Vietnam War: Tet Offensive Cia – Defense – State Dept

$19.50

Description

The Tet Offensive: Timeline and Key Figures

Detailed Timeline of the Tet Offensive Events (1967-1968)

Mid-1967:

- Hanoi Leadership Decision: Against a backdrop of mounting war costs and no clear military victory for either side, the communist party leadership in Hanoi decides the time is ripe for a general offensive in rural areas combined with a popular uprising in the cities. The goals are to destabilize the Saigon regime and force the U.S. to negotiate.

- Planning the Offensive: Following the death of General Nguyen Chi Thanh, General Vo Nguyen Giap becomes the primary strategist for the offensive, reluctantly planning it under pressure from the Le Duan-dominated Politburo. The plan involves a three-phase approach: border attacks, attacks on major cities to spark an uprising, and then attacks on isolated foreign forces.

October 1967:

- Phase One Begins: The first stage of the Tet Offensive commences with small attacks in remote and border areas, aiming to draw ARVN and U.S. forces away from the cities.

- Increased Infiltration: The rate of North Vietnamese troop infiltration into South Vietnam rises significantly, reaching 20,000 per month by late 1967.

- U.S. Predictions: The United States command in Saigon predicts a major Communist offensive in early 1968, anticipating the DMZ area would be the primary target. Consequently, U.S. troops are deployed to strengthen northern border posts, and ARVN forces take over security in the Saigon area.

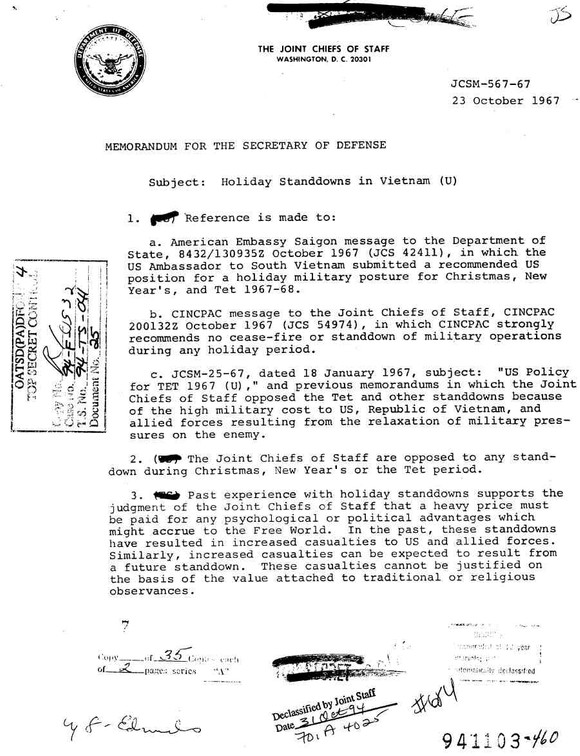

- Holiday Standowns: Memos within the U.S. military discuss plans for holiday standowns in October and December.

- North Vietnam Announces Truce: North Vietnam announces a seven-day truce for the Tet (Lunar New Year) holiday, from January 27 to February 3, 1968. The South Vietnamese army plans for recreational leave for a large portion of its forces.

Late January 1968:

- Relaxed Preparedness: Despite warnings of an impending offensive, the preparedness of both ARVN and the U.S. military is relatively relaxed due to the upcoming Tet holiday. Over half of ARVN forces are on leave.

- Khe Sanh Importance: A January 29 memo from General Westmoreland to President Johnson reiterates the importance of Khe Sanh.

- CIA Warning: By late January, some targets of the impending offensive have been identified by U.S. intelligence, and this information is communicated to senior military and political leaders in Saigon and Washington. Communications intelligence provides clear warnings of larger-than-ever attacks.

- January 31, 1968: Full-Scale Offensive Begins:Simultaneous Attacks: Communist forces launch simultaneous attacks on five major cities, thirty-six provincial capitals, sixty-four district capitals, and numerous villages across South Vietnam.

- Saigon Attacks: In Saigon, Viet Cong suicide squads attack key targets including the Independence Palace, the radio station, the ARVN’s joint General Staff Compound, Tan Son Nhut airfield, and the United States Embassy.

- U.S. Embassy Attack: Nineteen Viet Cong commandos attack the U.S. Embassy at 2:45 AM. They breach the compound wall but do not press their attack after initial casualties among their leadership. American reinforcements arrive, and the embassy compound is retaken by morning with all remaining Viet Cong killed.

- Widespread Collapse: Most of the initial attack forces throughout the country are pushed back within a few days, often due to U.S. bombing and artillery, causing significant urban damage.

- Battle of Khe Sanh Intensifies: A substantial assault is launched against the U.S. firebase at Khe Sanh, which had begun on January 21st. Three PAVN divisions surround the base. The battle involves heavy artillery bombardment, sporadic infantry attacks, and significant U.S. air support, including B-52 bombing. Ground supply to the base is cut off, relying on innovative air resupply methods.

February 1968:

- Battle of Hue (February 2-26):An estimated 12,000 Communist troops who had infiltrated Hue seize the city.

- They hold the city until late February, during which time approximately 2,000 to 3,000 officials, police, and others are executed as counterrevolutionaries (the Massacre at Hue).

- South Vietnamese Army and understrength U.S. Marine battalions (fewer than 2,500 men) counterattack and gradually fight to retake the city street by street and house by house.

- Heavy urban combat ensues, resulting in significant casualties for both sides and extensive damage to the historically and culturally significant city. Initially, U.S. air and artillery strikes are limited.

- The Citadel, a fortified section of Hue, is recaptured after four days of intense fighting.

- Casualty rates during the battle are exceptionally high, with U.S. Marine battalions experiencing daily wounded rates significantly higher than in previous high-intensity battles.

- U.S. Intelligence Assessment: A Combined Military Interrogation Center report, compiled on February 28, details information concerning sapper training and the attack on the US Embassy in Saigon based on a captured Viet Cong member’s interrogation.

