Titanic Disaster: Newspaper Articles (1912-1922)

$19.90

Description

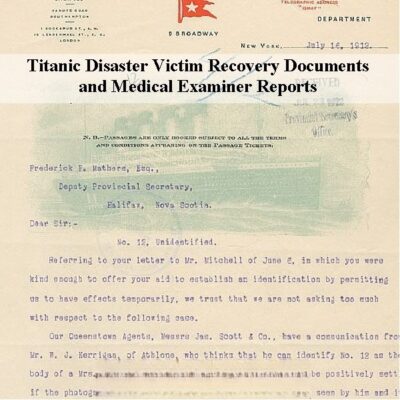

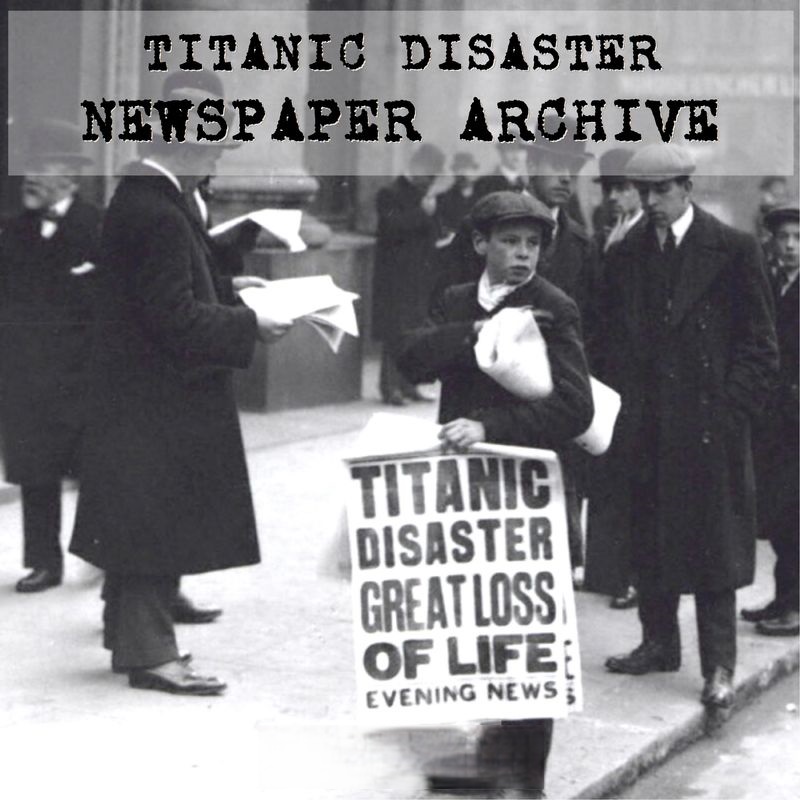

TITANIC DISASTER NEWSPAPER ARCHIVE

This archive contains a carefully curated selection of 1,200 complete pages from American newspapers, spanning from April 1, 1912, to April 14, 1922. These pages document not only the tragic sinking of the Titanic but also the subsequent impact and fallout that ensued. The majority of these newspaper articles were published during the first six months following the disaster.

TITANIC DISASTER NEWSPAPER ARCHIVE

April 14 is marked by two significant historical incidents that vie for attention. At exactly 10:00 p.m. on April 14, 1865, the infamous actor John Wilkes Booth made his way into the presidential box at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C., where he assassinated President Abraham Lincoln. Fast forward 47 years to approximately 11:40 PM on April 14, 1912, when the R.M.S. Titanic, on her maiden voyage, collided with an iceberg near the coast of Newfoundland and ultimately sank by around 2:20 a.m. the following morning, resulting in the tragic loss of 1,517 lives.

The tragedy of the Titanic marked the advent of international news coverage in the twentieth century, making it one of the first events to receive immediate and extensive reporting on a global scale. By the year 1912, advancements in telegraphy and photography had progressed to such an extent that information regarding the catastrophe could be disseminated rapidly and broadly.

American newspapers experienced a distinct advantage over their British counterparts due to the fact that many survivors were brought to New York City. This proximity allowed American publications to place some of their most skilled reporters on the scene when the U.S. Senate held its first inquiry into the disaster at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in New York City, just a day after the survivors arrived.

