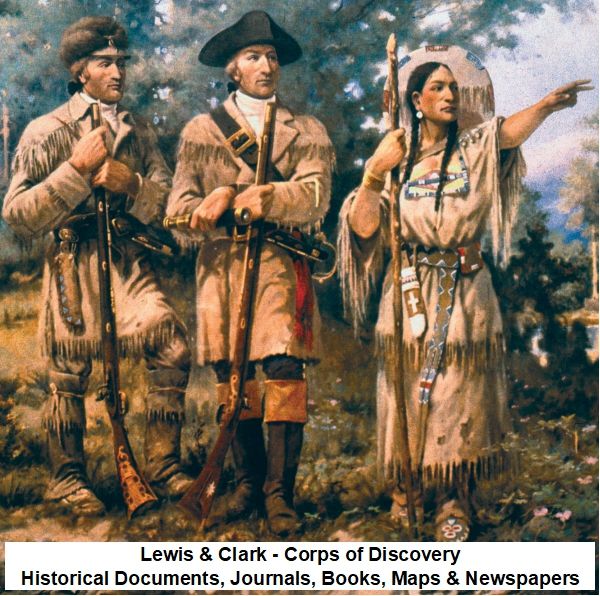

Lewis & Clark – Corps of Discovery Historical Documents, Journals, Books, Maps & Newspapers

$19.50

Description

Lewis and Clark: Expedition Timeline and Characters

Pre-Expedition & Planning (1798 – Early 1804)

- 1798: A map of the Missouri River and vicinity, from St. Charles, Missouri, to the Mandan villages of North Dakota, is created. This map, based on surveys by James Mackay and John Evans, would later be used by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark during their 1804 expedition, with annotations by Lewis.

- December 1792: Captain Vancouver’s companion, Mr. Broughton, travels 100 miles up the Columbia River, reaching a point he names Vancouver. This information is later referenced by Mr. La Cepede in a letter to Thomas Jefferson.

- Spring 1801: Meriwether Lewis is appointed personal secretary to President Thomas Jefferson, marking the beginning of the extensive logistics planning, preparation, and training for the expedition.

- January 18, 1803: President Thomas Jefferson sends a secret message to Congress, proposing a westward expedition.

- February 28, 1803: Thomas Jefferson writes to Casper Wistar, discussing Meriwether Lewis as the leader of the planned expedition.

- April 27, 1803: Thomas Jefferson sends a letter to Lewis, outlining initial instructions for the trip.

- June 20, 1803: Thomas Jefferson sends a detailed letter to Meriwether Lewis, giving specific instructions for the expedition.

- July 15, 1803: Thomas Jefferson sends a letter to Meriwether Lewis, confirming the recent Louisiana Purchase Treaty with France and relaying information from Mr. La Cepede about the Columbia River and the potential for a trade route connecting the continents.

- October 17, 1803: President Thomas Jefferson formally lays before the Senate the conventions with France for the cession of the province of Louisiana to the United States.

- 1803: President Jefferson successfully negotiates the Louisiana Purchase Treaty with France, acquiring the vast Louisiana Territory. Following this, Jefferson initiates the exploration of this new land and the territory beyond the “great rock mountains.”

- Prior to May 1804: Meriwether Lewis selects William Clark as co-commanding captain, a choice approved by President Jefferson, despite Clark not being officially recognized as a Captain by the U.S. Army. Clark is reinstated with the rank of 2nd Lieutenant of the Corps of Artillerists. Lewis, however, consistently refers to Clark as “Captain.”

- Prior to May 1804: A diverse military Corps of Discovery is assembled, consisting of twenty-nine men, including Clark’s black slave, York.

- Prior to May 1804: Sergeant Charles Floyd joins the expedition as one of the first men.

The Expedition (May 1804 – September 1806)

- May 14, 1804: Under the command of Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, the Corps of Discovery sets forth from St. Louis. This is also the day the expedition leaves the Mississippi River.