- Congressional Medal of Honor Actions (February 21): Staff Sergeants Joe R. Hooper and Clifford C. Sims of the 101st Airborne Division distinguish themselves in the battle of Hue, both earning the Congressional Medal of Honor (Sims posthumously).

- CIA Assessment of Failure: A February 14 memo for Walt Rostow discusses the captured “Danang Document,” containing the Viet Cong’s assessment of the Tet Offensive’s failure.

- Intelligence Working Group Report (April 8): A working group comprising officers from various U.S. intelligence agencies prepares an interim report, “Intelligence Warning of the Tet Offensive in South Vietnam,” detailing the intelligence available prior to the offensive.

March 1968:

- Khe Sanh Siege Continues: The siege of Khe Sanh by PAVN forces continues, with heavy bombardment and air strikes.

- Policy Reassessment in Washington: The Tet Offensive sparks a major policy debate in Washington regarding troop levels and the overall U.S. strategy in Vietnam.

- President Johnson’s Announcement (March 31): In a televised address, President Lyndon B. Johnson announces he will not seek reelection, declares a partial halt to the bombing of North Vietnam, and calls for peace talks with Hanoi.

April 1968:

- Siege of Khe Sanh Ends (April 8): The PAVN breaks off their assault on Khe Sanh. Both sides claim the battle served its intended purpose.

May-August 1968:

- Continued Communist Attacks: Communist forces attempt to maintain momentum with a series of attacks, primarily targeting cities in the Mekong Delta, including a second assault on Saigon in May involving rocket attacks.

- Policy Focus on Negotiations: U.S. policy increasingly focuses on finding a negotiated end to the war, with diplomatic contacts explored with various countries and tentative prisoner of war contacts made. The search for a venue for peace talks with North Vietnam becomes a priority.

June 1968:

- 1st Cavalry Division Lessons Learned: The 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile) issues a lessons learned report on June 13, covering their deployment and operations during the Tet Offensive and subsequent battles, including the relief of Khe Sanh and operations in the A Shau Valley.

June 1969:

- Provisional Revolutionary Government (PRG): The National Liberation Front (NLF) and its allies form the Provisional Revolutionary Government of the Republic of South Vietnam (PRG), recognized by Hanoi as the legal government of South Vietnam. By this time, communist losses since the Tet Offensive are estimated at 75,000, and morale is faltering.

Cast of Characters

North Vietnamese/Viet Cong:

- General Vo Nguyen Giap: A leading North Vietnamese general, chief architect of the Viet Minh victory at Dien Bien Phu in 1954, and the primary strategist behind the Tet Offensive (though he claimed to have been against the idea initially). He favored guerrilla tactics but ultimately planned the large-scale conventional offensive.

- Nguyen Chi Thanh: A North Vietnamese general who preceded Giap in advocating for general main force action in the war. His death in 1967 led to Giap taking over strategic planning.

- Le Duan: The General Secretary of the Vietnamese Communist Party, who reportedly pushed for the Tet Offensive, overriding Giap’s preference for guerrilla warfare.

- Members of C-10 Bn: A Viet Cong battalion whose sappers were involved in the infiltration and attack on the U.S. Embassy in Saigon.

United States:

- Lyndon B. Johnson: The President of the United States during the Tet Offensive. The offensive significantly impacted his administration’s policy in Vietnam, leading to a reassessment of the war, a partial bombing halt, and his decision not to seek reelection.

- General William C. Westmoreland: Commander of the United States Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (COMUSMACV). His perspective on the war, troop requirements (including a later request for 200,000 more troops that was denied), and the importance of Khe Sanh are documented.

- Richard Helms: Director of Central Intelligence (DCI) during the Tet Offensive. He was informed of intelligence indicating potential attacks during Tet and communicated this to senior officials.

- Walt Rostow: Special Assistant for National Security Affairs to President Johnson. He received a memo concerning the captured “Danang Document” assessing the Tet Offensive’s failure.

- Clark Clifford: Initially Secretary of Defense McNamara’s successor. He headed a presidential commission that refused General Westmoreland’s request for additional troops, indicating a shift in the administration’s approach. His papers are a significant source of information.

- Robert McNamara: Served as Secretary of Defense at the beginning of 1968 and his files are important for understanding the context leading up to and during the Tet Offensive.

- Ambassador Averell Harriman: Involved in U.S. diplomatic efforts to explore peace negotiations with Hanoi. His papers related to these efforts are significant.

- Cyrus Vance: Worked with Ambassador Harriman on peace negotiation efforts in Paris.

- Ambassador Ellsworth Bunker: U.S. Ambassador to South Vietnam. His weekly reports to the President are a valuable source of information.

- George Carver: DCI’s Special Assistant for Vietnam, involved in intelligence analysis.

- Staff Sergeant Joe R. Hooper: Member of Company D, Second Battalion (Airborne), 501st Infantry, 101st Airborne Division. He was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor for his actions during the Battle of Hue.

- Staff Sergeant Clifford C. Sims: Member of Company D, Second Battalion (Airborne), 501st Infantry, 101st Airborne Division. He was posthumously awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor for his actions during the Battle of Hue.

- General William W. Momyer: Deputy for Air under General Westmoreland, appointed as single manager for air operations, a point of controversy during the Battle of Khe Sanh.

- LCDR Charles A. P. Turner: Author of a 2003 thesis analyzing American leadership and decision-making failures in the lead-up to the Tet Offensive.

- Commander G. Paul Kish: Author of a 1995 study analyzing the Tet Offensive from an operational perspective.

- LTC John R. Combs: Author of a 1995 study comparing Dien Bien Phu and the Tet Offensive in relation to Clausewitz’s theories.

- Major Charles W. Innocenti: Author of a 2002 monograph reviewing intelligence analysis techniques using the Battle of Hue as a case study.

- Commander Joseph W. Swaykos: Author of a 1996 paper analyzing the Tet Offensive from a North Vietnamese operational art perspective.

- Lieutenant Commander Nancy V. Kneipp: Author of a 1996 paper examining the Tet Offensive through the lens of the Principles of War.

South Vietnamese:

- General Cao Van Vien: Chief of the Joint General Staff of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN). He wrote the introduction to the South Vietnamese Army’s history of the Tet Offensive.

