Tokyo Rose: Department of Justice Prosecution Files

$19.50

Description

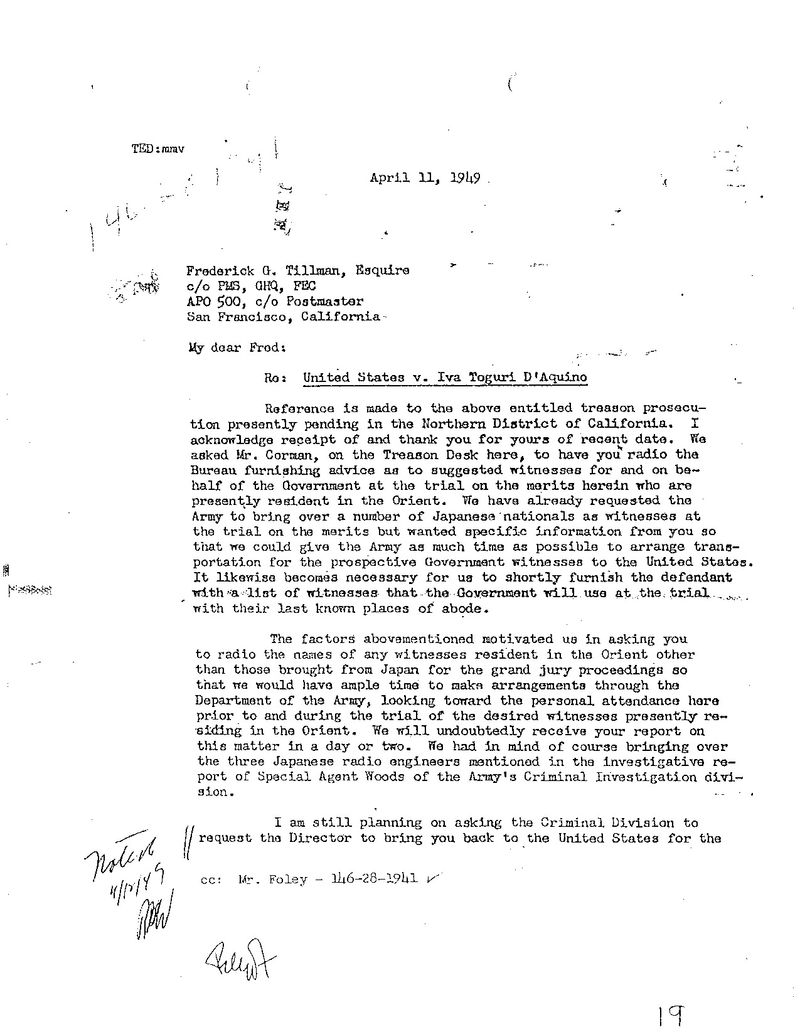

This extensive collection of 700 pages of Department of Justice files, spanning from June 1946 to February 1967, details the legal proceedings against Iva Toguri D’Aquino, infamously known as “Tokyo Rose.” The documents encompass the entire legal battle, from initial investigations to the final court decisions. They include a wealth of information on the legal strategies employed, the progression of the case through the judicial system, testimony from witnesses who appeared in court, and analysis of the content of the infamous “Zero Hour” radio broadcasts.

The moniker “Tokyo Rose” wasn’t a single individual but rather a collective term used by American servicemen to describe several women who broadcast English-language propaganda during World War II, each using various pseudonyms.

Following the war’s conclusion, two American journalists, Henry Brundidge and Clark Lee, embarked on a quest to identify the elusive “Tokyo Rose.” Their investigation ultimately led them to Iva Toguri D’Aquino. These reporters, in pursuit of a scoop, offered Ms. D’Aquino payment in exchange for an exclusive interview. She accepted their proposal, signing a contract that explicitly labeled her as “Tokyo Rose.” This interview, despite the reporters’ failure to honor their financial agreement, cemented D’Aquino’s public image as the primary “Tokyo Rose,” a perception that contrasted with the lack of such identification by Army or FBI investigators at the time. Subsequently, in September 1945, following media reports identifying D’Aquino as “Tokyo Rose,” U.S. Army authorities apprehended her. Iva Ikuko Toguri D’Aquino, born in Los Angeles to Japanese immigrants on July 4, 1916, and passed away on September 26, 2006, had a life significantly shaped by her dual heritage and the tumultuous events of World War II. She pursued higher education, graduating from UCLA with a zoology degree in 1940. Her journey to Japan in 1941, however, marked a turning point. Departing from San Pedro without the necessary travel document, she later offered justifications for her trip: a family matter involving a sick relative and aspirations to study medicine. This seemingly personal journey took on a far more complex dimension when she attempted to rectify her passport situation with the U.S. Vice Consul in Japan, expressing her desire to return home permanently. The bureaucratic process, however, was interrupted by the catastrophic events of Pearl Harbor.