- May 14 – August 17, 1804: Sergeant Charles Floyd keeps a detailed diary of the expedition.

- August 20, 1804: Sergeant Charles Floyd dies, believed to be from peritonitis caused by a ruptured appendix. He is the only member of the Corps of Discovery to die during the expedition. His grave site is later surveyed by the National Park Service in 1958.

- End of 1804: The expedition reaches the Great Bend of the Missouri.

- End of 1804: While camped near the villages of the Mandan and Minnetaree, the Corps enlists the services of Toussaint Charbonneau and his Shoshone wife, Sacagawea.

- Spring 1805: With high water and favorable weather, the expedition continues its journey, traveling up the Missouri River to present-day Three Forks, Montana. They wisely choose to follow the westernmost tributary, the Jefferson River.

- Spring 1805: This route leads the explorers to the Shoshone Indians, who provide assistance in traversing the Rocky Mountains with horses.

- After crossing the Bitterroot Mountains (1805): The Corps of Discovery constructs canoe-like vessels.

- Late 1805: The expedition travels swiftly downriver to the mouth of the Columbia River.

- Winter 1805-1806: The Corps of Discovery winters at Fort Clatsop, on the present-day Oregon side of the Columbia River, enduring a dismal winter.

- During the expedition (1804-1806): Jean Baptiste Charbonneau is born to Sacagawea.

- Throughout the expedition (1804-1806): Lewis and Clark, along with Sergeants Charles Floyd, Patrick Gass, John Ordway, and Private Joseph Whitehouse, keep detailed journals, documenting the geography, indigenous peoples, natural resources, and daily events. William Clark creates remarkably detailed maps, noting rivers, creeks, significant landscape points, river shorelines, and campsites.

Post-Expedition & Legacy (September 1806 – 1958)

- September 1806: Lewis, Clark, and the remaining members of the Corps of Discovery return to St. Louis. They report their findings to President Jefferson, having traveled over 8,000 miles. They continue to trade with Native American tribes and establish diplomatic relations.

- September 23, 1806: Thomas Jefferson receives a letter from Meriwether Lewis, announcing the safe return of the expedition to St. Louis.

- October 20, 1806: Thomas Jefferson writes a joyful letter to Meriwether Lewis, acknowledging the safe return and expressing his desire to meet the “friend of Mandane” (presumably a Mandan chief who traveled with them).

- 1806: “Message from the President of the United States, Communicating Discoveries Made in Exploring the Missouri, Red River, and Washita, by Captains Lewis and Clark, Doctor Sibley, and Mr. Dunbar; with a Statistical Account of the Countries Adjacent” is published.

- After 1806: Many of Lewis and Clark’s original journals are deposited in the collections of the American Philosophical Society at Jefferson’s urging.

- 1807: Meriwether Lewis is appointed Governor of the Louisiana Territory, stationed in St. Louis. He begins making arrangements to illustrate and publish his journals.

- 1808: William Clark becomes a partner in the St. Louis Missouri River Fur Company.

- 1809: “The Travels of Capts. Lewis and Clarke from St. Louis, by Way of the Missouri and Columbia Rivers, to the Pacific Ocean; Performed in the Years 1804, 1805 & 1806” is published.

- October 1809: Meriwether Lewis commits suicide, facing political difficulties, financial problems, and personal disappointments, and having been unable to publish his journals.

- 1810: William Clark is appointed Governor of the Missouri Territory.

- 1814: The two-volume “History of the Expedition Under the Command of Captains Lewis and Clark” is finally published, prepared by Nicholas Biddle with the help of Clark and George Shannon, using the captains’ and sergeants’ journals.

- 1894: “The New Found Journal of Charles Floyd, a Sergeant under Captains Lewis and Clark” by James Davie Butler is published, containing scans and transcriptions of Floyd’s original journal.

- 1901: “First Across the Continent: The Story of Lewis and Clark Expedition” by Noah Brooks is published, drawing a narrative from excerpts of the original journals.