- Professor Mai: A professor at the University of Hue, interviewed by Walter Cronkite.

Media:

- Walter Cronkite: A prominent American news anchor for CBS, who interviewed Professor Mai of the University of Hue, reflecting the media coverage of the offensive.

This timeline and cast of characters provide a comprehensive overview of the main events and individuals mentioned within the provided source regarding the Vietnam War’s Tet Offensive.

Vietnam War: Tet Offensive Cia – Defense – State Dept – South Vietnamese Army Report

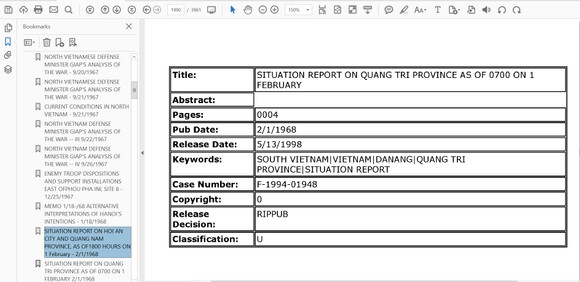

3,921 pages of CIA, Department of Defense, State Department files, South Vietnamese Army history, U.S. Army photos and South Vietnam Army photos covering the Vietnam War’s Tet Offensive. Material dates from 1967 to 2003.

In mid-1967 the costs of the Vietnam War mounted daily with no clear, complete military victory in sight for either side. Against this background, the communist party leadership in Hanoi decided that the time was ripe for a general offensive in the rural areas combined with a popular uprising in the cities. The primary goals of this combined major offensive and uprising were to destabilize the Saigon regime and to force the United States to opt for a negotiated settlement.

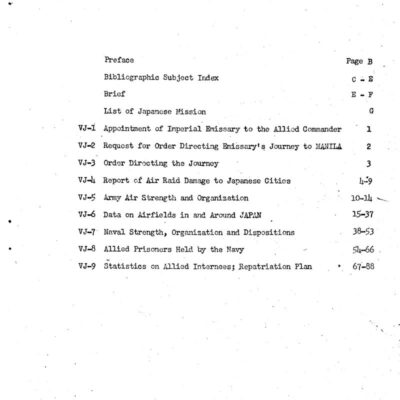

Documents in this collection include:

DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE FILES

After Action Report, The Battle of Hue, 2-26 February 1968

A 13-page after action report kept by the Command Historian of the United States Army, Vietnam of the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam.

Command History. United States Military Assistance Command, Vietnam 1968

1,236 pages in two volumes of the formally top-secret United States Military Assistance Command, Vietnam annual command history. Coverage include: Policy objectives, strategy, NVN Infiltration, NVN Political Infrastructure, Navy Operations, Pacification, Psychological Operations, GVN leadership, and outlook for 1969.

The objective of this history is to provide a comprehensive official record of operations and status of the command to include its many facets of activity viewed from the level of the commander, General William C. Westmoreland, with an account of the problems he faced and the decisions he made in solving them. Although it was not intended to duplicate unnecessarily the official histories of the component commanders, those operational matters as well as administrative and logistical problems have been covered which required the attention of COMUSMACV General William C. Westmoreland, in his capacity as the US operational commander and senior US military commander in the Republic of Vietnam.

Command History. United States Military Assistance Command, Vietnam 1968. Volume 1: This Volume contains Letter of Promulgation, Title Page, Preface, Table of Contents, List of Illustrations., (15 Index Pages). Following are: Chapter I – Introduction; Chapter II – The Strategy and the Goals; Chapter III – The Enemy; Chapter IV – Friendly Forces; Chapter V – Operations in the Republic of Vietnam; Chapter VI – Pacification and Nation Building. Immediately following each Chapter are numbered footnotes to the information contained, indicating the sources of information

Command History. United States Military Assistance Command, Vietnam 1968. Volume 2: This Volume contains Contents: Intelligence; Psychological Operations; Logistics; Research and Development; Contingency Plans and Special Studies; Special Problem Areas and Selected Topics; TET Offensive in Retrospect; Anti-Infiltration Barrier; Office of information and Press Relations and Problems; List of Ground Operations by Corps Tactical Zone; Commanders and Principal Staff Officers.

Saigon Embassy Infiltration Documents

36 pages of files from the U.S. Military Assistance Command Vietnam, Office of the Assistant Chief of Staff for Intelligence, Combat Intelligence Directorate. A Combined Military Interrogation Center interrogation report of Viet Cong who infiltrated the United States Embassy during the Tet Offensive 1968, compiled on February 28, 1968. This report contains information concerning sapper training and the attack on the US Embassy in Saigon by members of the C-10 Bn. In the PAVN and Viet Cong, the sappers were special operations soldiers who used infiltration, sabotage, and ambush to attack enemy forces. The information was provided by a captured member of the C-10 bn.

Material included in the report covers information on induction by the Viet Cong, basic training, political training, sapper training, training and planning for the January 31, 1968 infiltration of the US Embassy in Saigon, details of the attack and photos of the captured VC informant.

Lessons Learned, Headquarters, 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile)

A 74 page, June 13, 1968, lessons learned report. The report follows the completion of a major deployment of the 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile), from Binh Dinh Province and Southern I Corps Tactical Zone in late January 1968. This reporting period covers the initiation of high intensity combat operations in Quang Tri and Thua Thien Provinces. It encompasses three highly successful and tactically significant operations: (1) The Tet Offensive, which saw the 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile), prevent the seizure of Quang Tri and assisting in the expulsion of the NVA from their foothold in Hue City (Operation Jeb Stuart 1); (2) Operation PEGASUS/LAM SON 207A which relieved the NVA pressure on the 26th Marine Regiment at Khe Sanh; and (3) the entirely air-supported Operation DELAWARE/LAM SON 216, which disrupted NVA activities by means of a reconnaissance in force in the A Shau valley.

