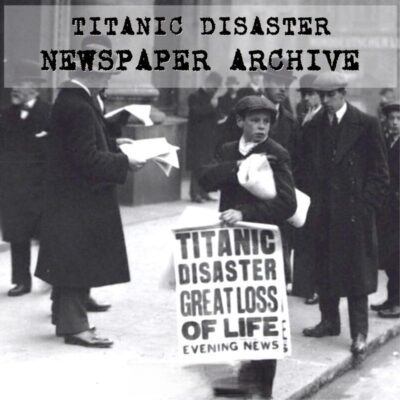

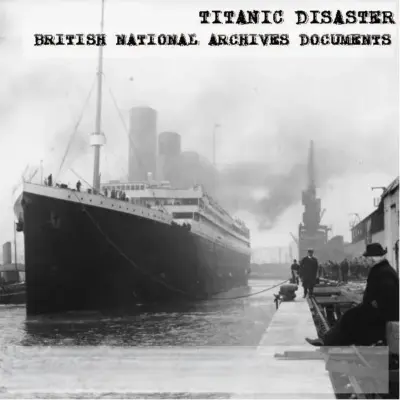

Titanic Disaster: White Star Line and Passenger Legal Documents

$19.90

Description

Titanic Disaster Court Documents from White Star Line – Download Available

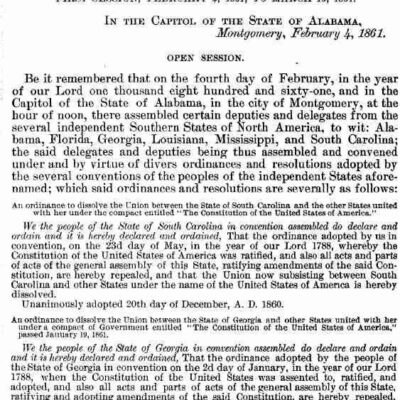

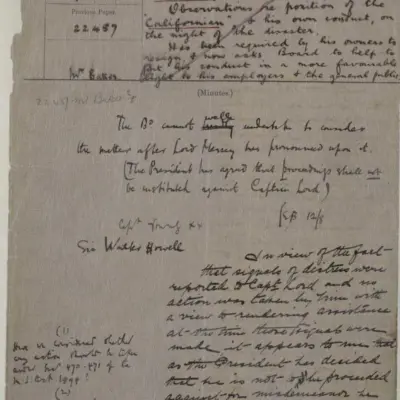

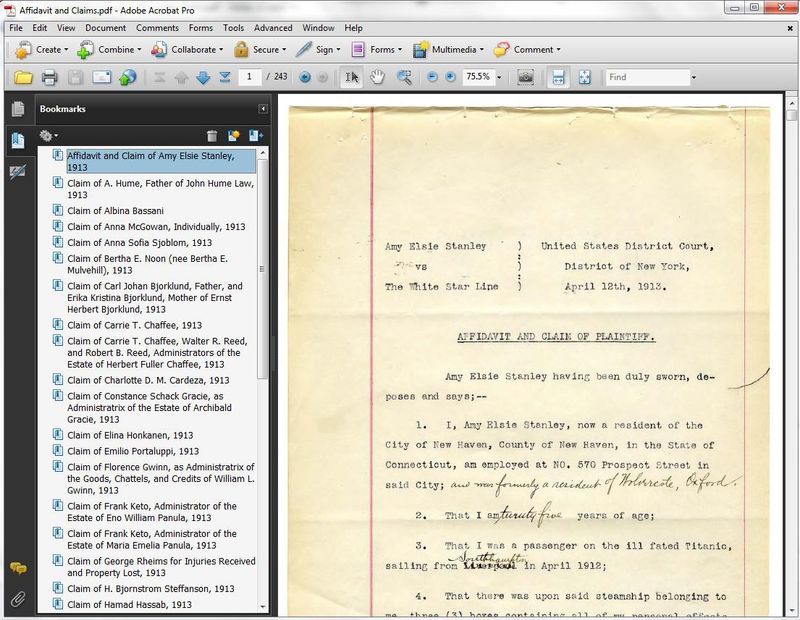

There are 1,100 pages of legal documents related to the RMS Titanic disaster, housed in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York. These documents include a petition submitted by the Oceanic Steam Navigation Company, which owned the Titanic, seeking to limit their liability, along with responses from various claimants. This material is sourced from the National Archives and Records Administration.