- 1904: Olin D. Wheeler publishes “The Trail of Lewis and Clark, 1804-1904, Volumes I & II,” following the original trail and noting changes a century later.

- 1904-1905: Reuben Gold Thwaites edits and publishes “Original Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, 1804-1806 Volumes 1-8” from original manuscripts and other sources.

- 1910: Edward Curtis takes a photograph of a Chinook Indian standing on the Columbia River bank at Nihhluidih, the site of a Lewis and Clark landing-place.

- 1938: William Clark dies on September 1.

- 1958: The National Park Service conducts “The National Survey of Historic Sites and Buildings the Lewis and Clark Expedition Sites,” evaluating and listing exceptionally valuable sites related to the expedition, including Three Forks of the Missouri, Lemhi Pass, Travelers Rest, Lolo Trail, and Sergeant Floyd Grave Site and Monument.

- 1959: “Original Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, 1804-1806 Volumes 1-8” is reprinted by Antiquarian Press LTD.

- 1975: Roy E. Appleman publishes “Lewis and Clark Historic Places Associated with their Transcontinental Exploration (1804-06),” detailing the historic background and surveying 41 related sites and buildings.

- 2002: “The U.S. Army and the Lewis and Clark Expedition” is prepared as part of the Army’s contribution to the Bicentennial Commemoration.

- 2003: “Into the Unknown the Logistics Preparation of the Lewis and Clark Expedition” is published, focusing on the planning and preparation stages.

- 2004: The NOAA National Weather Service produces “The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition 1803-1806 Weather, Water & Climate,” describing systematic climatological, hydrological, and meteorological events during the journey.

- 2008: Kathryn Hamilton Wang comments on Olin D. Wheeler’s book in “200 Books, 200 Years.”

Cast of Characters:

- Meriwether Lewis: (1774-1809) President Thomas Jefferson’s personal secretary, chosen by Jefferson to lead the Corps of Discovery Expedition. He co-commanded the expedition with William Clark, keeping detailed journals. After the expedition, he was appointed Governor of the Louisiana Territory in 1807, but faced difficulties and committed suicide in 1809 before his journals could be fully published.

- William Clark: (1770-1838) A frontiersman and draftsman whose abilities were highly respected by Meriwether Lewis, leading Lewis to make him co-commanding captain of the expedition. Although the U.S. Army only recognized him as a 2nd Lieutenant of the Corps of Artillerists, Lewis always called him “Captain.” He kept detailed journals and drew remarkably detailed maps during the expedition. After returning, he was appointed Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the Louisiana Territory (with the rank of Brigadier General of the Militia) in 1807, became a partner in the St. Louis Missouri River Fur Company in 1808, and was appointed Governor of the Missouri Territory in 1810. He helped Nicholas Biddle prepare the expedition journals for publication and died in 1838.

- Thomas Jefferson: (1743-1826) The President of the United States who orchestrated the Louisiana Purchase in 1803 and initiated the Lewis & Clark Expedition. He personally selected Lewis to lead the mission, approved Clark as co-leader, and provided detailed instructions for the expedition, emphasizing the establishment of commercial ties with indigenous peoples and increasing geographical knowledge. He urged the deposit of the expedition’s journals at the American Philosophical Society.

- York: William Clark’s black slave and a member of the Corps of Discovery.

- Toussaint Charbonneau: A French-Canadian fur trader enlisted by the Corps of Discovery near the Mandan and Minnetaree villages.

- Sacagawea: (c. 1788-1812) A Shoshone woman and wife of Toussaint Charbonneau, enlisted by the Corps of Discovery. She was invaluable to the expedition, especially in navigating the Rocky Mountains and interacting with the Shoshone. She gave birth to her son, Jean Baptiste, during the expedition.

- Jean Baptiste Charbonneau: (1805-1866) The son of Sacagawea and Toussaint Charbonneau, born during the Lewis & Clark Expedition.

