Description

The Crisis Magazine: NAACP Advocacy, 1910-1923

Detailed Timeline of Events Covered in “The Crisis” (1910-1923)

- November 1910: The first issue of The Crisis, the official magazine of the NAACP, is published. W.E.B. Du Bois pens his first editorial, outlining the magazine’s mission to expose racial prejudice and advocate for the rights of all people, irrespective of race.

- December 1910: The Crisis reports on the NAACP’s involvement in its first major legal case, the defense of Pink Franklin, a Black sharecropper in South Carolina arrested under an invalid state law after a confrontation with armed policemen resulted in the death of an officer.

- October 1913: The Crisis publishes an open letter of protest from the NAACP to President Woodrow Wilson. This follows Wilson’s mandate in 1913 to racially segregate federal government agencies, a move that reversed previous policies and led to the demotion or dismissal of some Black employees. The NAACP, through Oswald Garrison Villard, had privately urged Wilson to establish a National Race Commission to counter these discriminatory policies, but was unsuccessful.

- June 1915: The Crisis highlights the NAACP’s alarm and campaign against the release of D.W. Griffith’s film “The Birth of a Nation.” The magazine covers the NAACP’s efforts to expose the film’s racist portrayal of African Americans and its glorification of the Ku Klux Klan. The NAACP attempted to censor or ban the film through appeals to censorship boards and government officials, and organized pickets of theaters showing the movie.

- June 1918: The Crisis mentions the introduction of the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill in the House of Representatives by Congressman Leonidas C. Dyer. The bill, based on an earlier draft by NAACP founder Albert E. Pillsbury, aimed to prosecute lynchers in federal court and hold state officials accountable for failing to protect victims.

- March 1919: The Crisis reports on the resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan (the Second KKK) following the release of “The Birth of a Nation,” which romanticized the first Klan.

- Summer and Fall 1919 (“Red Summer”): The Crisis covers the widespread racial violence and race riots that erupted across the United States during the “Red Summer.” NAACP field secretary James Weldon Johnson investigates and reports on the five-day riot in Washington, D.C., triggered by sensationalized newspaper reports and attacks by white servicemen on Black pedestrians. Race riots also occurred in twenty-five other cities, including Chicago, Omaha, and Longview, Texas.

- March 1922: The Crisis publishes an article on Mahatma Gandhi, covering his philosophy and practices of non-cooperation and non-violent resistance as the leader of the Indian National Congress.

- January 1923: The Crisis features a fierce editorial by W.E.B. Du Bois following the defeat of the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill in the Senate due to a Southern Democrat filibuster. The bill had passed the House of Representatives in January 1922 after a prolonged fight. Du Bois refutes the idea that the defeat was a loss for Black people, emphasizing their moral strength in the face of violence and condemning the failure of American democracy to protect its citizens.

- Throughout 1910-1923: The Crisis serves as a platform for Black writers and artists, particularly during its “greatest era as a literary journal” between 1919 and 1926 under the literary editorship of Jessie Redmon Fauset. It publishes works by prominent figures of the Harlem Renaissance, including Arna Bontemps, Langston Hughes, Countee Cullen, and Jean Toomer. The magazine also documents the “New Negro Movement,” a period of increased racial pride, economic independence, and political activism among African Americans, fueled by the Great Migration and the experiences of Black soldiers in World War I.

Cast of Characters with Brief Bios:

- W.E.B. Du Bois (1868-1963): A prominent scholar, editor, and African-American activist. A founding member of the NAACP and the editor of The Crisis magazine for nearly 25 years. Known for his intellectual contributions, advocacy for racial equality, and opposition to Booker T. Washington’s accommodationist policies.

- Booker T. Washington (1856-1915): A leading African-American educator, orator, and advisor to multiple presidents of the United States. Advocated for a strategy of gradual progress for Black Americans through vocational training and economic self-reliance, a policy often referred to as accommodation.

- Pink Franklin: A Black South Carolina sharecropper whose arrest and murder conviction in 1910 became the NAACP’s first major legal case. His death sentence was eventually commuted, and he was later freed.

- Martin F. Ansel (1850-1945): The Governor of South Carolina who commuted Pink Franklin’s death sentence to life in prison in response to the NAACP’s appeal.

- Woodrow Wilson (1856-1924): The 28th President of the United States. Despite receiving significant African-American votes in 1912, his administration mandated racial segregation within federal government agencies in 1913.

- Oswald Garrison Villard (1872-1949): A journalist for The Nation and the treasurer of the NAACP. He met with President Wilson to protest the segregation policies and later played a role in the public release of the NAACP’s letter of protest.

- D. W. Griffith (1875-1948): An influential American film director known for his controversial 1915 film “The Birth of a Nation,” which glorified the Ku Klux Klan and presented racist stereotypes of African Americans.

- Leonidas C. Dyer (1871-1957): A Republican Congressman from Missouri who introduced the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill in the House of Representatives in April 1918.

- Albert E. Pillsbury (1842-1930): A founder of the NAACP who drafted the anti-lynching bill that served as the basis for the Dyer Bill.

