Civil War: Surgeon General Photos & Surgical Cases

$19.50

Description

The Army Medical Museum: Civil War Cases

- 1861-1865: The American Civil War: This is the overarching conflict during which the events described in the source occur.

- Early in the War: Regimental surgeons and their mates are the primary medical personnel, and a centralized medical system is lacking.

- 1862: Establishment of the Army Medical Museum: Surgeon General William Hammond of the Union Army founds the Army Medical Museum to collect and study medical information from the war.

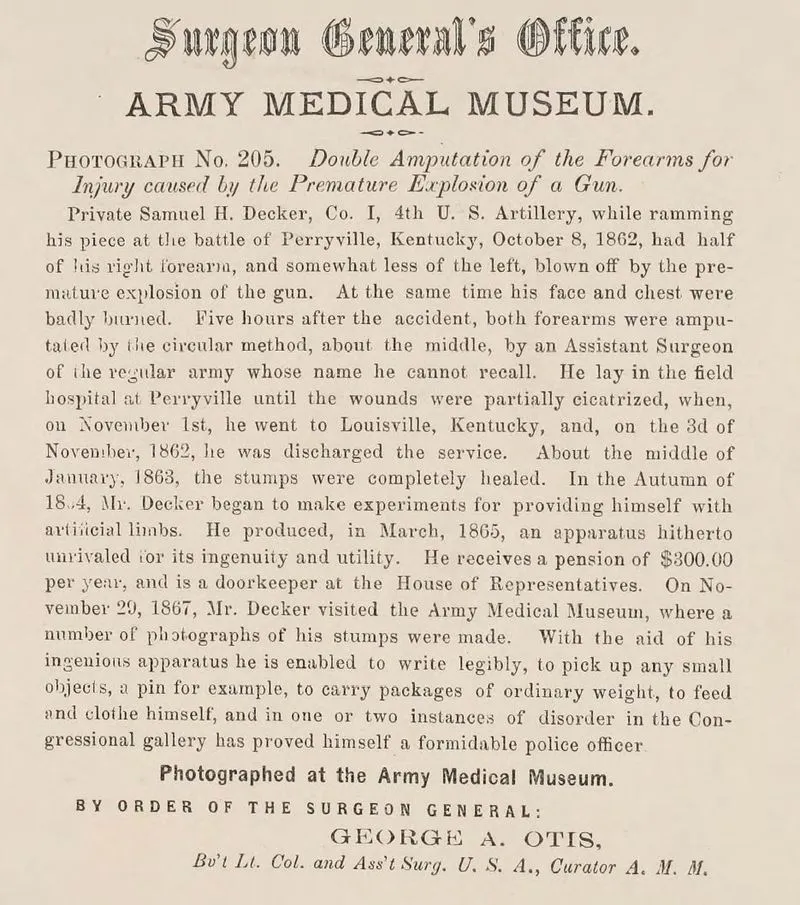

- 1862: Battle of Perryville, Kentucky: Private Samuel H. Decker loses his forearms in a gun accident during the battle. His forearms are amputated shortly after.

- May 2, 1863: Battle of Chancellorsville: Captain Robert Stolpe is wounded by a musket ball, which passes through his chest and diaphragm and into his alimentary canal. He is treated at various field hospitals, and the ball is eventually voided.

- July 2, 1863: Battle of Gettysburg: Major General D.E. Sickles’ right leg is shattered by a cannonball. He is quickly moved to a sheltered area where his leg is amputated.

- 1864: George Alexander Otis becomes curator of the Army Medical Museum. Otis supervises the compilation and photography of specimens.

- 1864 – 1865: Samuel Decker begins experimenting with artificial limbs.

- March 1865: Samuel H. Decker creates a set of unique and effective artificial limbs.

- 1865-1868: William Bell serves as the Chief Photographer for the museum and photographs many of the cases and specimens.

- November 20, 1867: Samuel H. Decker visits the Army Medical Museum, where his amputated stumps are photographed.

- Post-War:

- The Army Medical Museum continues to compile medical cases and specimens, including civilian cases deemed relevant.

- The photographic and narrative documentation is gathered and organized for publication.

Cast of Characters:

- William Hammond: Surgeon General of the Union Army. He founded the Army Medical Museum in 1862, directing medical officers to send specimens and data to it for study.