- Sergeant Charles Floyd: (1782-1804) An American explorer and noncommissioned officer in the U.S. Army, serving as the quartermaster of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. He was one of the first men to join the expedition and was the only member to die during the journey, on August 20, 1804, likely from a ruptured appendix. He kept a journal from May 14 to August 17, 1804.

- Sergeant Patrick Gass: One of the contributors to the journals of the Lewis & Clark Expedition. His journals were used by Nicholas Biddle in preparing the published narrative.

- Sergeant John Ordway: One of the contributors to the journals of the Lewis & Clark Expedition. His journals were used by Nicholas Biddle in preparing the published narrative.

- Private Joseph Whitehouse: One of the contributors to the journals of the Lewis & Clark Expedition.

- Nicholas Biddle: A person persuaded by William Clark to prepare a manuscript for the publication of Lewis’ and Clark’s journals after Lewis’s suicide. He completed the narrative by July 1811, resulting in the 1814 publication.

- George Shannon: An enlisted man on the expedition who assisted Nicholas Biddle in preparing the journals for publication.

- Mr. La Cepede: A correspondent of Thomas Jefferson in Paris, who provided information about Mr. Broughton’s travels up the Columbia River, highlighting its potential for commerce.

- Mr. Broughton: One of the companions of Captain Vancouver, who explored 100 miles up the Columbia River in December 1792.

- James Mackay: One of the surveyors whose work contributed to the 1798 map of the Missouri River and vicinity used by Lewis and Clark.

- John Evans: One of the surveyors whose work contributed to the 1798 map of the Missouri River and vicinity used by Lewis and Clark.

- Dr. Sibley: One of the explorers mentioned in the 1806 “Message from the President of the United States” alongside Lewis and Clark.

- Mr. Dunbar: One of the explorers mentioned in the 1806 “Message from the President of the United States” alongside Lewis and Clark.

- Paul Allen: The individual who prepared the 1814 “History of the Expedition Under the Command of Captains Lewis and Clark” for the press.

- Olin D. Wheeler: (b. 1852) Topographer, author, and railroad executive who, a century after the expedition, followed the Lewis & Clark trail and documented it in his 1904 book, “The Trail of Lewis and Clark, 1804-1904.”

- Reuben Gold Thwaites: (1853-1913) Editor of the 8-volume “Original Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, 1804-1906,” first published in 1904-1905, printing from original manuscripts and other sources.

- James Davie Butler: Author of “The New Found Journal of Charles Floyd, a Sergeant under Captains Lewis and Clark” (1894), which contains scans and transcriptions of Floyd’s original journal.

- Noah Brooks: Author of “First Across the Continent: The Story of Lewis and Clark Expedition,” published in 1901, which drew a narrative from excerpts of the original journals.

- Edward Curtis: Photographer who took a 1910 photograph of a Chinook Indian on the Columbia River bank at a Lewis and Clark landing-place.

- Roy E. Appleman: Author of “Lewis and Clark Historic Places Associated with their Transcontinental Exploration (1804-06)” (1975), which provides historic background and surveys related sites.

- Kathryn Hamilton Wang: Author of “200 Books, 200 Years” (2008), who commented on the value of Olin D. Wheeler’s publication.

- Mr. Dinsmore: Thomas Jefferson’s “principal workman” at Monticello, mentioned in a letter to Lewis in 1806 as someone who could show “tokens of friendship” received from Indian friends.

- William Henry Harrison: His unsigned handwriting appears on the verso of the 1798 map, addressed to Captain William Clark or Captain Meriwether Lewis.

- Mr. Peter Tabeau: Mentioned on the verso of the 1798 map, at the Ricraries.

Lewis & Clark – Corps of Discovery Historical Documents, Journals, Books, Maps & Newspapers

11,335 pages of material related to the Lewis & Clark Corps of Discovery Expedition of 1804 to 1806. Material includes text, historical volumes, and images of original documents and maps. The collection features Thomas Jefferson papers & correspondences, transcriptions of the journals of Lewis and Clark and others on the Expedition, books, maps, newspapers and more.