The attack on Pearl Harbor drastically altered the circumstances surrounding Toguri’s situation. Many Japanese Americans residing in Japan chose to relinquish their U.S. citizenship to avoid potential persecution under the Imperial Japanese regime. In a powerful act of defiance, Toguri refused to renounce her citizenship, a den that would have significant consequences. Interestingly, the Japanese authorities did not consider her a threat and allowed her to remain free, likely recognizing her ability to support herself.

Her employment history during the war years provides further insight into her life in occupied Japan. For a period spanning from mid-1942 to late 1943, she worked as a typist for the Domei News Agency, a Japanese news organization. Later, in August 1943, she secured a position as a typist at Radio Tokyo, a role that required her English fluency. This seemingly innocuous employment would later become a focal point in the controversial events that followed. During World War II, Axis powers employed a cruel tactic: forcing Allied prisoners of war to create propaganda broadcasts. One such program, the infamous “Zero Hour” on Radio Tokyo, exemplifies this grim reality. Iva Toguri, later known as “Tokyo Rose,” was compelled to participate in this program. She wasn’t the sole perpetrator; a significant portion of the production team consisted of captured Allied personnel.

Specifically, an Australian army officer, Major Charles Cousens, a pre-war broadcasting professional captured during the fall of Singapore, was forced, through torture and coercion, to oversee the technical aspects of “Zero Hour.” This wasn’t simply a matter of reading news; it was a calculated Japanese psychological operation intended to undermine the morale of American forces.

The broadcasts, lasting 75 minutes, blended news reports with entertainment segments. Toguri’s role involved reading scripts crafted by Allied prisoners of war, including Major Ted Ince (an American) andtenant Normando Ildefonso “Norman” Reyes (a Filipino). These scripts, cleverly written, often contained subtle double meanings and innuendo, a testament to the ingenuity and resistance of the captive writers.

Over time, Toguri’s involvement evolved. By late 1944, she was contributing her own written content. Her compensation, a meager 150 yen per month (roughly $7 USD at the time), hardly reflects the gravity of her situation and the psychological pressure she faced.

Her personal life intersected with these events. In April 1945, she married Felipe Aquino. However, this marriage would soon become entangled in the post-war accusations against her.

The post-war period saw a dramatic shift in Toguri’s circumstances. Following the war’s end, sensationalized press reports wrongly identified Aquino as “Tokyo Rose,” leading to her arrest by U.S. Army authorities in September 1945. A thorough investigation ensued, involving the FBI and the Army’s Counterintelligence Corps. Despite the initial media frenzy, a lack of sufficient evidence led to her release in October 1945. A subsequent Justice Department document in 1946 officially declared the identification of Toguri as “Tokyo Rose” to be inaccurate. This highlights the complexities of the case and the challenges of separating fact from wartime propaganda and post-war sensationalism. As Iva Toguri D’Aquino began the process of returning to the United States, a significant backlash arose. Veteran organizations and influential broadcaster Walter Winchell spearheaded a movement to prevent her repatriation, demanding she face treason charges.