- John Hill Brinton: First curator of the Army Medical Museum. He visited battlefields and solicited contributions from doctors throughout the Union Army.

- George Alexander Otis: Assistant Surgeon, U.S.A. and the second curator of the Army Medical Museum, succeeding Brinton in 1864. He supervised the compilation and photography of the collection of cases and specimens.

- William Bell: Chief Photographer for the Army Medical Museum from 1865 to 1868. He photographed many of the subjects and specimens in the collection. He is also known for his later images of the American West.

- D.E. Sickles: Major General in the U.S. Volunteers. He was wounded at Gettysburg, losing his right leg due to a cannonball. His case is documented in the collection and the leg bone was given to the museum by him.

- Thomas Sim: Surgeon in U.S. Volunteers and Medical Director of the 3rd Army Corps. He performed the amputation on General Sickles’ leg on the battlefield at Gettysburg.

- Robert Stolpe: Captain in Company A, 29th New York Volunteers. He suffered a severe chest wound at the Battle of Chancellorsville when a musket ball passed through his chest, diaphragm, and into his alimentary canal. He survived the injury after a long treatment process.

- Tomaine: Surgeon who took over Stolpe’s care after his transfer to a base hospital. He removed a ligature from the base of a protruding part of Stolpe’s lung.

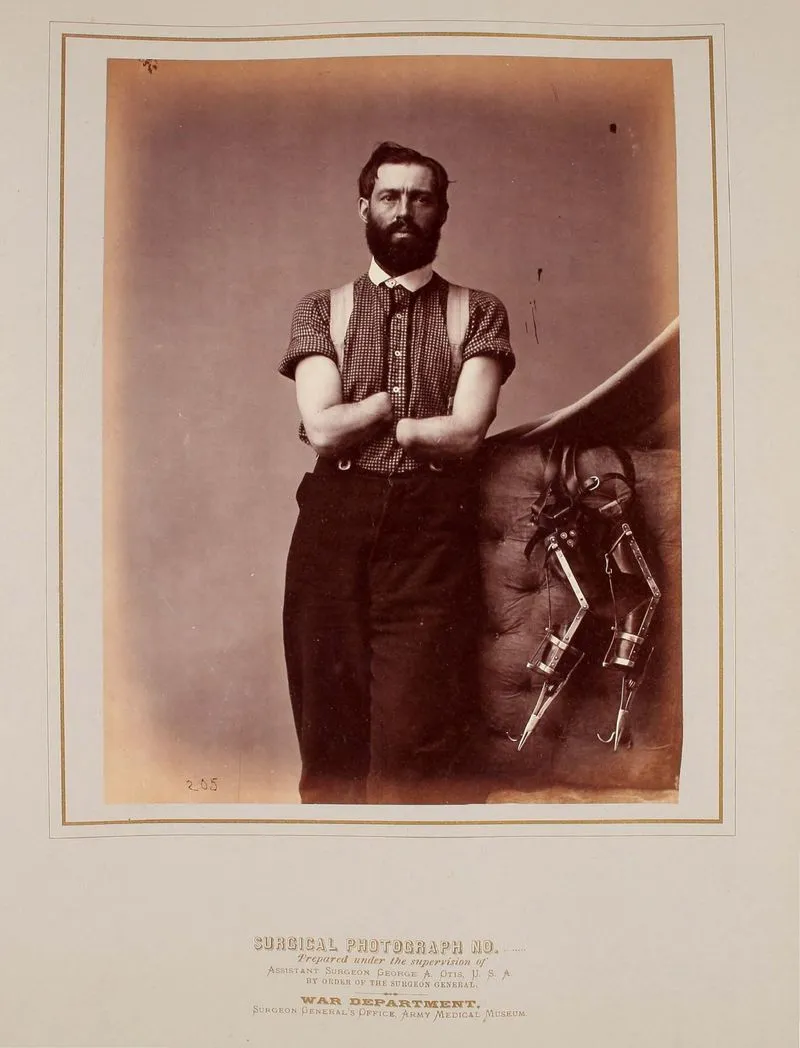

- Samuel H. Decker: Private in Co. I, 4th U. S. Artillery. He lost both forearms in a gun accident at the Battle of Perryville. He designed his own prosthetic limbs and later worked as a doorkeeper for the House of Representatives. His case, his ingenuity, and his prosthetic device are all documented in the medical collection.