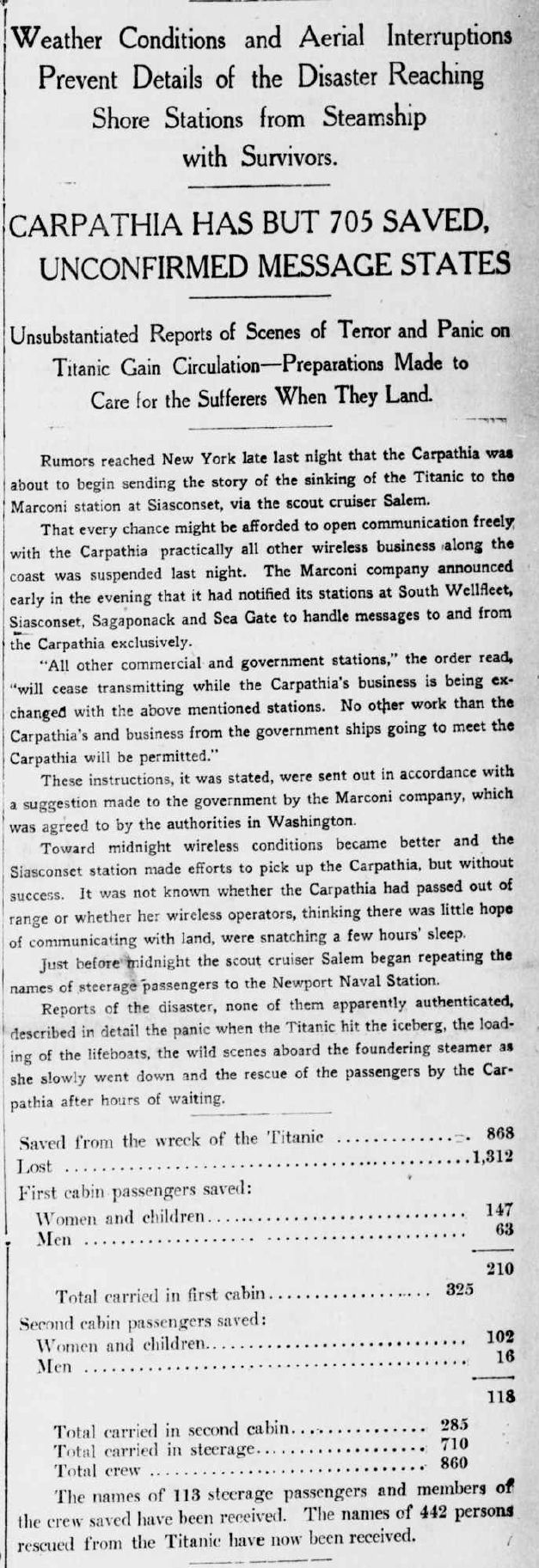

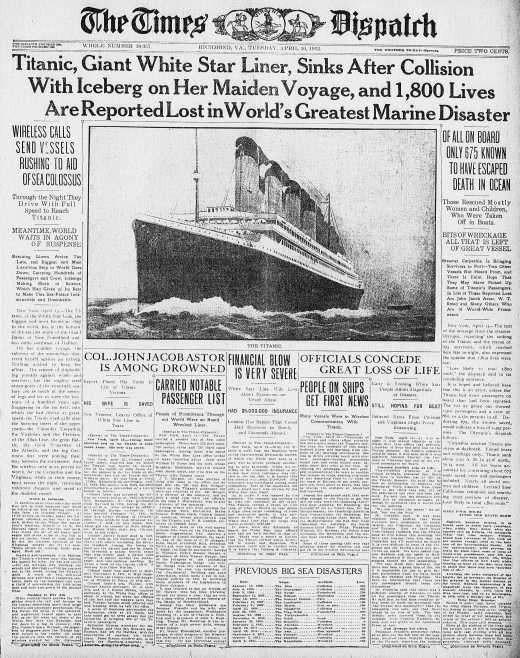

A notable example of the confusion surrounding the event can be seen in the London Daily Mail, which unfortunately published a misleading headline on April 16, 1912, stating, “Titanic Sunk. No Lives Lost. Collision with an Iceberg. Largest Ship in the World. 2,358 Lives in Peril. Rush of Liners to the Rescue. All Passengers Taken Off.” In stark contrast, the New York Herald reported the incident the next day with a more accurate headline: “The Titanic Sinks with 1,800 on Board; Only 675, Mostly Women and Children, Saved.” The initial coverage of the Titanic’s maiden voyage was surprisingly minimal, with little excitement generated in the press.