The legal case titled “In the Matter of the Petition of the Oceanic Steam Ship Company, Limited, for Limitation of its Liability as owner of the steamship TITANIC” was initiated under the liability laws existing at the time of the Titanic tragedy. These laws enabled the owners of the White Star Line to request that the courts restrict their financial responsibility following the incident.

This case file is rich with court documents, evidence, testimonies from surviving passengers, and claims made by survivors and representatives of those who lost their lives. Several of these records narrate personal accounts of the sinking event with gripping detail.

In their petition, the White Star Line argued that the collision was an unavoidable accident. The liability for the Titanic was subject to the 1851 “Act to Limit the Liability of Ship-Owners, and for other Purposes.” This legislation was established to foster shipbuilding and trade by reducing the potential risks faced by owners when maritime disasters occurred.

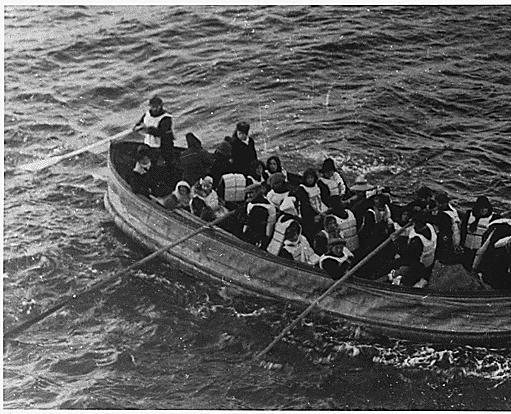

The law stipulated that maritime companies would not be held liable for any loss of life, property damage, or injuries resulting from accidents deemed unavoidable. If it could be demonstrated that mistakes made by the captain and crew led to the disaster, but the ship’s owners were unaware of those errors, the liability of the company would be confined to the total of passenger fares, the value of cargo on board, and any materials salvaged from the wreck site. The 712 people who survived the Titanic disaster, along with the families of the 1,517 individuals who lost their lives, could collectively receive a maximum compensation amounting to $91,805. This sum breaks down into $85,212 designated for passengers, $2,073 allocated for cargo losses, and an additional $4,520 for the only items recovered from the wreck, specifically the lifeboats.

In order to secure a higher compensation amount, those filing claims must demonstrate that the owners of the Titanic were aware of the conditions that led to the ship’s tragic sinking. If claimants can establish not only the negligence of the captain and crew but also show that the Titanic’s owners had prior knowledge of these negligent behaviors, legal restrictions on the company’s financial responsibility could potentially be lifted.

Following the tragic event, White Star Line submitted its petition, which was accompanied by notices published in the New York Times from October 1912 to January 1913. These notices aimed to inform individuals who believed they were entitled to compensation that they needed to submit their evidence by April 15, 1913. As a result of this outreach, the company received hundreds of claims from across the globe, culminating in a total of $16,604,731. The claims were categorized into four distinct categories: Schedule A focused on Loss of Life, Schedule B dealt with Loss of Property, Schedule C included claims related to both Loss of Life and Property, and Schedule D covered Injury and Property claims.

This collection includes numerous documents pertaining to the claims made in this case. It is important to note that survivors of the Titanic incident often faced physical injuries as well. For instance, among the claims documented was one from Anna McGowan, a resident of Chicago, Illinois, who reported that she failed to board a lifeboat before it departed and was consequently forced to leap from the Titanic into a lifeboat below. In her claim, she asserted that she endured lasting injuries from the fall, as well as experiencing shock and frostbite. Her submission indicated that the traumatic ordeal resulted in a condition described as “nervous prostration,” rendering her incapable of self-sustenance. Patrick O’Keefe, hailing from Ireland, also leaped into the tumultuous waters in a bid to save himself. However, he spent several hours adrift in a collapsible raft in the frigid Atlantic Ocean before being saved by lifeboat B.

Bertha Noon, a resident of Providence, Rhode Island, submitted a claim seeking $25,000 for the injuries she incurred after being forcibly pushed onto a lifeboat and then left exposed to the cold conditions for an extended period prior to her rescue by the Carpathia. Her detailed list of damages includes a back and spine injury that resulted in her being “unable to wear corsets,” severe psychological trauma, a “misplaced womb,” and persistent congestion in her head and chest that led to bouts of delirium and unconsciousness lasting several days.