Congressional Medal of Honor Files

40 pages of files from the Army’s Adjutant General Section, Military Personnel Division, Awards Branch. These files depict the situation on 21 February 1968, at the battle of Hue, Republic of Vietnam, at which Staff Sergeant Joe R. Hooper and Staff Sergeant Clifford C. Sims, of Company D, Second Battalion (Airborne), 501st Infantry, 101st Airborne Division, both distinguished themselves. As a result, they were both awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor. Clifford C. Sims was award the medal posthumously. In an extraordinary occurrence, both Hooper and Simms of the same company earned the Congressional Medal of Honor on the same day. Documents include eyewitness statements, list of personnel in the immediate area saved, tactical situation diagrams, motivational analysis of actions and drafts of citations.

Other files include:

10 pages of memos from October and December 1967 concerning holiday standowns. A 2-page January 29, 1968 memo for President Johnson reiterating General Westmoreland’s view on the importance of Khe Sanh.

SOUTH VIETNAMESE ARMY HISTORY OF TET OFFENSIVE

A 1969, 480-page history with 30 diagrams and 246 photos, of the Tet Offensive published by the South Vietnamese Army, translated into English by the Army’s J5/JGS Translation unit. The Tet Offensive from the view of the Republic of Vietnam. According to the introduction, a group of military historians was dispatched to many areas of the Vietnam Republic to collect information and interview many of the central characters of the dramas that unfolded there during the Tet Offensive. Includes an introduction by General Cao Van Vien.

CIA FILES

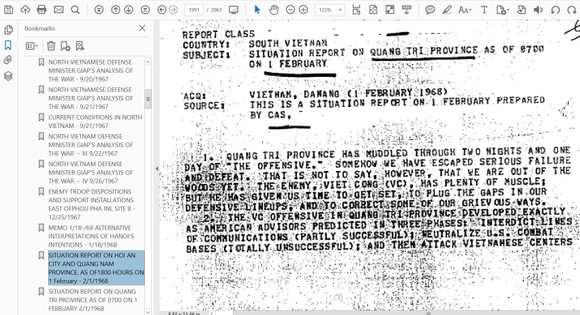

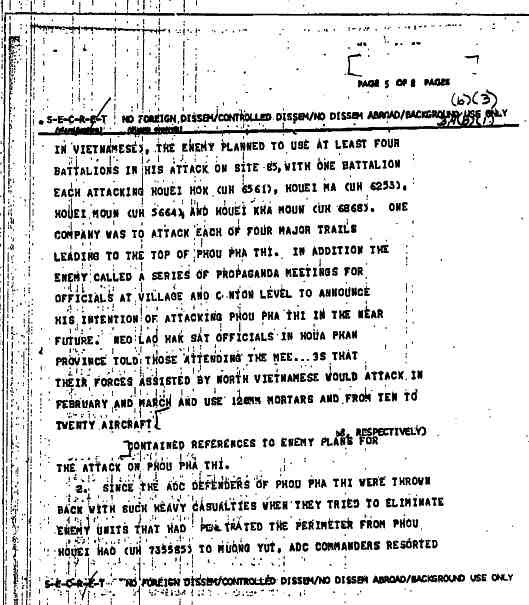

432 pages of CIA files related to the Tet Offensive. Files date from September 20, 1967 to July 17, 1969.

The U.S. intelligence community provided some forewarning of the coming general offensive in South Vietnam, although not comprehensive details. A working group of officers from the Central Intelligence Agency, Defense Intelligence Agency, Bureau of Intelligence and Research, National Security Agency, and Joint Staff prepared an interim report, entitled “Intelligence Warning of the Tet Offensive in South Vietnam,” April 8, 1968. Representatives of the group visited Vietnam March 16-23 to collect documents, receive briefings, and conduct interviews.

The working group report indicates that Director of Central Intelligence Richard Helms informed the President’s Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board in February that there had been evidence in January that attacks in the Highlands might be conducted during the Tet holiday. By late January, some targets had been identified, and the intelligence had been communicated to senior military and political leaders in both Saigon and Washington. The report continues: “Despite enemy security measures, communications intelligence was able to provide clear warning that attacks, probably on a larger scale than ever before, were in the offing. Considerable numbers of medium- and low-grade enciphered enemy messages were read…. They included references to impending attacks, more widespread and numerous than seen before. Moreover, they indicated a sense of urgency, along with an emphasis on thorough planning and secrecy not previously seen in such communications. These messages, taken with such nontextual indicators as increased message volumes and radio direction finding, served both to validate information from other sources in the hands of local authorities and to provide warning to senior officials.” The report concluded, however, that the evidence was “not sufficient to predict the exact timing of the attack.”

Other highlights include: September 1967 memos on North Vietnamese Army (NVA) General Vo Nguyen Giap’s statements concerning his analysis of the progress and future of the war. A January 18, 1968 CIA Office of National Estimates report to CIA director Richard M. Helms titled “Alternative Interpretations of Hanoi’s Intentions.” Various situation reports on the status of the Tet Offensive during its first few days. A February 14, 1968 memo for Walt Rostow, Special Assistant for National Security Affairs to President Johnson, concerning the captured “Danang Document”, giving the Viet Cong’s assessment of the failure of the Tet Offensive.

DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE REPORTS

224 pages of reports by the Department of Defense and reports commissioned by the Department of Defense.

An Analysis of the Psychological Necessity of Censorship in Combat Zones (1970)

The primary purpose of this 209-page study was to examine the historical evolution of news censorship in the United States, the current military information policy in Vietnam, and media performance in reporting selected crisis combat events of the Vietnam War, to determine the necessity of censorship in the area of combat operations during periods of low intensity warfare. A secondary purpose was to explore the psychological effects of established media performance on the national will to persist in this form of conflict. A content analysis was conducted of two combat actions, the Tet Offensive and Ap Bia Mountain (commonly referred to as Hamburger Hill), as reported in The New York Times, San Francisco Chronicles, and The Kansas City Star. First, the three criticisms of position reporting, uninformed reporting, and erroneous reporting, as indicated in previous research, were noted, and criteria within these areas were then postulated in an attempt to systematically analyze the news content.