Newspapers that would later create some of the most sensational headlines of the early 1900s were quite brief in their reports when the ship first embarked on its journey. For instance, the New York Tribune, which would go on to publish one of the most notorious headlines about the Titanic disaster just days later, only included a short two-sentence article on page six of its fourteen-page edition on April 11, 1912. This article simply stated that “The White Star liner Titanic, which sailed from Southampton yesterday, is now ‘the largest vessel of the world.’ But how long will it be before there is a super-Titanic?” In contrast, ten months prior, newspapers had extensively reported on the inaugural voyage of Titanic’s sister ship, The RMS Olympic, which took place on June 14, 1911, making the Titanic’s first journey seem like old news before it even began.

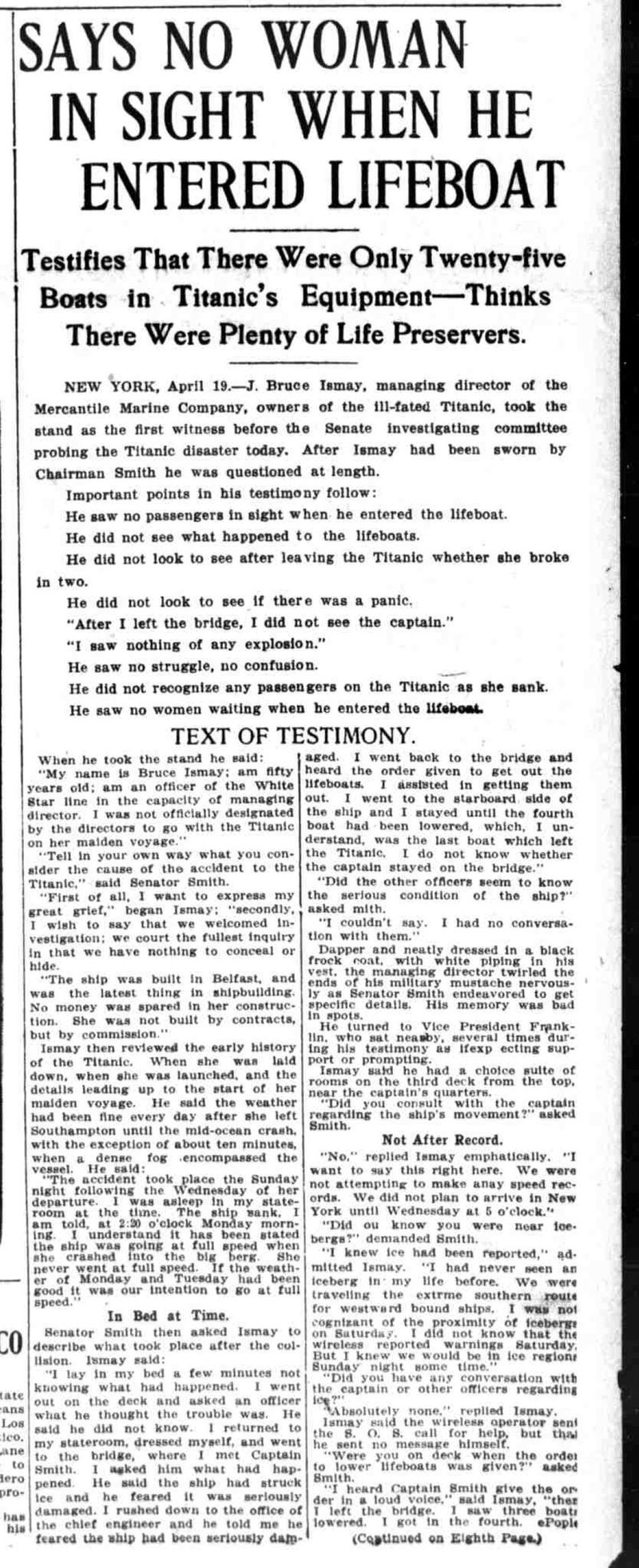

The initial reports regarding the Titanic disaster, published on April 15, contained numerous errors and inaccuracies. An optimistic bias was evident in the earliest headlines and articles concerning the fate of the luxurious ship and its passengers. However, the stark reality of the tragedy became apparent as more accurate information began to circulate after April 16. From April 17 onward, many newspapers started to provide more comprehensive accounts of the sinking, reflecting a clearer and more precise understanding of the situation. One significant reason for the extensive media coverage of the Titanic disaster was the presence of many affluent and prominent