All computer recognizable text, transcriptions, reproduced printed text, and description sheets in the collection are searchable.

In 1803, President Thomas Jefferson was successful in a moving an illustrious foreign diplomacy endeavor through the United States Senate: the purchase of the Louisiana Territory from France. After the Louisiana Purchase Treaty was signed, Jefferson initiated an exploration of the newly purchased land and the territory beyond the “great rock mountains” in the West. The objectives of the mission were the establishment of commercial ties with the indigenous people of the Far West and an increase in the knowledge of the region’s geography. Jefferson chose his personal secretary, Meriwether Lewis to lead the expedition.

Lewis in turn solicited the help of William Clark, whose abilities as a draftsman and frontiersman were stronger than those of Lewis. Lewis so respected Clark, that he made him a co-commanding captain of the Expedition, even though Clark was never recognized as such by the government. President Jefferson approved Lewis’ choice of Clark as the co-leader of the planned expedition to the Pacific. The U.S. Army would not reinstate Clark with his former rank of Captain. He received the rank of 2nd Lieutenant of the Corps of Artillerists. Lewis always called Clark by the title of “Captain” and never told the members of the Corps of Discovery to do otherwise. Together they collected a diverse military Corps of Discovery that would be able to undertake a two-year journey to the great ocean.

Under the command of Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, the Corps of Discovery set forth from St. Louis on May 14, 1804. The party originally consisted of twenty-nine men, including Clark’s black slave York. In the next twenty-eight months, the Corps of Discovery would travel more than 8,000 miles through unfamiliar terrain inhabited by an array of indigenous peoples. Jefferson hoped that Lewis and Clark would find a water route linking the Columbia and Missouri rivers. This water link would connect the Pacific Ocean with the Mississippi River system, thus giving the new western land access to port markets out of the Gulf of Mexico and to eastern cities along the Ohio River and its minor tributaries. At the time, American and European explorers had only penetrated what would become each end of the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Both captains kept detailed journals that depicted a culturally and geographically diverse Western landscape, that was rich with natural resources. Their descriptions of vast populations of fur-bearing mammals would spur the extension of the American fur trade into the upper reaches of the Missouri River.

The expedition made it as far as the Great Bend of the Missouri by the end of 1804. While camped near the villages of the Mandan and Minnetaree, the Corps enlisted the services of Toussaint Charbonneau and his Shoshone wife Sacagawea. The following year, the expedition journeyed up the Missouri, across the Rocky Mountains, and down the Columbia River to the Pacific Ocean. When the spring of 1805 brought high water and favorable weather, the Lewis and Clark Expedition set out on the next leg of its journey. They traveled up the Missouri to present-day Three Forks, Montana, wisely choosing to follow the western-most tributary, the Jefferson River. This route delivered the explorers to the doorstep of the Shoshone Indians, who were skilled at traversing the great rock mountains with horses. Once over the Bitterroot Mountains, the Corps of Discovery shaped canoe-like vessels that transported them swiftly downriver to the mouth of the Columbia, where they wintered (1805-1806) at Fort Clatsop, on the present-day Oregon side of the river. At the newly erected Fort Clatsop, the party suffered through a dismal winter. The following year all members of the Corps of Discovery returned along roughly the same route. During the journey only one person, Sergeant Charles Floyd, lost his life, while another, Jean Baptiste Charbonneau, was born to Sacagawea.

With journals in hand, Lewis, Clark, and the other members of the Expedition returned to St. Louis by September 1806 to report their findings to President Jefferson. Along the way, they continued to trade what few goods they still had with the Indians and set up diplomatic relations with the Indians. Additionally, they recorded their contact with Indians and described the shape of the landscape and the and the animals in western North America, new to the white man.