In the context of property loss claims, there were notable items mentioned, including three crates filled with ancient models intended for the Denver Museum belonging to Margaret “Molly” Brown, documents related to the War of 1812 owned by Colonel Archibald Gracie, and over 110,000 feet of motion picture film that belonged to William Harbeck. The most valuable single item lost during the sinking was an oil painting titled La Circasienne Au Bain by Blondel, measuring four feet by eight feet, which H. Bjornstrom-Steffanson valued at $100,000.

While the Schedule A claims submitted by relatives for those lost during the tragedy did not provide direct testimonies about the incident, they highlighted profound losses. John Panula, a Finnish immigrant, was looking forward to reuniting with his family in Pennsylvania when tragedy struck, resulting in the deaths of his wife and four children aboard the Titanic. The claims made for losses after the Titanic disaster highlight significant class disparities. The requests for compensation also illustrate the different values people assigned to human life. For instance, Emily J. Innes-Meo, the widow of Alfonso Meo, claimed only £300 (which was around $1,500 back then), whereas Irene Wallach Harris, whose husband Henry B. Harris was a Broadway producer and theater owner, sought a much larger sum of $1 million. Many claimants included specific details about the deceased, such as their ages and annual incomes, in order to substantiate the amounts they were requesting.

As these individuals pursued financial recompense, they gradually constructed a case against the White Star Line. They argued that even though the crew received wireless alerts regarding iceberg locations, the Titanic continued at full speed, remained on its original northern trajectory, did not assign additional lookouts, and neglected to equip the lookouts with binoculars.

Furthermore, they criticized the White Star Line for inadequately preparing the crew for evacuation procedures, which resulted in lifeboats being launched with insufficient occupants, contributing to further loss of life. Given these factors, along with the presence of J. Bruce Ismay, the managing director of the White Star Line, aboard the Titanic, the claimants contended that the company should be held fully responsible.

In June 1915, the case reached the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York after the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the British owners of the White Star Line. The ruling determined that U.S. laws, rather than British laws, should govern the claims arising from the sinking of the Titanic. In December 1915, a resolution outside of court was achieved that resulted in a total compensation amounting to $665,000 being distributed among all individuals who had made claims. Given that this settlement took place outside of the judicial system, there is a lack of public documentation detailing how this sum was allocated among the different claimants. At that time, various newspaper reports provided differing accounts regarding the distribution of the funds.

In July 1916, a definitive ruling was issued by Judge Julius M. Mayer, which declared that the company bore no responsibility or awareness regarding the incidents in question and therefore would not be held accountable for any losses, damages, injuries, destruction, or fatalities that occurred.

Notable excerpts from the relevant documents include:

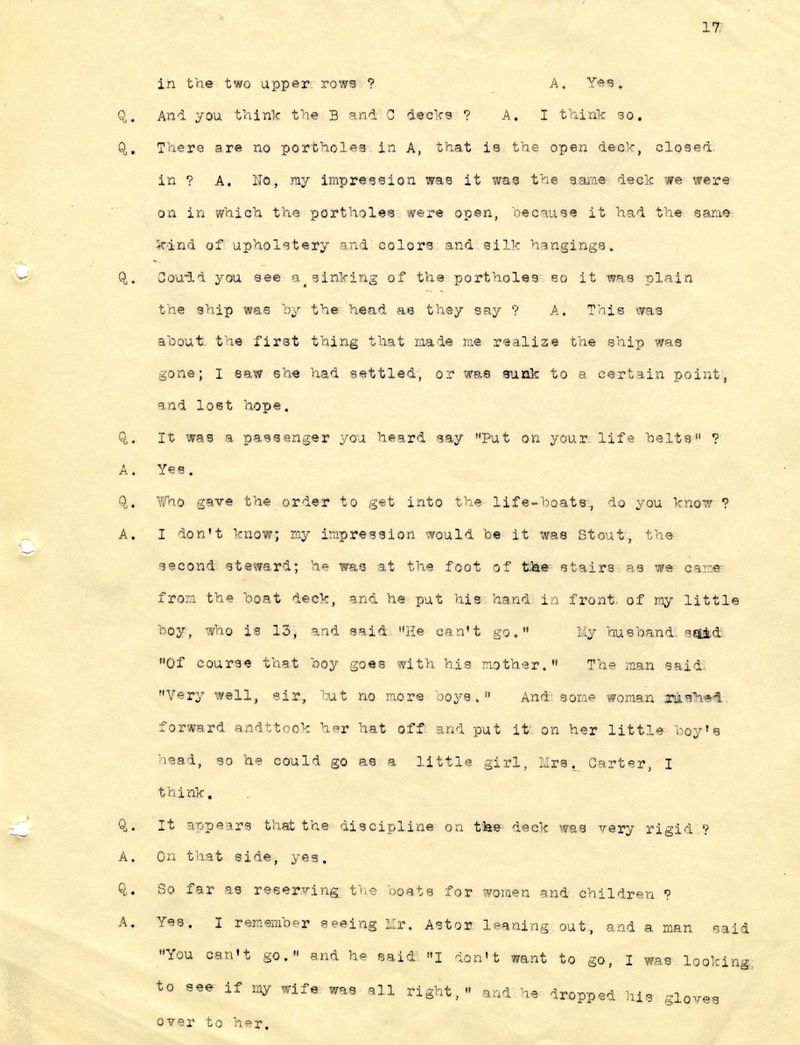

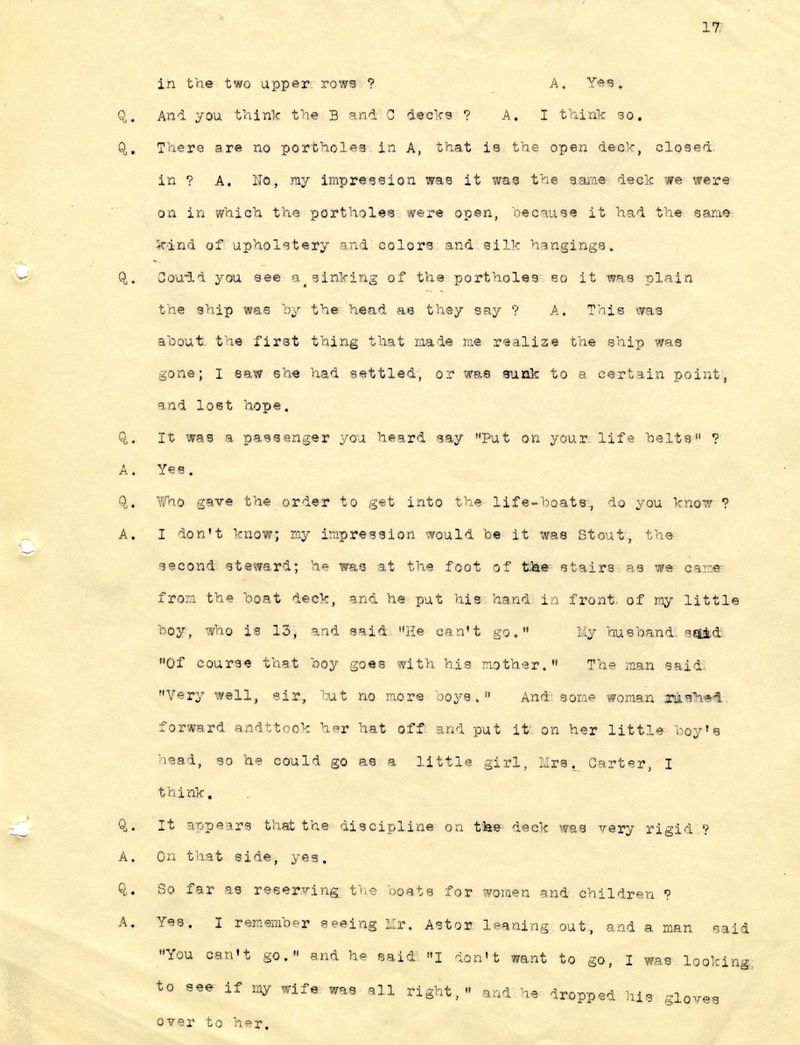

Testimony from Emily Ryerson

Emily Ryerson (August 10, 1863 – December 28, 1939) was a first-class passenger who survived the tragic sinking of the RMS Titanic. In her testimony, she recounted her experience while evacuating the ship: “…Stout, the second steward; he was positioned at the bottom of the stairs as we descended from the boat deck, and he placed his hand in front of my young son, who is 13, stating ‘He can’t go.’ My husband responded, ‘Of course that boy goes with his mother.’ The steward replied, ‘Very well, sir, but no more boys.’ At that moment, a woman hurried forward, removed her hat, and placed it on her little boy’s head so that he could pass as a girl…”