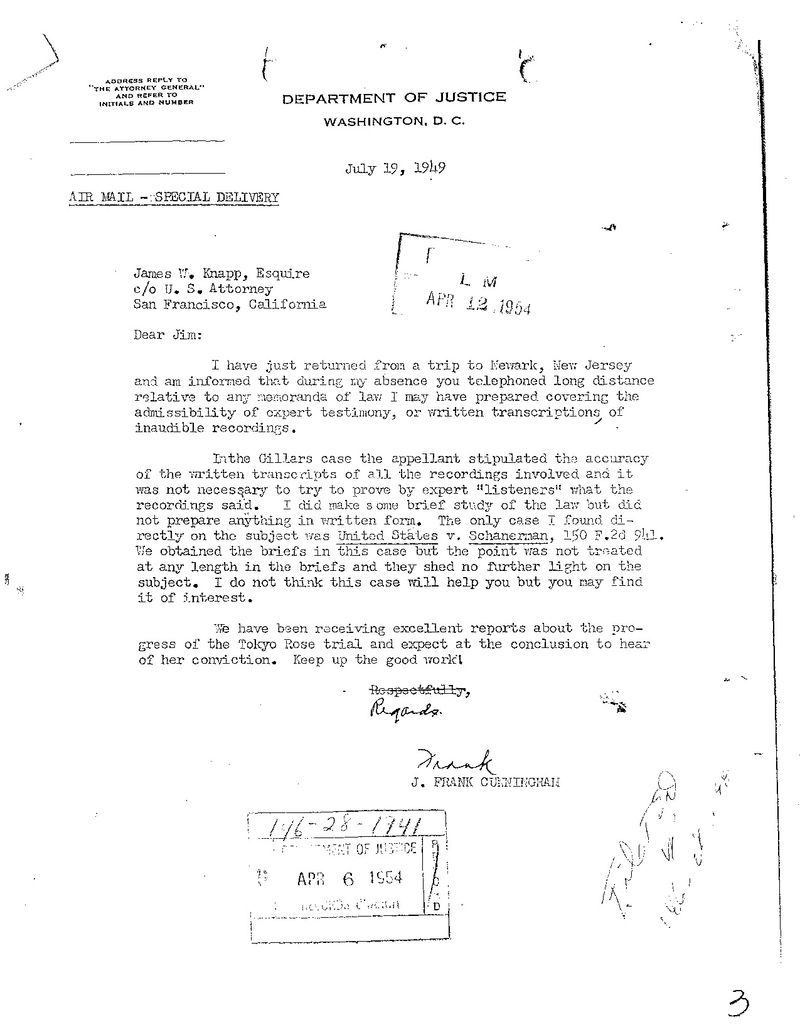

The Department of Justice subsequently revisited the case, diligently seeking grounds to prosecute her for treason. Their investigation involved sending a legal representative and journalist Harry Brundidge to Japan to gather testimony. Brundidge’s actions, however, involved questionable tactics, inducing a former acquaintance to commit perjury. This newly obtained evidence, along with other witness accounts, led the U.S. Attorney in San Francisco to convene a grand jury, resulting in eight charges against Aquino. She was then transported back to the United States under military guard, arriving in San Francisco on September 25, 1948.

Aquino’s trial commenced on July 5, 1949, the day after her 33rd birthday. The jury delivered a verdict on September 29, 1949, finding her guilty on a single count of treason. Subsequently, on October 6, 1949, she received a ten-year prison sentence and a $10,000 fine. After serving six years and two months at the Federal Reformatory for Women in Alderson, West Virginia, she was released on January 28, 1956. She successfully challenged government attempts to deport her and returned to Chicago.

Years later, in 1974, journalistic investigations revealed that key witnesses had recanted their testimony, claiming they had been coerced into lying under oath. This led to a presidential pardon granted by Gerald Ford in 1977, making Iva Toguri D’Aquino the only individual convicted of treason in the United States to ever receive such clemency. The released documents offer a multifaceted view of the case surrounding the individual known as Aquino. A key finding is a memo from the Assistant Attorney General declaring that Aquino was not guilty of any crime. This suggests a formal legal assessment cleared Aquino of wrongdoing. Furthermore, the documents detail the investigative process, specifically the search for individuals who could provide testimony. This highlights the effort expended to gather evidence, both for and potentially against Aquino. A particularly significant piece of evidence is an 8th of June 1949 report revealing a witness recanted their grand jury testimony against Aquino, claiming it was false. This casts serious doubt on the reliability of the case built against Aquino. Beyond the core legal aspects, the documents also reveal public sentiment, showcasing letters from concerned citizens protesting the repatriation of “Tokyo Rose” to the United States. This illustrates the broader societal context and the emotional impact of the case on the public. Finally, internal government memos from the late 1960s document attempts to recover $10,000 in outstanding fines, indicating a lingering financial aspect to the matter long after the main legal proceedings had concluded. The collection of these diverse materials paints a comprehensive picture, going beyond a simple legal record to encompass public opinion and administrative follow-up.

Timeline of Main Events in the Iva Toguri D’Aquino Case:

Pre-War:

- July 4, 1916: Iva Ikuko Toguri is born in Los Angeles, California, to Japanese immigrant parents.

- 1940: Toguri graduates from the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA) with a degree in zoology.

- July 5, 1941: Toguri travels to Japan to visit a sick aunt and study medicine.

- September 1941: Toguri applies for a U.S. passport at the U.S. Consulate in Japan, intending to return to the United States permanently.

World War II:

- December 7, 1941: Japan attacks Pearl Harbor; the United States declares war on Japan. Toguri’s passport application is delayed due to the outbreak of war.

- Mid-1942 – Late 1943: Toguri works as a typist for the Japanese Domei News Agency.

- August 1943: Toguri begins working as a typist for Radio Tokyo.

- November 1943: Toguri is recruited to participate in “The Zero Hour,” a Radio Tokyo program aimed at U.S. troops.

- Late 1944: Toguri begins writing her own material for “The Zero Hour.”

- April 19, 1945: Toguri marries Felipe Aquino, a Portuguese citizen of Japanese-Portuguese ancestry.