In doing so, they fulfilled many of Jefferson’s wishes for the Expedition. Along the way, William Clark drew a series of maps that were remarkably detailed, noting and naming rivers and creeks, significant points in the landscape, the shape of river shore, and spots where the Corps spent each night or camped or portaged for longer periods of time. Later explorers used these maps to further probe the western portion of the continent.

Meriwether Lewis in 1807 was appointed Governor of the Louisiana Territory and stationed in St. Louis. Lewis had made many of the arrangements needed to illustrate and publish his journals of the expedition, but he was never able to work on or provide the manuscript. By 1809, he faced political difficulties and financial problems, as well as family and personal disappointments. Lewis committed suicide in October of 1809.

William Clark was appointed by President Jefferson to be Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the Louisiana Territory with the rank of Brigadier General of the Militia. In 1808, Clark became one of the partners in the St. Louis Missouri River Fur Company. Clark was appointed Governor of the Missouri Territory in 1810. William Clark died on September 1, 1838.

Collection Includes:

Thomas Jefferson Papers & Correspondences

266 pages of transcriptions and images of Thomas Jefferson papers and correspondences dealing with the Lewis & Clark Expedition. Included are Thomas Jefferson’s January 18, 1803, secret message to Congress proposing a westward expedition, a February 28, 1803, letter to Casper Wistar discussing Meriwether Lewis as leader of the expedition, an April 27, 1803, letter to Lewis outlining instructions for the trip, and a June 20, 1803 letter from Thomas Jefferson to Meriwether Lewis giving Lewis detailed instructions for his trip.

Journals of Lewis and Clark

853 pages of text transcription copied from the writings in the Journals of Lewis and Clark, written mostly by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, 1804-1806. Other contributors to the journals are Sergeants Charles Floyd, Patrick Gass, John Ordway, and Private Joseph Whitehouse. Includes transcriptions of the raw journal entries made between May 14, 1804, the day the expedition left the Mississippi River, to September 26, 1806, a day or two after they arrived back in St. Louis. Includes all possible Journal entries of Lewis and Clark. Most of the “courses and distances” and “celestial observations” have been omitted. These transcripts of the journals include their original misspellings, period spellings, and abbreviations.

After the Corps of Discovery disbanded in 1806, many of Lewis and Clark’s journals were deposited in the collections of the American Philosophical Society at Jefferson’s urging. Some editors of the journals argued that the excellent condition of these journals indicates that they were fair copies made after the end of the expedition in September of 1806, and prior to Jefferson’s receiving them at the end of the year.

However, others suggest that the story is more complex. The American Philosophical Society collection consists of 18 small notebooks, approximately 4 by 6 inches of the type commonly used by surveyors in field work. Thirteen of these are bound in red Morocco leather, four in boards covered in marbled-paper, and one in plain brown leather, and there are loose pages and rough notes as well. The available evidence suggests that Lewis and Clark carried their notebooks sealed in tin boxes that were intended to protect the relatively fragile journals from the elements. If nothing else, with Jefferson’s advising, that the journals were considered invaluable as the only reliable record of data gathered on the expedition. It seems likely, therefore, that great care would be taken in their preservation.

From a close examination of the journals and sets of loose notes, noted Lewis and Clark historian Gary Moulton, among others, has concluded that Lewis and Clark often worked from rough notes compiled daily, then periodically transcribed these into more polished form in the bound volumes, however in most cases, the time between taking the notes and transcribing them must have been very brief. On many occasions, the explorers clearly wrote directly into the bound volumes. The journals contain huge volumes of data, going beyond geographical notes and records of temperature and weather.

Original Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, 1804-1806 Volumes 1-8

3,322 pages in 8 volumes first published 1904-1905, reprinted by Antiquarian Press LTD., New York in 1959.

Abstract: Printed from the original manuscripts in the Library of the American Philosophical Society and by direction of its Committee on Historical Documents, together with manuscript material of Lewis and Clark from other sources, including notebooks, letters, maps, etc., and the journals of Charles Floyd and Joseph Whitehouse. Edited, with Introduction, Notes, and Index, by Reuben Gold Thwaites, LL.D.