individuals on board. Among them were Mr. and Mrs. John Jacob Astor, a wealthy couple; Benjamin Guggenheim, a rich businessman; Major Archibald Willingham Butt, who served as military aide to President Taft; J. Bruce Ismay, the managing director of the White Star Line; William T. Stead, a well-known English journalist; Isidor Strauss, an affluent New York merchant and co-owner of Macy’s; Denver millionaire Margaret “Molly” Brown; Frank Millet, a respected artist; James Clinch Smith, a sportsman and member of high society in both New York and Paris; and Henry B. Harris, a theatrical producer and manager.

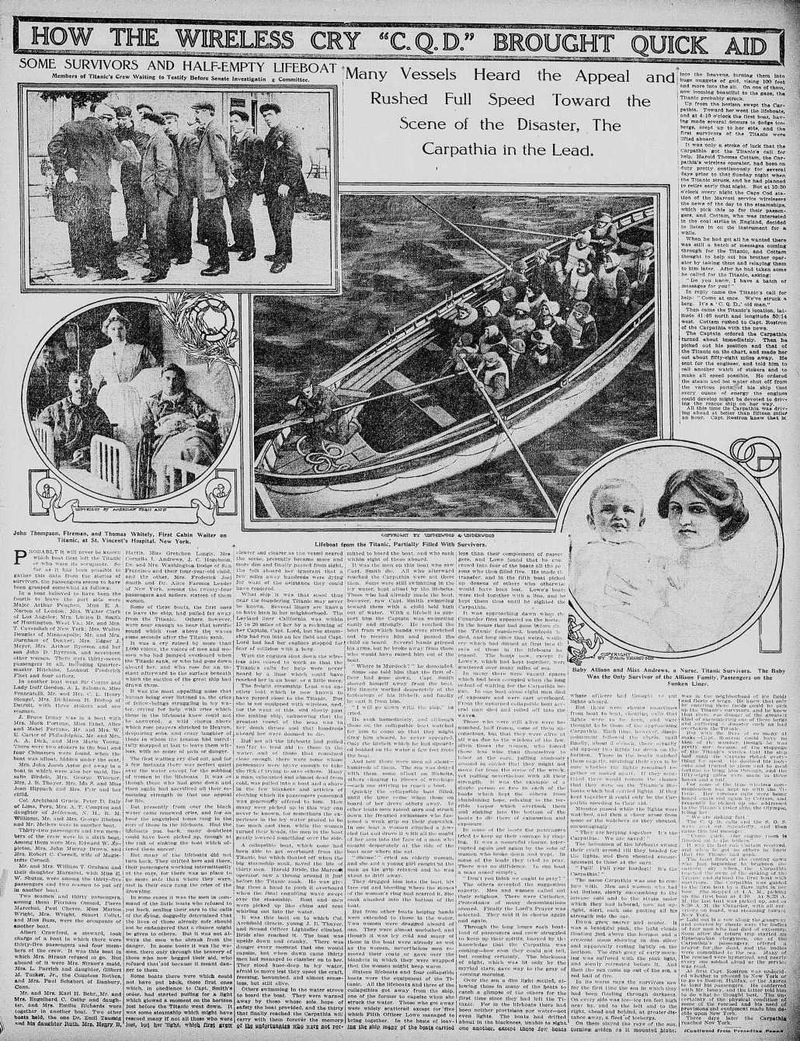

The media stoked public fascination with the Titanic tragedy by providing sensational headlines, detailed reports, personal stories, dedicated sections, images, and opinion pieces. This body of work illustrates the struggle between the necessity of selling newspapers and the commitment to delivering accurate news.

The tragedy and sorrow that accompanied the sinking of the Titanic sparked a deep human desire to discover elements of heroism or redemption within the calamity. However, subsequent scholarly investigations have failed to corroborate many of the exaggerated narratives of bravery and self-sacrifice that captured the attention of a shocked audience. For instance, most researchers studying the Titanic cannot find substantial evidence to back up the popular account claiming that Major Butt bravely intervened to prevent men from abandoning women and children during the evacuation of the sinking ship.