Post-War:

- September 1945: American reporters Henry Brundidge and Clark Lee identify Toguri as “Tokyo Rose” and secure an exclusive interview, but fail to pay her as agreed. U.S. Army authorities arrest Toguri.

- October 1945: After investigation, authorities deem the evidence against Toguri insufficient and release her.

- September 24, 1946: The Assistant Attorney General concludes that Toguri did not commit a crime.

- 1948: Veteran groups and broadcaster Walter Winchell launch a campaign demanding Toguri’s prosecution.

- September 25, 1948: Toguri is indicted on eight counts of treason and brought to San Francisco under military escort.

- July 5, 1949: Toguri’s trial begins.

- September 29, 1949: The jury convicts Toguri on one count of treason.

- October 6, 1949: Toguri is sentenced to ten years in prison and fined $10,000.

- January 28, 1956: Toguri is released from the Federal Reformatory for Women in Alderson, West Virginia, after serving six years and two months of her sentence.

- Late 1960s: The U.S. government attempts to collect the $10,000 fine.

- 1974: Investigative journalists uncover evidence that key witnesses against Toguri were coerced into perjury.

- 1977: President Gerald Ford pardons Toguri.

- September 26, 2006: Iva Toguri D’Aquino dies.

Cast of Characters:

Iva Ikuko Toguri D’Aquino (1916-2006): American citizen of Japanese descent, born and raised in Los Angeles. Central figure in the “Tokyo Rose” case. Worked for Radio Tokyo during World War II, broadcasting English-language propaganda under various aliases. Wrongfully convicted of treason in 1949, she was pardoned in 1977.

Henry Brundidge: American reporter who, along with Clark Lee, identified Toguri as “Tokyo Rose” and secured an exclusive interview with her. Played a role in securing perjured testimony against Toguri, leading to her indictment.

Clark Lee: American reporter who worked with Brundidge in identifying Toguri and obtaining an interview.

Major Charles Cousens: Australian prisoner of war and former broadcaster who was forced by the Japanese to produce “The Zero Hour.”

Major Ted Ince: American prisoner of war who wrote scripts for “The Zero Hour.”

Lieutenant Normando Ildefonso “Norman” Reyes: Filipino prisoner of war who worked on “The Zero Hour.”

Felipe Aquino: Portuguese citizen of Japanese-Portuguese ancestry whom Toguri married in 1945.

Walter Winchell: Influential American broadcaster who campaigned for Toguri’s prosecution.

President Gerald Ford: U.S. President who pardoned Toguri in 1977.

Related products

-

Vietnam War: CIA Chronology of the Conflict, 1940-1973 (1974)

$1.99 Add to Cart -

Trial Notes of Ralph G. Albrecht, Prosecutor at the Nuremberg Trials of World War II

$3.94 Add to Cart -

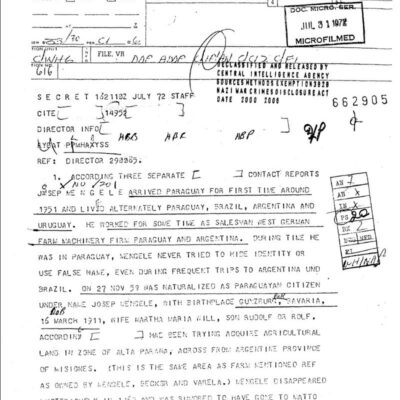

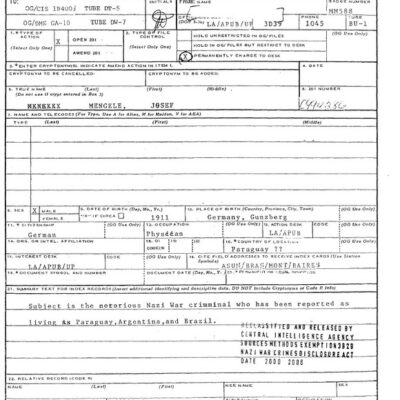

Josef Mengele CIA Files

$19.50 Add to Cart -

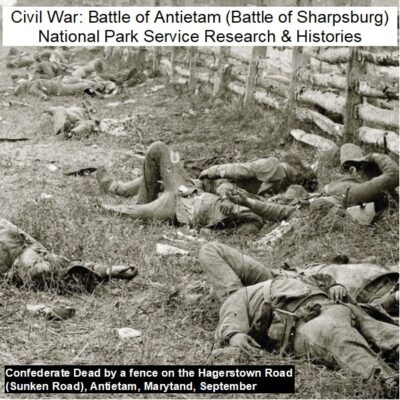

Civil War: Battle of Antietam (Sharpsburg) – National Park Service Archives

$9.99 Add to Cart