Civil War: U.S. Surgeon General Photographs and Histories of Surgical Cases and Specimens

This collection consists of 660 pages across six volumes featuring images commissioned by the U.S. surgeon general along with summaries of injuries from the Civil War.

The photos included depict graphic medical scenes of injuries and anatomy, which may not be appropriate for every viewer. The reproductions of these volumes are presented without edits.

These images challenge the romanticized views often associated with the Civil War, revealing the true experiences, wounds, and sacrifices of soldiers from both the Union and Confederate sides.

The National Museum of Health and Medicine reports that out of approximately 3 million soldiers and sailors who fought in the Civil War, around 618,000 lost their lives, with nearly 400,000 fatalities attributed to disease. This death rate represented almost 2% of the total population at the time. Of the 79% of combatants who made it through the war, nearly half a million returned home with permanent disabilities or injuries.

The photographs and illustrations in this collection are striking. They clearly depict the severe impact of new warfare technologies from the Civil War on human bodies. Detailed case histories written by Army Medical Museum staff accompany each photo, documenting the names and ranks of soldiers, the battles where injuries occurred, dates, treatment details, and the final outcomes. Compiled in the 1860s, this material offers extensive medical and biographical insights for historians and others interested. The content in these volumes was created under the guidance of the Surgeon General’s Office, led by Brevet Lieutenant Colonel George A. Otis, an Assistant Surgeon in the U.S.A. and the curator of the Army Medical Museum. Established in 1862 by Union Army Surgeon General William Hammond, the Army Medical Museum served as a hub for medical knowledge gathered from Union surgeons.

Surgeon General Hammond instructed field medical officers to gather “specimens of morbid anatomy along with projectiles and foreign objects that were removed” and send them to the newly established museum for examination. The first curator of the Museum, John Brinton, traveled to battlefields in the mid-Atlantic region and requested donations from physicians across the Union Army. During and following the war, the Museum staff documented the injuries of soldiers through photographs, showcasing the impact of gunshot wounds and the outcomes of amputations and other surgical interventions.

This collection features many anatomical specimens collected by Dr. John Hill Brinton for the Army Medical Museum (now known as the National Museum of Health and Medicine), which are photographed here. The organization and photography of these subjects were overseen by Dr. George Alexander Otis, who took over the curator role from Brinton in 1864. William Bell, renowned for his later photographs of the American West, worked as the Chief Photographer for the museum from 1865 to 1868, capturing many portraits and specimen images himself.