The Battle for Hue: Casualty and Disease Rates During Urban Warfare

A 15-page August 1993 Naval Health Research Center report. Daily rates of casualty and illness incidence sustained in the re-taking of the city of Hue during the North Vietnamese Tet Offensive of 1968 were examined. The daily wounded rate for the U.S. Marine battalions involved was 17.5 per 1,000 strength, and ranged from 1.6 to 45.5. The killed-inaction rate per 1,000 strength per day was 2.2, and ranged from 0.0 to 9.6. The wounded rate during the urban warfare of Hue was three times higher than during the high intensity battle for Okinawa and six-fold the wounded rate during normal Marine operations at the peak of the Vietnam Conflict. The disease/nonbattle injury (DNBI) rate remained steady over the course of the Hue operation at approximately 1.0 per 1,000 strength per day. Report covers Casualty rates, Illness incidence, urban warfare, and medical planning.

DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE STUDIES

672 pages of military academic studies related to the Tet Offensive of the Vietnam War.

Air Power and the Fight for Khe Sanh

A 1986, 145-page narrative by the Office of Air Force History. This volume concentrates on the operations, activities, and accomplishments of the U.S. Air Force at Khe Sanh. Also included in this narrative is a discussion of several controversies and problem areas, which arose during the battle, such as General Westmoreland’s appointment of Gen. William W. Momyer, his deputy for air, as single manager for air operations.

American Leadership and Decision-Making Failures in the Tet Offensive

A 74-page, June 2003 thesis by LCDR Charles A. P. Turner. This thesis addresses the question of how the American leadership failed to assess correctly the indications of an impending offensive in the months preceding the 1968 Tet Offensive in Vietnam. The thesis analyzes and investigates the following weaknesses that contributed to the failure to foresee the Tet Offensive: North Vietnamese and Viet Cong deceptive actions, American inability to analyze those actions, measures the United States had in place to detect and to counter North Vietnamese preparations for the offensive, and the incomplete organization of the American intelligence organization in theater.

Obscuring Victory and Defeat. The Vietnamese Tet Offensive: An Operational Perspective.

A 27-page, 1995 study by Commander G. Paul Kish, United States Navy. This case study analyzes the role of operational art in irregular actions directed against American/South Vietnamese forces during the Tet Offensive of the early months of 1968.

Dien Bien Phu 1954, Tet Offensive 1968, and Clausewitz: An Analysis

A 13-page, 1995 study by LTC John R. Combs. This paper presents an analysis of Dien Bien Phu and the TET Offensive of 1968. The analysis is in response to a request by President Lyndon B. Johnson to get some clarification on any linkage between Dien Bien Phu and the TET Offensive, and the role of Carl von Clausewitz’s theories in explaining the two battles. The result is a comparative analysis between the French defeat at Dien Bien Phu in 1954 and the Tet Offensive of 1968 in South Vietnam. On the tactical level of war the two operations could not be more dissimilar. The former was an outright tactical defeat of a French strong point by the Vietminh, while the latter was a defeat of a large number of South Vietnamese Communists by U.S. Forces. However, it is on the strategic level of war, in support of strategic national policy formulation and execution, where the lessons of Dien Bien Phu and Tet 1968 merge.

Intelligence Analysis for Urban Combat

A 76-page, April 2002 monograph by Major Charles W. Innocenti, Military Intelligence. This study reviews the analytical techniques in four historic case studies to determine if applying these techniques would have identified indicators of enemy course of actions. The four case studies were the battle for Hue in 1968, the US Marine involvement in Beirut from 1982-1984, and the battles for Grozny in 1995 and in 1999.

Operational Art in the Tet Offensive – A North Vietnamese Perspective

A 23-page, June 1996 paper by Commander Joseph W. Swaykos, United States Navy. The author writes that the Vietnam War’s Tet Offensive provides an excellent example of the successful application of operational art when viewed from the North Vietnamese perspective. Operational leadership was exercised by General Vo Nguyen Giap as he assured that the offensive served as an extension of North Vietnamese strategic objectives and desired end state. Giap developed and executed an operational design that fully accounted for the centers of gravity and critical strengths and weaknesses of his forces and his enemy’s. While he suffered tactical defeats, Giap achieved nearly all of his operational objectives and his desired operational end state, delivery of a military shock to his enemy. The offensive ultimately lead to achievement of North Vietnam’s strategic objective and desired end state.

The Tet Offensive and the Principles of War

A 28-page, June 1996 paper by Lieutenant Commander, Nancy V. Kneipp, United States Navy. The author presents that although not a decisive operational success, the Tet Offensive is the acknowledged turning point of the Vietnam War. Using the Principles of War as a framework, we can gain insight into the cultural, operational and situational factors that affected the North Vietnamese planning strategies and execution realities and led to this result. Although the Communists considered the Principle of War when they planned this major operation, execution of the plan revealed weaknesses in a number of areas. These weaknesses were due, in large part, to North Vietnamese cultural bias and perceptions. Understanding the impact of these factors on the planning and execution of military operations is increasingly important in the context of today’s multinational coalitions, non-traditional adversaries, and military operations other than war.

Other study titles include: How the North Vietnamese Won the War-Operational Art Bends But Does Not Break in Response to Asymmetry, Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (ISR) Support to Urban Operations and Mission Analysis During Future Military Operations on Urbanized Terrain.

U.S. ARMY PHOTOS

17 U.S. Army photos of Tet Offensive related events. 246 photos taken by the South Vietnamese Army can be found in the section: HISTORY OF TET OFFENSIVE SOUTH VIETNAMESE ARMY HISTORY OF TET OFFENSIVE

FOREIGN RELATIONS OF THE UNITED STATES

689 pages of text transcriptions of the Foreign Relations, Vietnam, January-August 1968.

Produced by the Department of State, the Foreign Relations of the United States series presents the official documentary historical record of major U.S. foreign policy decisions and significant diplomatic activity. The series is produced by the State Department’s Office of the Historian. Foreign Relations volumes contain documents from Presidential libraries, Departments of State and Defense, National Security Council, Central Intelligence Agency, Agency for International Development, and other foreign affairs agencies as well as the private papers of individuals involved in formulating U.S. foreign policy.