History of the Expedition of Captains Lewis and Clark Volumes 1 & 2 (1814)

A digitally reproduced copy of an original 1814 printing of the book: History of the Expedition Under the Command of Captains Lewis and Clark, to the Sources of the Missouri, Thence Across the Rocky Mountains and Down the River Columbia to the Pacific Ocean: Performed During the Years 1804-5-6 by Order of the Government of the United States/Prepared for the Press by Paul Allen; Volumes 1 & 2. With a preface written by Thomas Jefferson.

After the suicide of Lewis, Clark, who felt that he was not up to the task, persuaded Nicholas Biddle to prepare a manuscript for publication of both Lewis’ and Clark’s journals from the expedition. With the help from Clark and George Shannon, one of the enlisted men on the expedition, the work took Biddle two years to complete. Royalties from the sale of the published journals were to go to Clark, but he never received a penny. Using the captains’ original journals and those of Sergeants Gass and Ordway, Biddle completed a narrative by July 1811. After delays with the publisher, a two-volume edition of the Corps of Discovery’s travels across the continent was finally available to the public in 1814. More than twenty editions appeared during the nineteenth century, including German, Dutch, and several British editions.

The Trail of Lewis and Clark, 1804-1904, Volumes I & II by Olin D. Wheeler, (1904)

Kathryn Hamilton Wang commented in her book “200 Books, 200 Years” (2008) on this book, “Although dated, the value of this publication lies with Wheeler’s travels along the Trail a mere 100 years after the Corps’ journey.”

A digital reproduction of the book: The Trail of Lewis and Clark, 1804-1904: A Story of the Great Exploration Across the Continent in 1804-1806, with a Description of the Old Trail Based Upon Actual Travel Over It, and of the Changes Found a Century Later. New York: Putnam’s, 1904.

Topographer, author, and railroad executive Olin D. Wheeler used the journals of Lewis & Clark as a guide to follow their trail. He followed the Lewis & Clark trail giving insight to the original journey, noting the important and interesting places visited by Lewis and Clark, then by tourists and travelers 100 years later. Volumes contains photographs, sketches, and maps.

Message from the President of the United States, Communicating Discoveries Made in Exploring the Missouri, Red River, and Washita, by Captains Lewis and Clark, Doctor Sibley, and Mr. Dunbar, with a Statistical Account of the Countries Adjacent

132-page printed copy published in 1806 of “Message from the President of the United States, Communicating Discoveries Made in Exploring the Missouri, Red River, and Washita, by Captains Lewis and Clark, Doctor Sibley, and Mr. Dunbar; with a Statistical Account of the Countries Adjacent” (New-York: Printed by Hopkins and Seymour, 1806).

The Original Journal of Sergeant Charles Floyd

Contains scans of the original journal and their transcription as found in the book, “The New Found Journal of Charles Floyd, a Sergeant under Captains Lewis and Clark, by James Davie Butler (1894).

The Floyd diary dates from May 14 through August 17, 1804. Charles Floyd (1782 – August 20, 1804) was an American explorer, a noncommissioned officer in the U.S. Army, and the quartermaster of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. A native of Kentucky, he was a son of Robert Clark Floyd, a nephew of James John Floyd, a cousin of Virginia governor John Floyd, and possibly a relative of William Clark. He was one of the first men to join the expedition, and the only member of the Corps of Discovery to die during the expedition. It is believed he died from peritonitis caused by a ruptured appendix.

First Across the Continent

An electronic book and text of First Across the Continent: The Story of Lewis and Clark Expedition, by Noah Brooks. Published in 1901, Brooks draws a narrative of the expedition using excerpts from the original journals of the expedition.