An article from the April 19, 1912 edition of the Los Angeles Times proclaimed: “Maj. Butt with Gun in Hand, Held Back Frenzied Men, Saved Women; Capt. Smith a Suicide on Bridge.” In later reports, other newspapers elaborated on this story, suggesting that it was “crazed Sicilian men” who required being threatened at gunpoint to facilitate the escape of women and children from the Titanic in lifeboats. The newspaper articles provide insights into various aspects of the Titanic disaster that continue to generate debate even today. A notable point of contention is the music played by the ship’s band as it went down; some witnesses claim they were playing the hymn “Autumn,” while others insist it was “Nearer My God to Thee.” There are also discrepancies regarding the final moments of Captain Smith, with different accounts circulating in the media. Over the past century, certain narratives have become widely accepted, such as the story of Mrs. Strauss, who reportedly chose to forfeit her seat in a lifeboat to stay with her husband, and the claims of Bruce Ismay’s alleged cowardice when he boarded a lifeboat despite women and children still waiting for their turn.

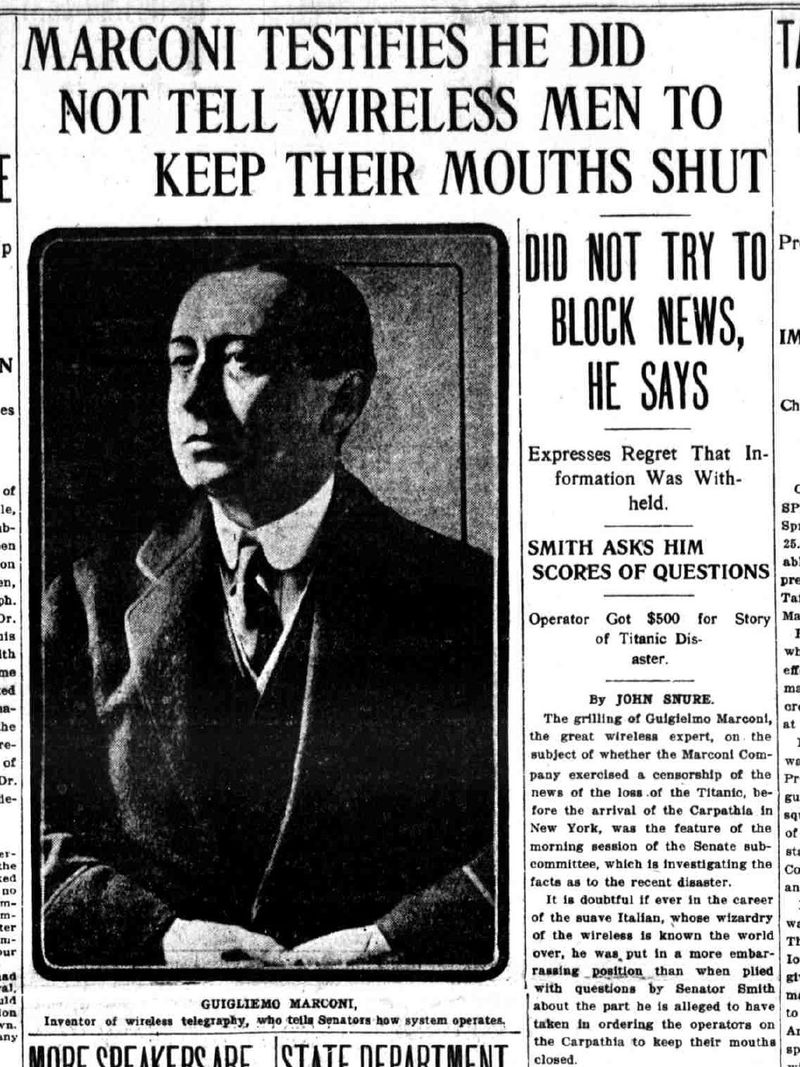

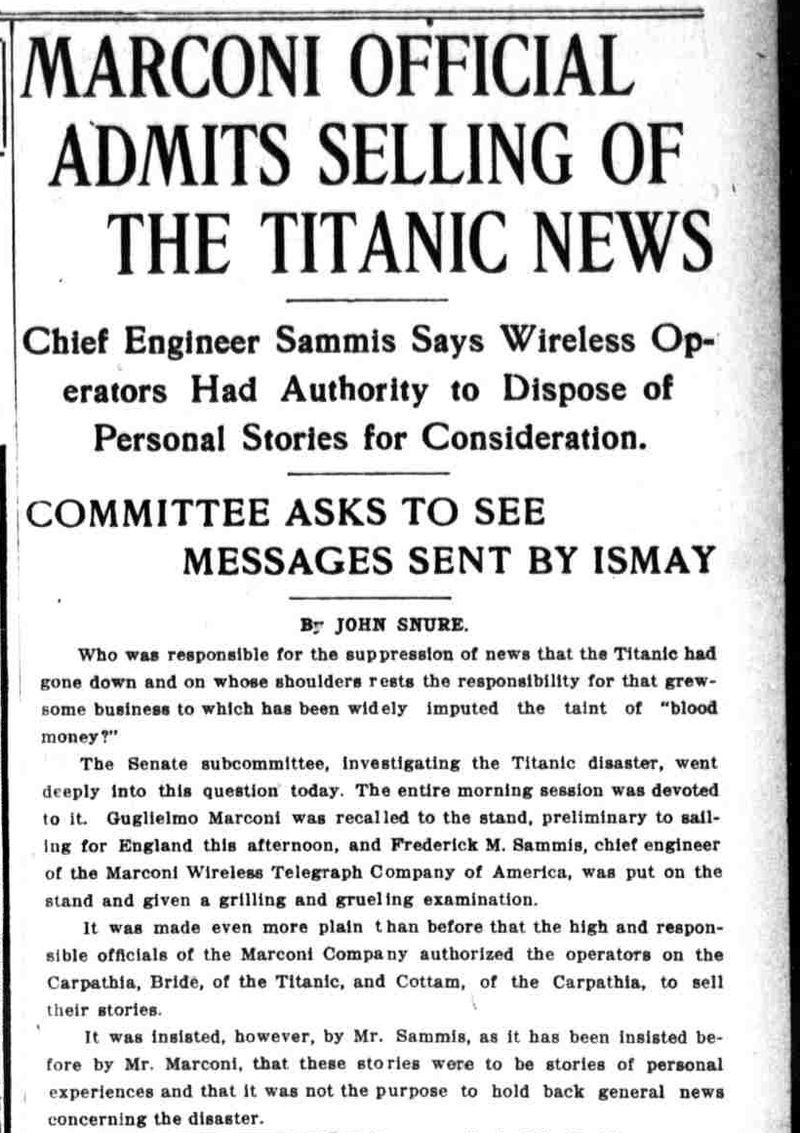

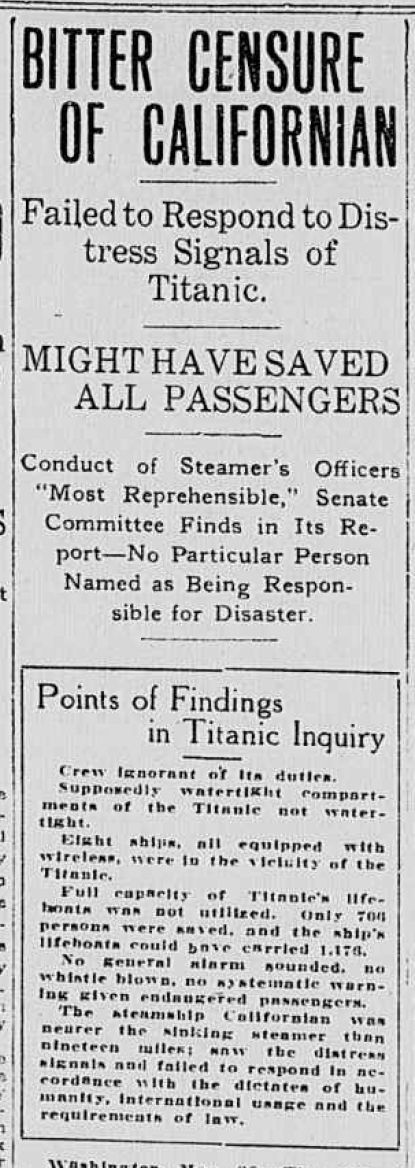

The newspapers covered a wide array of topics related to the Titanic incident. Among these were reports of iceberg sightings near the location where the ship sank, the rescue efforts made by the Carpathia to save survivors and bring them back to shore, and the American inquiry into the tragedy conducted by the United States Senate, led by Senator William A. Smith, which saw eighty-two witnesses testify. Additionally, there were firsthand accounts from Titanic survivors detailing their experiences during the sinking, as well as various theories about what caused the disaster, some of which seem quite absurd by today’s standards. Reports also examined the involvement—or lack thereof—of other vessels like the Carpathia, SS Californian, Mackay-Bennett, Minia, Montmagny, and the Algerine in relation to the event.