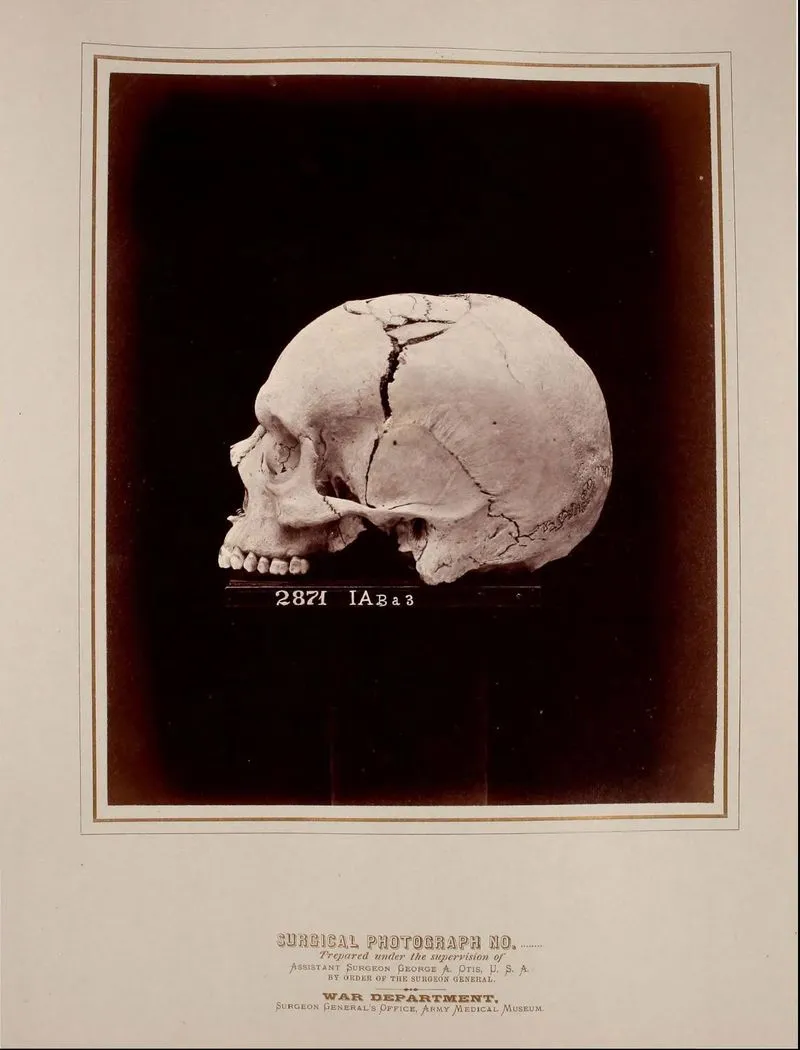

Included in this collection are 300 case narratives, 286 photographs of patients and specimens, and 14 illustrations. The cases and specimens were selected by museum staff from the extensive materials available at the Army Medical Museum, highlighting the most significant examples for research purposes. The six volumes include mounted albumen photographic prints along with detailed case histories. The collection, titled “Photographs of Surgical Cases and Specimens,” provides extensive visual records of patients who experienced traumatic injuries during and shortly after the Civil War. Most individuals depicted were soldiers from both the Union and Confederate armies, but the later volumes, published post-war, added civilian cases deemed relevant to the collection. This work features both portraits and specimen photography, along with a few photographs of reproduced drawings and paintings. A significant number of specimens demonstrate fractures or necrotic bone deterioration resulting from shrapnel or gunshot injuries.

During the Civil War, approximately 350,000 extremity wounds were inflicted on Union and Confederate soldiers, leading to around 60,000 amputations.

Surgery in the 1860s

Prior to the Civil War, military medical care fell under the responsibility of regimental surgeons and their assistants. The war prompted efforts to create a centralized medical system. By today’s standards, the treatment options available for diseases and injuries were quite rudimentary. Medical departments, often lacking adequate supplies and personnel, functioned within the constraints of battlefield hospitals situated just outside the range of enemy fire.

Despite the best efforts of medical staff to provide prompt and effective care to the wounded, severely injured soldiers frequently went without any treatment for one to two days following significant battles. During the Civil War, notable advancements took place as improvements in medical science, communication, and transportation facilitated more effective centralized collection and treatment of casualties. Even with limited surgical expertise and poor sanitary conditions, the survival rate for those who underwent surgery during the war was higher compared to past conflicts.

Amputation was not the sole option available for treatment; surgeons also removed bullets, treated fractured skulls, reconstructed damaged facial features, and excised broken bone sections. The National Museum of Health and Medicine reports that Union surgeons recorded nearly 250,000 wounds from bullets, shrapnel, and other projectiles, while fewer than 1,000 wounds were attributed to sabers and bayonets.

Amputations

Surgeons during the Civil War often had to resort to amputating limbs to manage severe arm and leg injuries. The intricate wounds inflicted by bullets and shrapnel often became contaminated with foreign objects. The feared minié ball could mutilate flesh, splinter bones, and devastate tissue beyond repair. Bone fragments, dirt, torn fabric, and bacteria contributed to infections.

Cleaning these complex wounds required significant time and frequently proved ineffective. Due to shattered bones and resulting infections, surgeons often had no choice but to perform amputations. This procedure transformed a complicated wound into a simpler one located above the original injury. Surgical guidelines indicated that amputations should be conducted within the first two days after an injury. The mortality rate from “primary amputations” was lower than for those performed after infection set in. Union surgeons carried out nearly 30,000 amputations, and Confederate surgeons are estimated to have performed a similar number.

The management of abdominal injuries typically included pushing back any exposed organs and stitching the wound closed. Injuries to the chest were treated by cleaning the area and suturing it. Patients were not allowed to eat because leakage from the intestines contaminated the area. Opium was frequently given to stop digestive activity. Nearly 90 percent of abdominal wounds reported by Union surgeons were fatal.