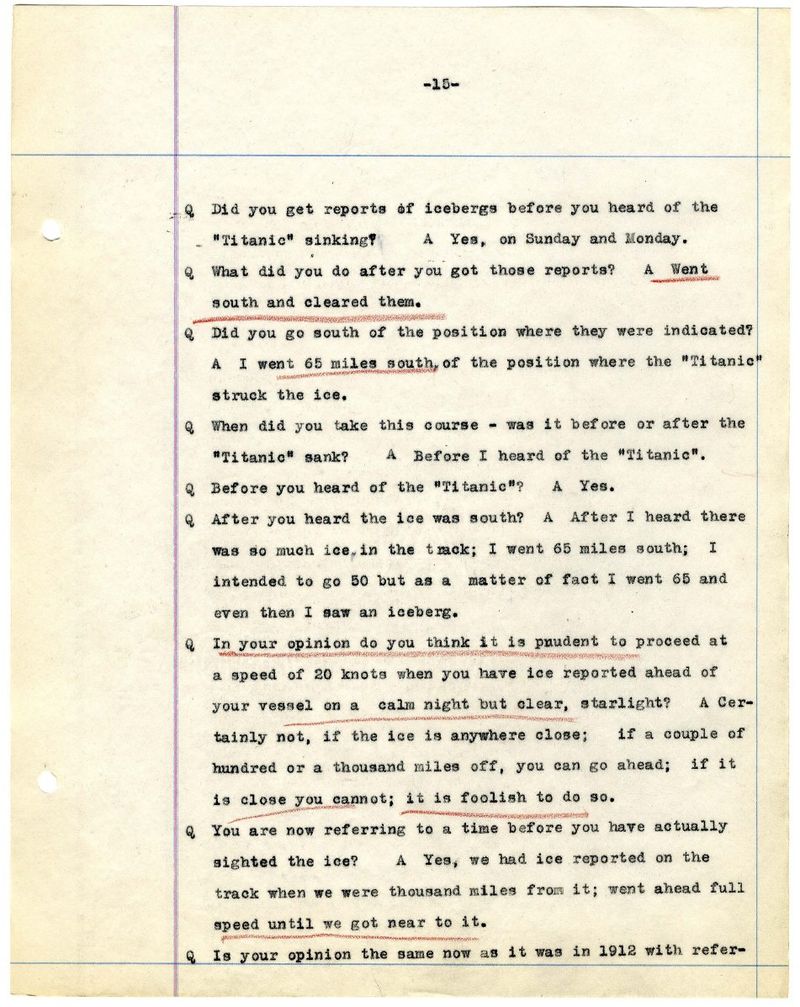

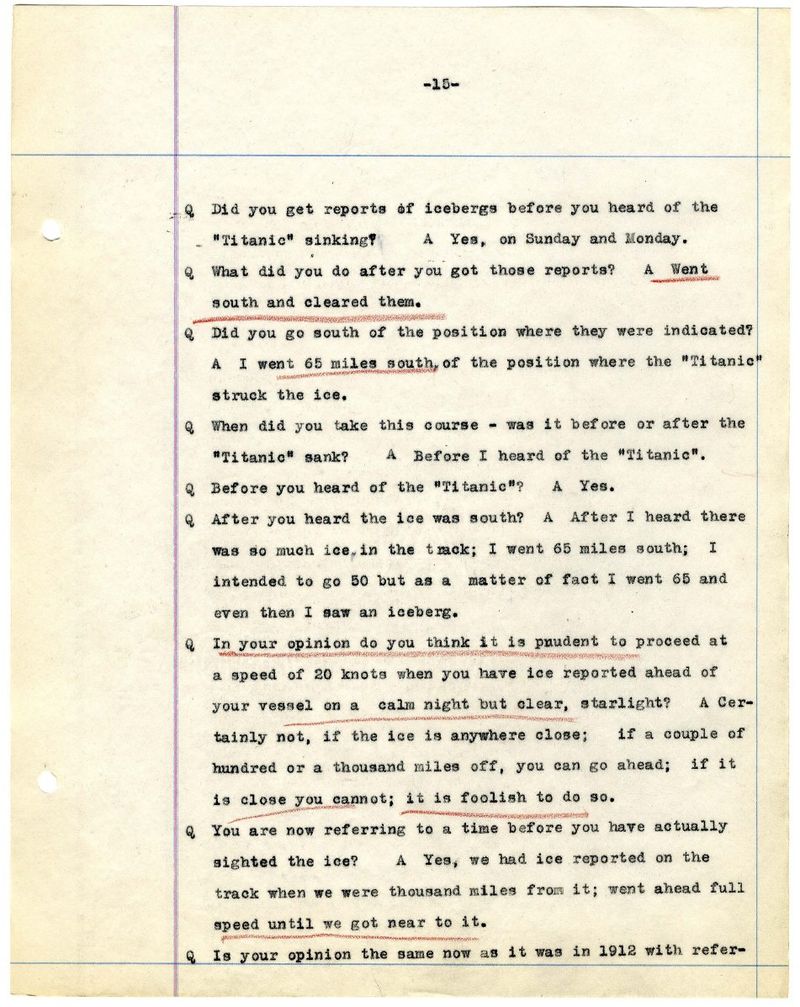

Testimony from William Thomas Turner William Turner (October 23, 1856 – June 23, 1933) held the position of captain aboard the RMS Lusitania when it met its tragic fate, being struck and sunk by a German submarine in May 1915. In a distinctly rare document, Captain Turner is interviewed regarding the Titanic disaster, a mere week prior to the Lusitania’s own demise. On the eve of the Lusitania’s last journey, April 30, 1915, Captain Turner found himself at the New York City offices of the law firm Hunt, Hill & Betts. He had been summoned to provide his testimony in relation to an ongoing legal case concerning the limitations of liability for the Titanic disaster, a case that was already extending into its third year. During this inquiry, he faced numerous questions regarding aspects such as the dimensions and construction of Cunard Line vessels, the challenges associated with detecting icebergs, and his responses to iceberg alerts. These inquiries were significant since the vessel he had captained, the RMS Mauretania, had sailed just a few days after the Titanic incident in April 1912.

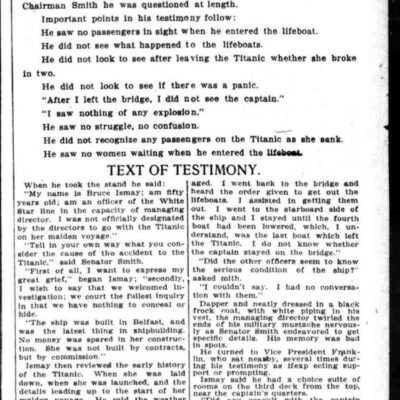

In regard to J. Bruce Ismay, who served as both chairman and managing director of the White Star Line, he became widely known as the highest-ranking official from the company among the 712 individuals who survived the tragic sinking. In June 1914, Ismay faced scrutiny about various factors related to the Titanic, including its operational speed, the adequacy of its lifeboat provisions, the presence and effectiveness of lookouts, and other elements that may have played a role in the tragedy. Throughout his testimony, Ismay reiterated many of the same points he had made during congressional hearings in April 1912 following the disaster, stressing that all critical decisions were made solely by Captain Edward Smith. He also maintained that his presence aboard the ship was primarily to evaluate potential improvements for passenger accommodations on the White Star Line’s next vessel, the Britannic.

When discussing Margaret “Molly” Brown, famously dubbed “The Unsinkable Molly Brown,” her claims and reputation stand out in the narrative of maritime disasters. The Unsinkable Molly Brown submitted a claim for her lost possessions, which comprised a significant assortment of dresses, hats, jewelry, and even ancient Egyptian artifacts designated for the Denver Museum. Her inventory of missing items included: one sealskin jacket valued at $700; a necklace priced at $20,000; fourteen hats costing $225; three dozen gloves worth $50; along with two Japanese kimonos. The grand total of her claim amounted to $27,887.

