on the ground.

The reports contain information about the use and effectiveness of escape tools provided to the aircrew. Survival kits were packed into small satchels often referred to as their “purse.” Evasion purses were custom-made for specific areas, they contained escape maps, compasses, local currency and escape saws. They contained passport type photos of the airmen in civilian clothing to be used to create fake identification if the crewman were to enter one of the escape lines.

The kits contained “Pointie Talkies” and phrase cards to aid in communication with local civilians. An Airman would point to the words and phrases and followed instructions on pronunciation contained in a “pointie talkie” or on a phrase card. Blood chits inside the kits read, “I am an American, misfortune forces me to seek your assistance…” Blood chits offered a reward to those who provided assistance. They also identified a flier’s nationality and carried messages in several languages that requested aid. Each blood chit was individually numbered to identify specific aircrew.

The kits also contained Benzedrine tablets to give “energy” to the airmen so they could pursue their escape.

After returning to duty many evaders or escapees had terrific stories that they were forbidden to tell. They often bought a custom-made “Winged Boot” patch at Hobson and Sons in London. This was an unauthorized uniform item, so it was worn under the left-hand coat lapel.

CHUCK YEAGER

The subject of one Escape and Evasion report is Flight Officer Charles Yeager, better known as Chuck. Chuck Yeager after the end of World War II piloted the first aircraft to break the sound barrier. Later he became the first to fly mach 2. On March 5, 1944, Flight Officer Yeager’s P-51 Mustang was shot down over France. French civilians took the wounded pilot, changed him into civilian clothing and hid him in a barn. He was then placed into a French escape network. Twenty-three days and 100 miles later Yeager crossed the Spanish border.

It was regulation that evaders and escapees would not be allowed to fly over enemy territory again. Many of the returned had knowledge about Resistance allies. The military did not want to risk that this information could be extracted by the Germans.

Yeager was able to speak face to face with Allied Supreme Commander, General Dwight D. Eisenhower on June 12, 1944. He argued that he should be allowed to return to combat because with the Allies’ invasion of France, French Resistance members were openly fighting alongside Allied troops, so there was little or nothing he could reveal if shot down again that would endanger those who had helped him flee. Eisenhower got permission from the War Department to allow Yeager to return to combat. After he returned to his unit he was credited with shooting down 10 1/2 more German aircraft.

Other Reports include:

Escape and Evasion Report Number 759 – Captain Jack Ilfrey

Captain Jack Ilfrey, from Houston, Texas, first escape is not captured by an E&E report. In November 1942, on a ferry flight from England to North Africa, Ilfrey’s plane had a fuel malfunction and he was forced to land in Portugal. Portugal was neutral during World War II. Portuguese officials seized his P-38 and interned Ilfrey. Later he was taken to his plane to instruct the Portuguese how to fly the now refueled aircraft. While sitting in the cockpit Ilfrey quickly started it up, took off and flew it to Gibraltar.

On June 12, 1944, six days after the Normandy invasion, Ilfrey was shot down by anti-aircraft fire over Angers, France. A French family hid him in their home for two weeks. He was given fake identification papers and a bicycle. Ilfrey’s new identity was that of a deaf and mute French farmer named “Jacques Robert.” He then set off on the bicycle to begin his attempt to make a 150 mile trek to the lines in Normandy wearing a beret, old French slippers, Dutch trousers that buttoned up the side, a green shirt, and a blue jacket.

The road he took was well traveled by German soldiers. During his journey a German soldier on foot ordered him to stop and tried to take his bicycle. He held on to the bike as the soldier tried to take it away, saying in French “mama and papa”. The soldier gave up as a truck load of German soldiers passed by and the soldier hitched a ride. Further down the road he stopped at a farmhouse and asked a Frenchman for water. After the Frenchman gave him the water, he began asking Ilfrey questions. Ilfrey pointed to his ears and said, “sourd,” the French word for deaf. Further down the road he came across two German soldiers carrying a third soldier, whose leg had been shot off. When they attempted to take his bike, he again said in French “mama and papa,” but this time it had no effect and they commandeered the bike.

Further north down the road, now traveling by foot, a group of German soldiers emerged from a wooded area and dragged him off the road and forced him into their trench. Ilfrey assumed that they thought he was a Frenchman, with Allied patrols near, they thought he might give away their position. When he tried to leave the Germans prevented it. He remained in the trench with the German soldiers for two hours as British shells landed nearby. One of the German soldiers in the trench was hit in the stomach by a shell fragment. The Germans put him in a wheel barrel and ordered Ilfrey to take him south down the road to a German field hospital. When he arrived with the soldier at the medical station the attendants gave Ilfrey chocolate and cigarettes and told him that he should continue heading south to Fontenay. From there he went west to Tilly. A French farmer told him that there were allied troops outside of St. Pierre. While walking on a dirt road he could see British helmets over the top of hedges. He heard someone yell in English to get that Frenchman out of the way. A British sergeant grabbed him from behind a hedge. After indentifying himself as an American flyer, he was sent to a forward headquarters.