This volume is part of a sub-series of volumes of the Foreign Relations series that documents the most important issues in the foreign policy of the 5 years (1964–1968) of the administration of Lyndon B. Johnson. The sub-series present in 34 volumes a documentary record of major foreign policy decisions and actions of President Johnson’s administration. This volume documents U.S. policy toward Vietnam from January to August 1968.

The editor of the volume sought to present documentation that explained and illuminated the major foreign policy decisions on Vietnam of the President, as counseled by his key foreign policy advisers. The documents include memoranda and records of discussions that set forth policy issues and options and show decisions or actions taken. The emphasis is on the development of U.S. policy and on major aspects and repercussions of its execution rather than on the details of policy execution.

President Lyndon Johnson relied upon his principal foreign policy advisers, Secretary of State Rusk, Secretary of Defense McNamara (and his successor Secretary of Defense Clifford), Assistant to the President Rostow, and many other official and unofficial advisers for counsel and recommendations on Vietnam policy. Because the editor’s primary focus was on the policy process of recommendation, discussion, and then final decision by the President, the locus of the volume is Washington, but it also covers events and developments in South Vietnam, as they affected the policy process.

The volume contains a number of major themes. Of primary importance to President Johnson were his and the Department of State’s continuing efforts to find a negotiated end to the war. The volume covers U.S. diplomatic contacts with Romania, Norway, and the Vatican to explore possible negotiation formulas with Hanoi in the hopes that they would lead to formal peace negotiations. Also covered are continued tentative prisoner of war contacts with the National Liberation Front in the hopes that they might lead to a separate political settlement. These diplomatic efforts were overshadowed by another major theme of the volume, the Tet Offensive and the resulting policy debate in Washington on whether to raise the number of U.S. troops in Vietnam. This debate led to a broader reassessment of U.S. policy in Vietnam, which culminated in the President’s order for a partial bombing halt of North Vietnam, his decision not to run for reelection, and an announcement of U.S. willingness to meet anywhere to negotiate peace. The search for a venue for the talks and attempts by advisers to convince the President to institute a full bombing halt comprise the final focus of the volume. Two other themes are evident in the volume, yet they are captured in only a few documents: the growing anti-war movement in the United States and the upcoming presidential elections of 1968. These two events affected discussions within the Johnson administration.

The editors of the Foreign Relations series have complete access to all the retired records and papers of the Department of State: the central files of the Department; the special decentralized files (“lot files”) of the Department at the bureau, office, and division levels; the files of the Department’s Executive Secretariat, which contain the records of international conferences and high-level official visits, correspondence with foreign leaders by the President and Secretary of State, and memoranda of conversations between the President and Secretary of State and foreign officials; and the files of overseas diplomatic posts. All the Department’s indexed central files for these years have been permanently transferred to the National Archives and Records Administration at College Park, Maryland (Archives II). Many of the Department’s decentralized office (or lot) files covering this period, which the National Archives deems worthy of permanent retention, have been transferred or are in the process of being transferred from the Department’s custody to National Archives II.

The editors of the Foreign Relations series also have full access to the papers of President Johnson and other White House foreign policy records. Presidential papers maintained and preserved at the Presidential libraries include some of the most significant foreign affairs-related documentation from the Department of State and other Federal agencies including the National Security Council, the Central Intelligence Agency, the Department of Defense, and the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

In preparing this volume, the editor made extensive use of Presidential papers and other White House records at the Lyndon B. Johnson Library. The large Vietnam Country File within the National Security File was one of the most important sources. Other useful components of the National Security File were the NSC History File, the Files of Walt Rostow, and Memoranda to the President. For Johnson’s meetings on Vietnam, the Tom Johnson Notes were the most valuable collection, although Meeting Notes Files were also useful. The Johnson tape recordings, of both telephone conversations and meetings in the Cabinet Room, were another key source from the Johnson Library. Other Johnson Library collections cited less frequently but still of value were the Office Files of White House aides, such as Harry McPherson and George Christian, and the Papers of Clark Clifford, George Elsey, and General William Westmoreland.

Second in importance to the records at the Johnson Library were the central files of the Department of State. Documents relating to the various peace initiatives are filed in POL 27-14 VIET or POL 27-14/[negotiating track code-name]. For example, POL 27-14 VIET/CROC is the repository for Ambassador Harriman’s initial peace negotiations documentation. Basic reporting and recommendations on important developments in South Vietnam were often put in POL 27 VIET S, the file reserved for military operations, but used as a catchall. It was the most important Department of State Central File. Of the Department of State lot files, the A/IM Files of Harriman and Cyrus Vance in Paris, Lot 93 D 82, were the most important. The IS/OIS files relating to the records of the Paris Peace Conference, Lot 90 D 345, and the IS/OIS files of Ambassador Bunker’s weekly reports to the President, Lot 92 D 306, were also valuable. The files of Ambassador at Large Averell Harriman, S-AH Files, Lot 71 D 461 are also important.

Of the records at the Department of Defense, which are at the Washington National Records Center, official files of Secretaries Robert McNamara and Clark Clifford, were significant: McNamara/OSD Files, FRC 330 71 A 3470, and the Clifford/OSD Files, FRC 72 A 2457-2468 and FRC 73 A 1250. The official records of the Joint Chiefs of Staff were also valuable. In addition, the files of Military Assistance Command, Vietnam at the Institute of Military History and the Westmoreland and Creighton Abrams Papers at the Center for Military History, contained useful information.

At the Library of Congress, Manuscript Division, the two most important collections for the volume were the Averell Harriman and Paul Nitze Papers.

For intelligence issues, DCI (Helms) Files, the DCI Executive Registry Subject Files and the Files of DCI’s Special Assistant for Vietnam, George Carver, at the Central Intelligence Agency, were most useful. The National Security Council’s Intelligence Files provided papers submitted to the 303 Committee and records of the Committee’s meetings.

The collection contains a text transcript of all recognizable text embedded into the graphic image of each page of each document, creating a searchable finding aid. Text searches can be done across all files in the collection.