Other topics included the attempts to recover the bodies of Titanic victims from the ocean, the British Board of Trade’s inquiry into the calamity, and evaluations regarding the reasons behind the Titanic sinking, along with suggestions aimed at preventing future maritime disasters. While the Titanic serves as the central theme of this collection, its tragic sinking coincided with several other significant news stories from that time.

Among these noteworthy events that were reported alongside the Titanic tragedy are: The fierce and contentious competition for the Republican presidential nomination in 1912, which was characterized by a rivalry between Incumbent President William Howard Taft and former president Theodore Roosevelt; Following his unsuccessful bid for the Republican nomination, Theodore Roosevelt established the Progressive Party, often referred to as the “Bull Moose Party”; The commencement of the Summer Olympic Games in Stockholm, Sweden; The ongoing turmoil of the Mexican Revolution featuring the prominent figure Pancho Villa; The landing of U.S. Marines in Cuba; The emerging movement advocating for the prohibition of alcohol; The increasing influence of labor unions and the occurrence of various labor strikes; The passing of aviation pioneer Wilbur Wright; The United States’ military occupation of Nicaragua; The onset of the First Balkan War involving Bulgaria, Greece, Montenegro, Serbia, and Turkey; Additionally, fashion trends of the period were showcased through advertisements published by retailers like Gimbels, Lord & Taylor, and Macy’s.

The newspapers included in this compilation feature:

- New York Times

- Los Angeles Times

- Washington Times

- New York Tribune

- The Washington Herald

- The Sun (New York City, NY)

- The Evening World (New York City, NY)

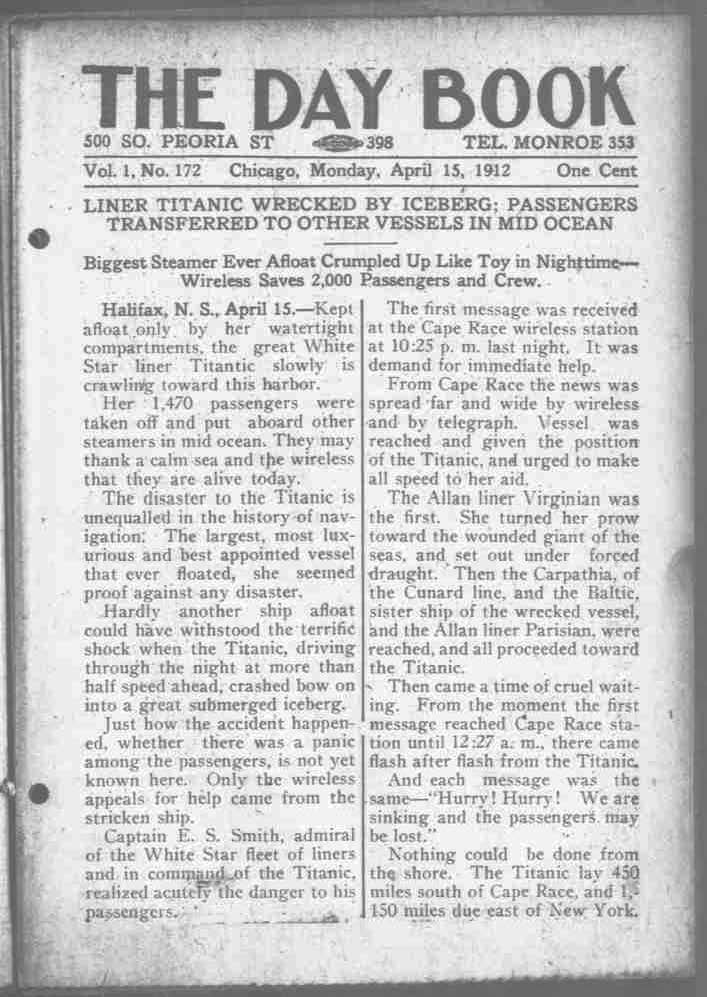

- The Day Book (Chicago, IL)