The Travels of Capts. Lewis and Clarke from St. Louis, by Way of the Missouri and Columbia Rivers, to the Pacific Ocean; Performed in the Years 1804, 1805 & 1806 (1809)

Complete title, “The Travels of Capts. Lewis & Clarke, by order of the government of the United States performed in the years 1804, 1805, & 1806: being upward of three thousand miles, from St. Louis, by way of the Missouri, and Columbia Rivers, to the Pacifick Ocean: containing an account of the Indian tribes, who inhabit the western part of the continent unexplored, and unknown before : with copious delineations of the manners, customs, religion, &c. of the Indians.”

Timeline

A detailed 22-page timeline of the history of the Lewis & Clark expedition.

Maps

8 maps created before and after the Lewis & Clark expedition. Includes maps used by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark in their 1804 expedition up the Missouri River, with annotations in ink by Meriwether Lewis. Also includes maps made after the expedition utilizing information gained by Corps of Discovery.

National Park Service Documents

1,178 pages of material from the Department of the Interior’s National Park Service covering the history of the Corps of Discovery and sites related to Lewis & Clark and the sites’ historical preservation. Highlights include:

Lewis and Clark Historic Places Associated with their Transcontinental Exploration (1804-06) by Roy E. Appleman (1975)

This book contains 242 pages relaying the historic background of the Lewis and Clark Expedition and 105 pages of survey of 41 Historic sites and buildings related to the Expedition.

The National Survey of Historic Sites and Buildings the Lewis and Clark Expedition Sites (1958)

The 1958, 177-page report titled, “United States Department of the Interior National Park Service The National Survey of Historic Sites And Buildings 1958 survey of several sites including: Three Forks of the Missouri, Montana; Lemhi Pass, Montana-Idaho; Travelers Rest, Montana; Lolo Trail, Idaho; Sergeant Floyd Grave Site and Monument, Iowa.”

Abstract: This study represents the work of the National Park Service field staff assigned to The National Survey of Historic Sites and Buildings. In the process of evaluating the sites treated in the several themes, the Consulting Committee for the Survey and the Advisory Board on National Parks, Historic Sites, Buildings, and Monuments have screened the findings of the field staff. Some sites recommended by the field staff for classification of exceptional value have been eliminated, and in a few cases sites and buildings have been added to the lists of exceptionally valuable sites.

Newspapers

217 full newspaper sheets dating from 1803 to 1827 with coverage related to the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

Additional Books, Reports, and Monographs

An additional 18 books, reports, theses, and monographs comprising 2,463 pages on the Expedition. Highlights include:

NOAA National Weather Service – The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition 1803-1806 Weather, Water & Climate (2004)

A 123-page report produced in 2004 by the National Weather Service, describes the systematic climatological, hydrological, and meteorological events during the Lewis & Clark journey.

Into the Unknown the Logistics Preparation of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (2003)

Abstract: Captain Meriwether Lewis’s task was to equip and man a party to traverse the unmapped middle third of the United States. Most studies of the expedition begin with the party’s departure from Camp Dubois in the spring of 1804. This starting point ignores the important logistics planning, preparation and training that commenced with Lewis’s appointment as personal secretary to President Thomas Jefferson in the spring of 1801. Under President Jefferson’s watchful eye Lewis conducted extensive preparations at Washington D.C., Harper’s Ferry, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, and St. Louis. Expedition journals, personal correspondence and equipment receipts are used to provide insight into the effectiveness of the endeavor’s logistics support plan. The study concludes by identifying four themes evident in the expedition’s planning and execution that are useful to modern logisticians: the value of innovation, the significance of support received from indigenous peoples, the employment of civilian contractors and the seemingly obligatory discovery that transportation capabilities rarely meet requirements.

The U.S. Army and the Lewis and Clark Expedition (2002)

Abstract: The U.S. Army and the Lewis and Clark Expedition, prepared as part of the Army’s contribution to the observance of the Lewis and Clark Bicentennial Commemoration (2003-2006), is an engaging account of a stirring and significant event in American military heritage. While most Americans have some inkling of the importance of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, officially designated the “Corps of Volunteers for Northwestern Discovery,” relatively few recognize that it was an Army endeavor from beginning to end.