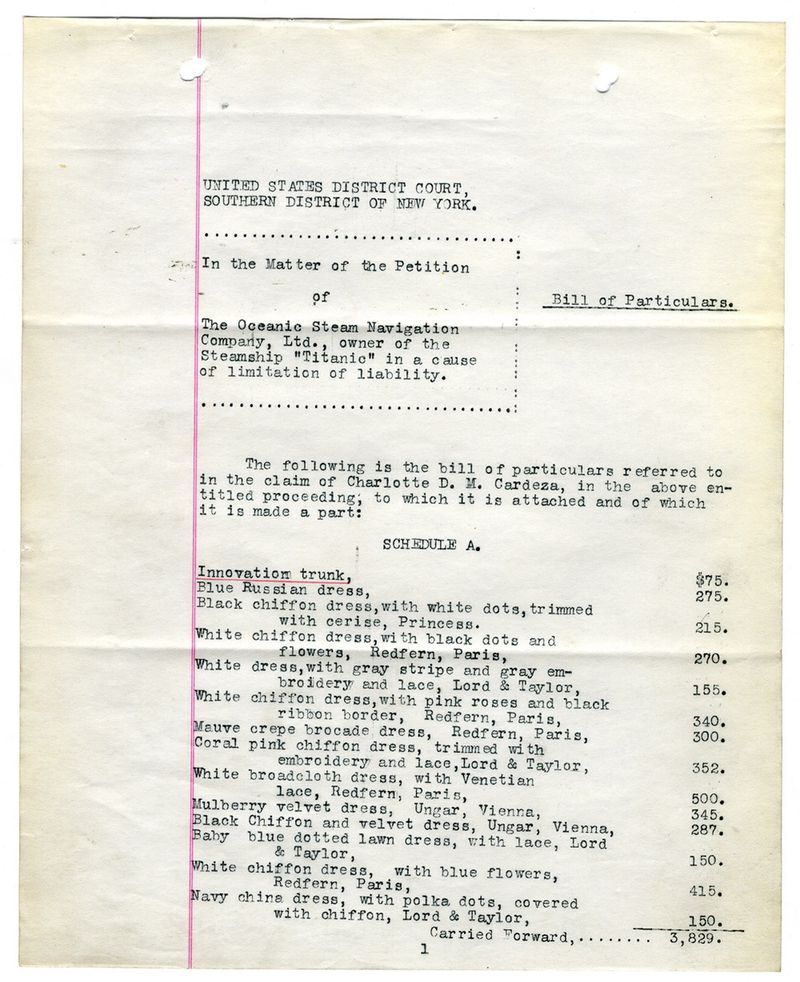

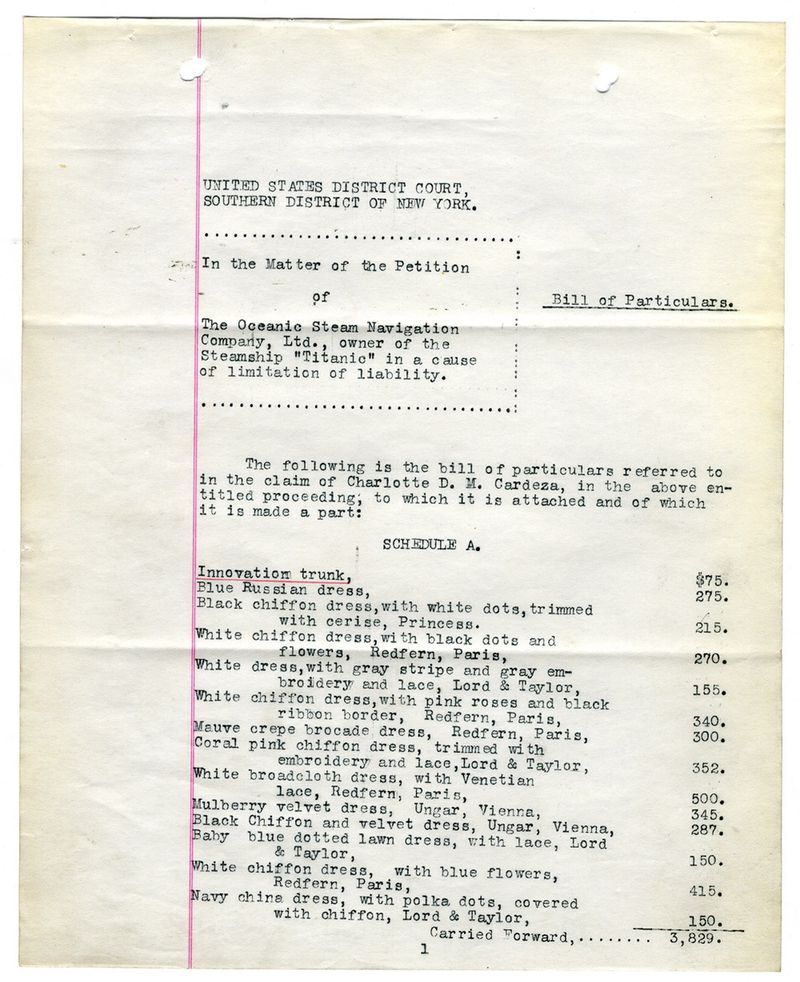

Charlotte Drake Cardeza’s Claim

Charlotte Drake Cardeza, a well-known socialite, was not one to travel with minimal baggage. Her claim stands out as it is the longest in this collection. She occupied the priciest stateroom on the Titanic and managed to survive the disaster by boarding lifeboat 3. Cardeza sought compensation for the lost contents from her fourteen trunks, four suitcases, and three crates of luggage, totaling no less than 841 individual items, amounting to $177,352.75. Among the listed items was a stunning 6 7/8-carat pink diamond ring appraised at $20,000.

Testimony from Elizabeth Lines

During her statement, passenger Elizabeth Lines describes overhearing Bruce Ismay commenting to Captain Smith about the swift progress of the ship’s journey, claiming they would outpace the Olympic and arrive in New York by Tuesday.

Affidavit of Value

This legal document submitted by the Oceanic Steam Navigation Company estimates the total value of passenger losses at $91,805.54

Timeline of Events: Titanic Legal Aftermath: 1912-1916

This timeline is constructed from the limited information provided in the source about the sinking of the Titanic and the subsequent legal proceedings.

April 1912:

- April 10: The RMS Titanic departs Southampton, England.

- April 14: The Titanic strikes an iceberg in the North Atlantic and sinks. Over 1,500 people perish.

October 1912 – January 1913:

- The Oceanic Steam Navigation Company, owners of the White Star Line, publishes notices in the New York Times informing individuals with claims for damages to file proof by April 15, 1913.

April 1913:

- Deadline for submission of claims for damages resulting from the sinking of the Titanic.

June 1914:

- J. Bruce Ismay, Managing Director of the White Star Line, is questioned in court regarding his role and decisions made onboard the Titanic.

June 1915:

- The case regarding the limitation of liability for the Titanic disaster reaches the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York after the Supreme Court ruled in favor of applying US law to the claims.

December 1915:

- An out-of-court settlement of $665,000 is reached for all claimants. The specifics of the distribution remain undisclosed.

July 1916:

- Judge Julius M. Mayer signs a final decree absolving the White Star Line of any direct knowledge or responsibility for the losses, damages, injuries, and fatalities resulting from the sinking.

Cast of Characters

Key Figures in the Titanic Disaster and Legal Proceedings:

- J. Bruce Ismay: Chairman and Managing Director of the White Star Line. A survivor of the sinking, Ismay faced intense scrutiny and public criticism for his actions during the disaster, particularly for boarding a lifeboat while passengers remained on board.

- Captain Edward Smith: Captain of the RMS Titanic. Smith perished with the ship.

- William Thomas Turner: Captain of the RMS Lusitania. Turner testified in the Titanic liability case, providing insight into maritime practices and safety standards of the time.

- Emily Ryerson: A first-class passenger who survived the sinking. Ryerson’s deposition provides a firsthand account of the chaotic evacuation process.

- Patrick O’Keefe: A survivor who jumped overboard from the sinking ship and endured hours in the frigid Atlantic waters before being rescued.

- Bertha Noon: A survivor who suffered injuries during the evacuation and filed a claim for damages resulting from physical and emotional trauma.

- Margaret “Molly” Brown: A well-known socialite and philanthropist who survived the sinking. Brown is remembered for her bravery in assisting other passengers and her efforts to manage Lifeboat No. 6. She filed a claim for lost property, including a valuable collection of belongings.

- Charlotte Drake Cardeza: A wealthy socialite who survived the sinking. Cardeza filed one of the largest claims for lost property, detailing an extensive collection of luxury items.

- John Panula: A Finnish immigrant whose wife and four children tragically perished in the sinking.

- Emily J. Innes-Meo: Widow of Alfonso Meo, who filed a claim for the loss of her husband.

- Irene Wallach Harris: Widow of Broadway producer Henry B. Harris, who filed a substantial claim for the loss of her husband.

- Elizabeth Lines: A passenger who testified to overhearing a conversation between Ismay and Captain Smith regarding the speed of the ship.

- Judge Julius M. Mayer: The presiding judge in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York who ultimately signed the final decree in the liability case.

Note: This information is based solely on the provided source. Further research can provide a more comprehensive understanding of the events and individuals involved.