- Trenton Evening Times

- The Times Dispatch (Richmond, VA)

- The San Francisco Call

- El Paso Herald

- Medford Mail Tribune (Medford, OR)

- The Watchman and Southron (Sumter, SC)

- The Tacoma Times

- New Brunswick Times (New Brunswick, NJ)

- The Evening Standard (Ogden City, UT)

- Evening Bulletin (Honolulu, HI)

- The Hawaiian Star (Honolulu, HI)

- The Hawaiian Gazette (Honolulu, HI)

- The Yakima Herald (Yakima, WA)

- Weekly Journal-Miner (Prescott, AZ)

- The Democratic Banner (Mt. Vernon, OH)

- The Citizen (Honedale, PA)

- Bisbee Daily Review (Brisbee, AZ)

- Burlington Weekly Free Press (Burlington, VT)

- Hopkinsville Kentuckian

- The Logan Republican (Logan, UT)

- The Mathews Journal (Mathews Court House, VA) The photographs presented consist of scanned newspaper articles that can be found in several prominent institutions, including the Library of Congress, the National Archives and Records Administration, The New York Public Library, the California State Library, and the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Library. Additionally, these scans are also part of the collections at the Library of Virginia, the Ohio Historical Society, the Washington State Library, and the Arizona State Library Archives and Public Records. Furthermore, they are available at the University of California, Riverside, the University of Hawaii at Manoa, the University of Kentucky, the University of North Texas, as well as the Marriott Library at the University of Utah.

The quality of the collection is superior to the lower-resolution examples shown below. Users have the ability to zoom in and out on these images, which allows for both an examination of intricate details and a clearer reading of the text within the articles.

Titanic Disaster FAQ

1. How did the sinking of the Titanic become the first international news story of the 20th century to receive instantaneous, intensive coverage worldwide?

By 1912, the development and use of telegraphs and photographs had advanced significantly. This allowed news of the Titanic tragedy to be transmitted quickly and disseminated widely across the globe.

2. What were the initial reactions and reporting like in the immediate aftermath of the sinking?

Early reports, published on April 15, 1912, contained many inaccuracies and were fueled by optimism, downplaying the severity of the disaster. However, the stark reality became evident in the reporting that emerged on April 16, 1912, onward, as more accurate information became available.

3. Why did the American newspapers have an advantage over the British press in reporting on the Titanic disaster?

Survivors of the Titanic were brought to New York City, giving American newspapers direct access to firsthand accounts. They also had their best reporters present at the first inquiry into the disaster, held by the U.S. Senate in New York.

4. How did the presence of wealthy and notable individuals aboard the Titanic influence the news coverage?

The presence of prominent figures like John Jacob Astor, Benjamin Guggenheim, and Isidor Strauss heightened public interest in the disaster. Newspapers capitalized on this by publishing sensational headlines, stories, and special sections, often focusing on the experiences of these individuals.

5. Did the newspapers accurately portray the events of the sinking?

While newspapers strived to report the news, they also aimed to sell copies. This led to the publication of sensationalized and sometimes unsubstantiated stories. For instance, the heroic actions attributed to Major Archibald Butt in saving women and children have been disputed by researchers.

6. What are some of the enduring controversies and mysteries surrounding the Titanic sinking?

Debates persist regarding the final song played by the Titanic band, with some claiming it was “Autumn” and others “Nearer My God to Thee.” The last moments of Captain Smith are also shrouded in uncertainty. Additionally, the actions of Bruce Ismay, who survived the sinking, have been questioned, with allegations of cowardice.

7. What other significant events were happening in the world during the time of the Titanic disaster?

The sinking of the Titanic coincided with several notable events, including the heated 1912 US presidential election, the Mexican Revolution, the Summer Olympics in Stockholm, and growing social movements like the prohibition of alcohol and the rise of labor unions.

8. What types of newspapers are included in the “Titanic Disaster Newspaper Articles 1912-1922” collection?

The collection comprises newspapers from various regions of the United States, including major publications like the New York Times, Los Angeles Times, and Washington Times, alongside regional and local newspapers from different states and territories.