About the Tet Offensive

The plan for the Tet Offensive originated in 1967, following the death of North Vietnamese General Nguyen Chi Thanh. The primary strategist was Thanh’s successor, General Vo Nguyen Giap. North Vietnamese Army (NVA) General Vo Nguyen Giap, was the chief architect of the Viet Minh victory over the French at Dien Bien Phu in 1954. Although Giap claimed afterward to have been against the idea, planning it “reluctantly under duress from the Le Duan dominated Politburo.” Giap had long advocated primarily using guerrilla tactics against the U.S. and South Vietnam, whereas Thanh had supported general main force action. Overriding Giap, the North Vietnamese leadership decided that the time was ripe for a major conventional offensive. They believed that the South Vietnamese government and the U.S. presence were so unpopular in the South, that a broad-based attack would spark a spontaneous uprising of the South Vietnamese population, which would enable the North to sweep to a quick, decisive victory.

To this end, a multiphase plan was developed: in the first phase, the People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN) would launch attacks on the border regions of South Vietnam to close those regions to American observation. Following this, a second phase of widely dispersed attacks by the Viet Cong directly into the major centers of the country would cause the collapse of the government and would prod the civilians into full-fledged revolt. With the government overthrown, the Americans and other allied forces would have no choice but to evacuate, leading to phase three attacks by the Viet Cong and PAVN against elements of the isolated foreign forces.

In October 1967, the first stage of the Tet Offensive began with a series of small attacks in remote and border areas designed to draw the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) and United States forces away from the cities. The rate of infiltration of troops from the North rose to 20,000 per month by late 1967, and the United States command in Saigon predicted a major Communist offensive early the following year. The DMZ area was expected to withstand the worst of the attack. Accordingly, United States troops were sent to strengthen northern border posts, and the security of the Saigon area was transferred to ARVN forces.

In the days immediately preceding the Tet Offensive, the preparedness of both the ARVN and the U.S. military were relatively relaxed. Despite warnings of the impending offensive, in late January more than one-half of the ARVN forces were on leave because of the approaching Tet (Lunar New Year) holiday. North Vietnam had announced in October that it would observe a seven-day truce from January 27 to February 3, 1968, in honor of the Tet holiday, and the South Vietnamese army made plans to allow recreational leave for a large part of its force.

On January 31, 1968, the full-scale offensive began, with simultaneous attacks by the communists on five major cities, thirty-six provincial capitals, sixty-four district capitals, and numerous villages. In Saigon, suicide squads attacked the Independence Palace (the residence of the president), the radio station, the ARVN’s joint General Staff Compound, Tan Son Nhut airfield, and the United States Embassy, causing considerable damage and throwing the city into turmoil. Most of the attack forces throughout the country collapsed within a few days, often under the pressure of United States bombing and artillery attacks, which extensively damaged the urban areas.

The attack against the U.S. Embassy was especially significant in the public’s perception of the U.S. military’s control over the situation. At 2:45 AM on January 31, nineteen Viet Cong commandos attacked the embassy. Although VC attacks had been taking place in Saigon for over an hour, the guards at the embassy had not been informed of this and had not been reinforced. The Viet Cong blew a hole in the embassy compound’s wall, killed several MPs, and entered the grounds. The few remaining American guards withdrew into the embassy building and locked the doors. Although the Viet Cong had an ample supply of explosives, they did not press their attack. Both officers in charge of the Viet Cong squad had been killed in the initial assault and the remaining guerrillas milled aimlessly around the grounds. Eventually American reinforcements arrived, and in the morning, six hours after the attack began, MPs retook the embassy compound, killing all of the remaining Viet Cong.

The offensive involved simultaneous military action in most of the larger cities in South Vietnam and attacks on major U.S. bases, with particular efforts focused on the cities of Saigon and Hue. Concurrently, a substantial assault was launched against the U.S. firebase at Khe Sanh. The Khe Sanh assault drew North Vietnamese forces away from the offensive into the cities, but North Vietnam considered the attack necessary to protect their supply lines to the south.

The Battle of Hue was perhaps the bloodiest battle of the Vietnam War, Lasting 26 days. Hue, which had been seized by an estimated 12,000 Communist troops who had previously infiltrated the city, remained in communist hands until late February. A reported 2,000 to 3,000 officials, police, and others were executed in Hue during that time as counterrevolutionaries. The South Vietnamese Army and three under strength U.S. Marine battalions, consisting of fewer than 2,500 men, attacked and soundly defeated more than 10,000 entrenched enemy troops, liberating Hue for South Vietnam.

The city of Hue was attacked by ten PAVN battalions and six Viet Cong battalions and almost completely overrun. Thousands of civilians believed to be potentially hostile to Communist control, including government officials, religious figures, and expatriate residents, were executed in what became known as the Massacre at Hue. The city was not recaptured by the U.S. and ARVN forces until the end of February. Due to the historical and cultural value of the city, the U.S. did not apply air and artillery strikes as widely as in other cities, at least initially. Instead, U.S. Marines of the 1st Marine Division and several Army units had to clear the city street by street and house by house; a deadly form of combat the U.S. military had hardly seen since WWII, and for which the soldiers were not trained. Over most of February, they gradually fought their way towards the Citadel, a fortified 3-square-mile section of the city, which was recaptured from PAVN troops after four days of struggle. The U.S. lost 216 men and the ARVN 384. The allies estimated the PAVN lost 8,000 in the city and in fighting in the surrounding area.

The extent of the massacre of civilians by the Communists was only realized over the following months and years, with the last mass graves being found in 1970. Approximately 2,800 bodies were found, and another 2,000 persons were missing. Some thousands of additional lives were lost from civilians being caught in the crossfire of the battle.

The Battle of Khe Sanh was perhaps the longest battle of the Vietnam War. Khe Sanh was an airstrip and U.S. Marine base just south of the DMZ. According to North Vietnam leadership, the attack on Khe Sanh, which began on January 21, was intended to serve two purposes: As a diversionary tactic to draw American attention and forces away from the upcoming Tet Offensive attacks, and to prevent the forces at Khe Sanh from attacking supplies and troops moving south on the Ho Chí Minh Trail. In turn, American military stated that the very purpose of the Khe Sanh base was to provoke the North Vietnamese into focused and prolonged battle, allowing American artillery and air strikes to inflict massive casualties.