Escape and Evasion Report Number 2756 – Sergeant William Davidson

Sgt. Davidson became lost in the woods near St. Die, Germany, on October 25, 1944. A German patrol captured him. During his interrogation an artillery round fell nearby. Davidson took the opportunity to escape and headed south. Three weeks later he arrived at the Swiss border. He was taken into custody in Switzerland and put in a cell block with 60 German officers. When he was identified as an American, he was removed and returned to allied control.

Escape and Evasion Report Number 800 – Major Donald Willis

Maj. Willis’ plane was struck by anti-aircraft fire while flying over German occupied Holland. His plane crash-landed in the middle of a Dutch soccer game, scattering 500 players and spectators. After exiting the plane he began to leave the area under the confusion. He came upon a group of bicycles and a jacket; he took a bike and covered himself with the jacket. He began to ride down a road and passed an arriving German patrol. He spent the next several days sleeping in barns and haystacks. He accidently wandered into a German anti-aircraft battery and was shooed away by a soldier who thought he was a Dutch civilian.

Following instructions from civilians he began his attempt to make it to Brussels. In Antwerp he saw a bar with a sign advertising bock beer and went in and ordered a bock beer. The Belgian bartender guessed his identity and took him to a backroom and provided him with food. At Broom the only way to continue his journey was to cross a German-controlled bridge. He watched workers moving back and forth, carrying poles. Major Willis followed close behind some of the workers. When he got to the area across the bridge where the laborers were working, he discovered that they were working under watch of an armed German soldier.

Willis pretended to work along with the other men. Later an ice cream vendor with a cart arrived. While the workers were at the cart and the German soldier had his back turned, Willis walked off. Later a member of the Belgium underground recognized that he was an American and his passage out was arranged.

During their debriefings servicemen were asked if they knew about any others in enemy territory. Major Willis gave this account. “During my evasion while I was living in a large Belgian city I watched a . . . B-17 catch fire and leave formation. Soon after that several parachutes opened above the city and one floated down into the section of town where I was. I had a good view of it and watched this parachutist land in the walled-in garden of a house. Just as he touched the ground a German motorcyclist stopped in front of the house and ran around to clamber over the garden wall at the back. When the German got into the garden the American burst through the front door of the house and hopped on the German’s motorcycle and tore off down the street blowing his horn as loud as he could and cheered on by the Belgian people.”

Escape and Evasion Report Number 521 – Second Lieutenant Robert Laux

After parachuting over Amiens from the plane he was piloting Laux, a mail clerk from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, came across a French woodcutter who gave him civilian clothes. Laux headed south in an attempt to reach Spain. While walking down a road a German on a motorcycle stopped, raised his hand, and shouted ‘Halt!’ Laux said that he thought that the German was saluting him, so I gave him the Hitler salute back. Later a number of truckloads of Germans passed, he gave heil Hitler salutes to them all of them and they returned his salute.

The next day while Laux was looking at signs at a crossroads a German staff car full of heavily armed MP’s pulled up. Laux began to walk away when one German motioned for him to come over. The German said something to Laux in French which he could not understand. Laux said in his report that, “I looked dumb.” The German repeated what he said, this time slowly. Laux pointed down the road and car drove off. Further down the road Laux showed a French woman his phrase card and she hid him in a barn. The French Resistance then set him on an escape route.

Escape and Evasion Report Number 328 – Staff Sergeant William Howell

Tail Gunner Staff Sergeant William Howell from North Carolina, of the 533rd bomb squad was wounded from German fire when his plane came under attack. After bailing out he landed in the woods. He evaded several Germans in the woods and once slept behind a sentry. Howell was taken in by a French family. After giving him very much cognac to drink, their son pulled shrapnel from Howell’s hands, legs, and head. Howell stood at the couple’s home disguised as a boy scout and slept in a pup tent. Howell left for Spain after the French resistance arranged for his travel.

Escape and Evasion Report Number 904 – Second Lieutenant Eugene Squier

Co-pilot 2nd Lt. Eugene Squier, a dental technician in civilian life from San Francisco, California, was forced to parachute from his plane after it was hit on the way to bomb a railroad bridge at Nantes. After being aided by several civilians, two days after ditching, an elderly couple approached him as he was walking down a road. They asked him if he was an American flyer. They told him they had contacts. They hid him in their chicken coup and told him they feared that their neighbors were collaborators. He was later taken to a safe house; however plans for his return were not able to be made. Three weeks later he heard that the Americans had taken over a nearby town, so he set off by foot. On his way he tried to stop a passing transport of American troops, but they would not stop since he was wearing civilian clothes. The next day a Frenchman told him that there were 11 Germans looking for an American officer so they could surrender. When Squier approached the Germans they did not believe he was an American. They would not give up their weapons because they feared the French would seek reprisal. They surrendered their weapons after he finally convinced them that he was an American and the Germans were locked up in the town jail.