- James Weldon Johnson (1871-1938): A key figure in the NAACP, serving as a field secretary. He coined the term “Red Summer” to describe the widespread racial violence of 1919 and investigated the race riots in Washington, D.C.

- Jessie Redmon Fauset (1882-1961): The literary editor of The Crisis during its most influential period as a literary journal (1919-1926). She played a crucial role in recognizing and publishing the works of many young writers associated with the Harlem Renaissance.

- Arna Bontemps (1902-1973): An African-American poet, novelist, and librarian whose work was published in The Crisis during the Harlem Renaissance.

- Langston Hughes (1901-1967): A central figure of the Harlem Renaissance, known for his poetry, plays, novels, short stories, and essays, many of which appeared in The Crisis.

- Countee Cullen (1903-1946): A prominent African-American poet associated with the Harlem Renaissance whose work was featured in The Crisis.

- Jean Toomer (1894-1967): An American poet and novelist whose experimental work, including “Cane,” was published during the Harlem Renaissance and in The Crisis.

- Mahatma Gandhi (1869-1948): The preeminent leader of the Indian independence movement against British rule. His philosophy of non-violent resistance was covered in an article in the March 1922 issue of The Crisis.

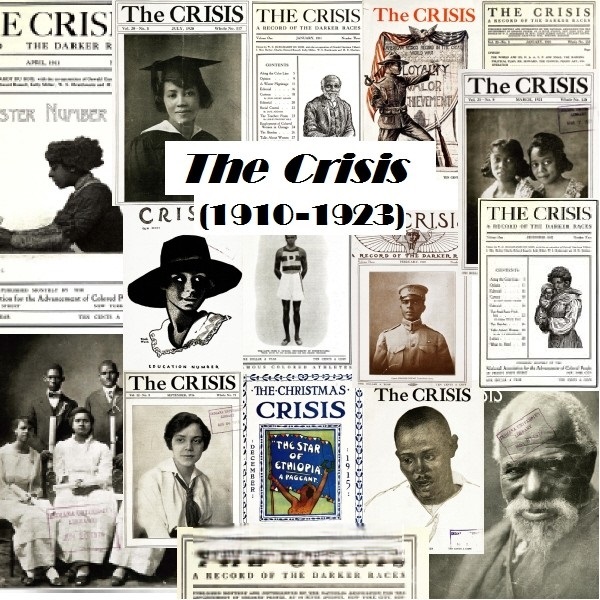

The Crisis – NAACP Magazine (1910 – 1923)

7,800 pages of The Crisis NAACP magazine, every issue published from its first issue, November 1910, through October 1923.

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) established The Crisis magazine in 1910 to provide a magazine for its members. Under the editorship of W.E.B. Du Bois. The Crisis, which Du Bois edited for nearly 25 years, became the premier outlet for black writers and artists.

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois (1868-1963) was a noted scholar, editor, and African-American activist. Du Bois was a founding member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the largest and oldest civil rights organization in America. A brilliant writer and speaker, Du Bois is considered by many to be the outstanding African-American intellectual of his time. His “The Philadelphia Negro” (1899) was the first sociological study of African-Americans. In The Souls of Black Folk (1903), Du Bois took a forceful stand against Booker T. Washington’s policy of accommodation, calling instead for “ceaseless agitation and insistent demand for equality,” and the “use of force of every sort: moral persuasion, propaganda, and where possible even physical resistance.”

In his first editorial written for the magazine Du Bois wrote, “The object of this publication is to set forth those facts and arguments which show the danger of race prejudice, particularly as manifested today toward colored people. It takes its name from the fact that the editors believe that this is a critical time in the history of the advancement of men. …Finally, its editorial page will stand for the rights of men, irrespective of color or race, for the highest ideals of American democracy, and for reasonable but earnest and persistent attempts to gain these rights and realize these ideals.”

The issues included in this “The Crisis” archive includes articles on current events, editorial commentary, essays on culture and history, short stories and poems, reviews, art work, and reports on the achievements of people of color worldwide.

Throughout the years in which Du Bois was the editor of The Crisis, the magazine published the work of many young African-American writers associated with the Harlem Renaissance. Its greatest era as a literary journal was between 1919 and 1926, when Jessie Redmon Fauset was literary editor. Fauset recognized and published the talents of writers such as Arna Bontemps, Langston Hughes, Countee Cullen and Jean Toomer.

The period of time this collection covers coincides with the beginning of an era referred to as the “New Negro Movement.” At this time a mass physical movement of African-Americans from the South to the North and West began in the early twentieth century. Later World War I contributed two effects. The increase in industrial activity generated by the war effort caused many northern businesses to recruit African-Americans living in the South to meet labor demands. Outside the South these workers experienced a measurable increase in wages, working and social conditions. Also, approximately 370,000 African-American men served in the armed forces during World War I. After returning home, many of these men sought the freedoms they were told World War I was fought to preserve.

A political shift was occurring among African-Americans, away from the “accommodationist” approach favored by Booker T. Washington, which was giving way to the more “militant” advocacy of W.E.B. Du Bois.