Three PAVN divisions, totaling approximately 20,000 men, surrounded the Khe Sanh base and its 6,000 men. Throughout the battle, which lasted until April 8, the Marines were subjected to heavy artillery bombardment, combined with sporadic small-scale infantry attacks. There was never any major ground assault on the base, and the battle was largely a duel between American and PAVN gunners, combined with air strikes from the American side. American air support eventually included massive bombing by B-52s to destroy PAVN trenches and bunkers. Ground supply to the base was cut off, and airborne re-supply became difficult due to enemy fire. Thanks to innovative, high-speed “supply assaults” using fighter-bombers in combination with helicopters, air supply was never halted.

American media covered the battle extensively and often made pessimistic comparisons to the Battle of Dien Bien Phu, where a French base had been besieged and ultimately defeated by the Vietnamese in the 1946-1954 Indochina War.

In the end, the PAVN broke off their assault, and both sides would claim that the battle had served its intended purpose. The United States claimed 8,000 PAVN dead and considerably more wounded, against 205 American lives lost. As with the Vietnam War in general, the loss of American lives left a much greater impression upon the American public than with a military victory that could only be measured in terms of “kill ratio.” The fact that the Khe Sanh base was abandoned on June 23 of 1968, having been deemed of no further military value, inevitably encouraged this sense of futility about the battle and the overall war.

The Tet Offensive was a tactical defeat for the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese forces. The Tet Offensive is widely viewed as a turning point in the war despite the high cost to the communists (approximately 32,000 killed and about 5,800 captured) for what appeared at the time to be small gains. Although they managed to retain control of some of the rural areas, the communists were forced out of all of the towns and cities, except Hue, within weeks. Nevertheless, the offensive emphasized to the Johnson administration that victory in Vietnam would require a greater commitment of men and resources than the American people were willing to invest. On March 31, 1968, Johnson announced that he would not seek his party’s nomination for another term of office, declared a halt to the bombing of North Vietnam (except for a narrow strip above the DMZ), and urged Hanoi to agree to peace talks. In the meantime, with U.S. troop strength at 525,000, a presidential commission headed by the new United States secretary of defense, Clark Clifford, refused a request by General Westmoreland for an additional 200,000 troops.

Following the Tet Offensive, the communists attempted to maintain their momentum through a series of attacks directed mainly at cities in the delta. A second assault on Saigon, complete with rocket attacks, was launched in May. Through these and other attacks in the spring and summer of 1968, the Communists kept up pressure on the battlefield in order to strengthen their position in a projected a series of four-party peace talks scheduled to begin in January 1969 (that called for representatives of the United States, South Vietnam, North Vietnam, and the National Liberation Front to meet in Paris. In June 1969, the NLF and its allied organizations formed the Provisional Revolutionary Government of the Republic of South Vietnam (PRG), recognized by Hanoi as the legal government of South Vietnam. At that time, communist losses dating from the Tet Offensive numbered 75,000, and morale was faltering, even among the party leadership.

Walter Cronkite of CBS interviewing Professor Mai of the University of Hue. United States Army Photo

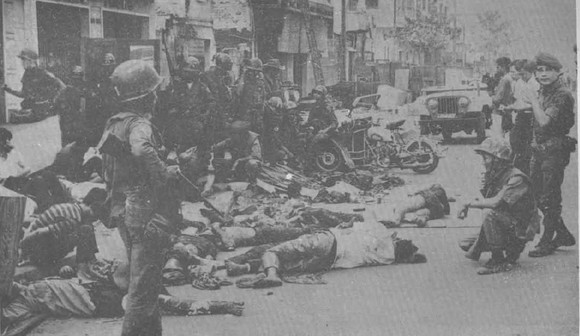

“Communist bodies in the Van Hanh Street after the Feb. 8 battle”, from South Vietnamese Army History of Tet Offensive

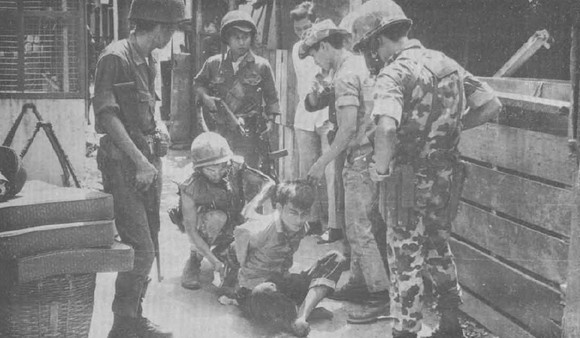

“A VC prisoner taken on Trieu Da Street” from South Vietnamese Army History of Tet Offensive

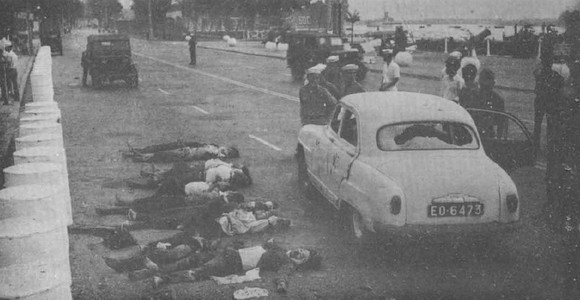

“All Viet Cong troops taking part in the assault on the Navy Headquarters were killed. This photo taken on 31 January 1968 show some ten VC bodies and the car they had used to come to their death row.” from South Vietnamese Army History of Tet Offensive

“VC sappers killed by Airborne troops in front of the Radio station.” from South Vietnamese Army History of Tet Offensive

Related products

-

Trial Notes of Ralph G. Albrecht, Prosecutor at the Nuremberg Trials of World War II

$3.94 Add to Cart -

Operation POPEYE in the Vietnam War

$5.94 Add to Cart -

Civil War Ulysses S. Grant’s Aide de Camp Orville E. Babcock’s Diaries & Court Documents

$3.94 Add to Cart -

Japan’s Surrender Documents from World War II

$1.99 Add to Cart