These forces converged to help create the “New Negro Movement” of the 1920s, which promoted a renewed sense of racial pride, economic independence, and progressive politics. Not only politically but culturally and artistically, as shown by the “Negro Renaissance,” centered in New York City’s Harlem. The Harlem Renaissance, the cultural component of the New Negro Movement, provided the first mass display of African-American cultural self-expression.

he activity of the time is captured in the pages of this collection of The Crisis magazines. Highlights include:

The Crisis Volume 1, Number 1, Page 1 – November 1910

Cover of the first issue of The Crisis

The Crisis Volume 1, Number 2, Page 26 – December 1910

The first major legal case taken by the NAACP was the defense of Pink Franklin. The NAACP took the case in 1910. Franklin was a black South Carolina sharecropper. When Franklin left his employer after receiving an advance on his wages, a warrant was sworn out for his arrest under an invalid state law. Armed policemen arrived at Franklin’s cabin before dawn to serve the warrant without stating their purpose and a gun battle ensued, killing one officer. Franklin was convicted of murder and sentenced to death. The NAACP appealed to South Carolina Governor Martin F. Ansel, and Franklin’s sentence was commuted to life in prison. Eventually, he was set free in 1919.

The Crisis Volume 6, Number 6, Page 298 – October 1913

In 1912, Democrat Woodrow Wilson received more African-American votes than any other previous Democratic presidential candidate. In 1913, President Woodrow Wilson mandated racial segregation into federal government agencies. African-American employees were separated from other workers in offices, restrooms, and cafeterias. Some blacks were demoted or fired.

Oswald Garrison Villard, a writer for The Nation and NAACP treasurer met privately with President Wilson, recommending that he appoint a National Race Commission to counter the new discriminatory policies. When President Wilson refused, the NAACP released this open letter of protest to the press.

The Crisis Volume 10, Number 2, Page 69 – June 1915

When the first exhibitions of the D. W. Griffith film “The Birth of a Nation” look place, the NAACP was alarmed by the content of the film. An idealized portrayal of the Ku Klux Klan as a heroic force. African-American men, played by white actors in blackface, as unintelligent and sexually aggressive toward white women. Birth of a Nation was the first motion picture shown in the White House. Many credit the film as the genesis of the reemergence of the Klu Klux Klan. The NAACP campaign against the film was covered by The Crisis.

The NAACP launched a nationwide campaign to expose the film’s distorted history and attempted to halt its showing. The NAACP appealed to censorship boards and government officials to suppress the film. In localities where authorities refused to act against the film, the NAACP picketed the theaters that showed it. The campaign did not stop the film from being seen in record numbers, but in some cities the most offensive scenes were cut and in others the entire film was banned.

The Crisis Volume 16, Number 2, Page 76 – June 1918

In April 1918, Congressman Leonidas C. Dyer (R-Missouri) introduced an anti-lynching bill in the House of Representatives, based on a bill drafted by NAACP founder Albert E. Pillsbury in 1901. The Dyer Bill provided for the prosecution of lynchers in federal court. State officials who failed to protect lynching victims or prosecute lynchers could face five years in prison and a $5,000 fine. The victim’s heirs could recover up to $10,000 from the county where the crime occurred.

The Crisis Volume 17, Number 5, Page 229 – March 1919

The emergence of a period of Ku Klux Klan existence known as the Second KKK (1915 to 1944) was covered by The Crisis. Soon after The Birth of a Nation was released, a film that mythologized and glorified the first Klan era (1865 to 1874), new Klaverns starting to form.

“Red Summer” – Race Riots – 1919 Race Riots

NAACP field secretary James Weldon Johnson coined the phrase “Red Summer” to describe the wave of racial violence that exploded across the U.S. during the summer and early fall of 1919. During this time period there were race riots in twenty-five cities, most notably in Chicago, Omaha, Washington, D.C., and Longview, Texas. Johnson went to Washington and reported his investigation of the five-day D.C. riot, which erupted on July 19, when white servicemen began assaulting black pedestrians in response to sensationalized newspaper reports of black men attacking white women.

The Crisis Volume 23, Number 5, Page 203 – March 1922

A March 1922 article on Mahatma Gandhi covers the non-cooperation/non-violent theories and practices of the leader of the Indian National Congress.

The Crisis Volume 25, Number 3, Page 103 – January 1923

After a prolonged fight, the House of Representatives passed the Dyer Anti-lynching bill on January 26, 1922 by a vote of 230 to 119, but a year of procedure followed by a filibuster by Southern Democrats defeated the bill in the Senate. This prompted a fierce editorial by Du Bois in the January 1923 issue of The Crisis. Du Bois refutes calling the 21 year fight for anti-lynching federal legislation a loss writing, “Many persons, colored and white, are bewailing the ‘loss’ which Negroes have sustained in the defeat of the Dyer Bill. Rot. We are not the ones who need sympathy. They murder our bodies. We keep our souls. The organization most in need of sympathy, is that century-old attempt at government of, by and for the people, which today stands before the world convicted of failure.”