Notable cases include:

Major General D.E. Sickles, a U.S. Volunteer, was injured on the second evening of the Gettysburg battle when a twelve-pound cannonball shattered his right leg. At that moment, he was riding a horse without assistance, but he managed to calm his startled horse and dismount alone. According to the details provided with the case photograph, “he was moved to a nearby sheltered ravine where Surgeon Thomas Sim, Medical Director of the 3rd Army Corps, performed an amputation low on the thigh. He was then transported further back and the next day moved to Washington.

The stump healed very quickly. By July 16th, he was able to ride in a carriage. By early September 1863, the stump had fully healed, and he could ride a horse again. General Sickles donated the specimen to the Army Medical Museum, and his staff surgeon, Dr. Sim, provided the details of the case.” Captain Robert Stolpe, who served in Company A of the 29th New York Volunteers, suffered injuries during the Battle of Chancellorsville on May 2, 1863. The account describes that a musket ball, shot from approximately one hundred fifty yards away, penetrated the eighth intercostal space on his left side, about nine and a half inches to the left of the end of the xiphoid process, and broke the ninth rib. It appears that the ball did not injure the lung directly; instead, it passed through the diaphragm and into part of the digestive system. Captain Stolpe managed to walk a mile and a half to a field hospital.

Upon examining his wound, the surgeons discovered that part of his lung was protruding, roughly the size of a small orange, which they were unable to push back inside. They made the incision larger, but still could not reposition the extruded lung. On May 3rd, the field hospital where he was located came under enemy fire. He then walked another half mile to safety, where he was placed in an ambulance and transported across the Rappahannock River at United States Ford to a base hospital. At this location, more unsuccessful attempts were made to reduce the herniated lung, leading to a ligature being applied around its base and tightened. A day or two later, he was treated by Surgeon Tomaine, who removed the ligature.

A small piece of necrotic lung tissue detached, revealing a clean granulating area underneath. The musket ball was expelled from his body during a bowel movement on May 7th. On May 8th, Surgeon John H. Brinton, U.S. Vols., visited him and found him walking around the ward while smoking a cigar. He exhibited no significant general symptoms: there was no cough, difficulty breathing, or abdominal pain; his bowel movements were normal, and he had a good appetite. The lung portion that was protruding had become fibrous… Private Samuel H. Decker, Company I of the 4th U.S. Artillery, was photographed on November 29, 1867.

His hands were severely injured in a gun mishap during the Perryville battle in Kentucky in 1862. To accommodate his disability, Decker created his own prosthetic devices. He later took on the role of doorkeeper for the House of Representatives. The description accompanying his photograph explains that “while loading his artillery piece at the battle of Perryville on October 8, 1862, he lost half of his right forearm and a little less of his left due to a premature gun explosion. Additionally, his face and chest suffered significant burns. Five hours following the incident, both of his forearms were amputated in the middle using the circular method by an Assistant Surgeon of the regular army, whose name he can’t remember…” “In the fall of 1864, Mr. Decker started experimenting with ways to create artificial limbs for himself.

By March 1865, he developed a device noted for its cleverness and functionality. He currently receives an annual pension of $300.00 and serves as a doorkeeper in the House of Representatives. On November 20, 1867, Mr. Decker went to the Army Medical Museum, where several photos of his amputated limbs were taken. Thanks to his innovative device, he can write clearly, pick up small items like pins, carry moderately heavy packages, and take care of his personal needs. In a few instances of disturbances in the Congressional gallery, he has also shown himself to be an effective security officer.”

Related products

-

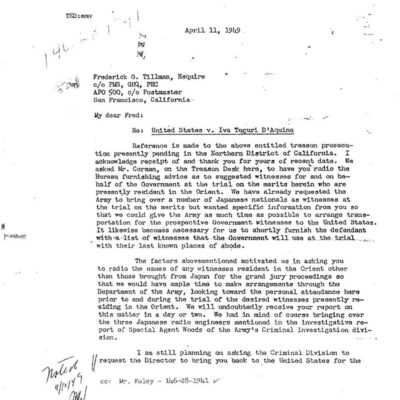

Tokyo Rose: Department of Justice Prosecution Files

$19.50 Add to Cart -

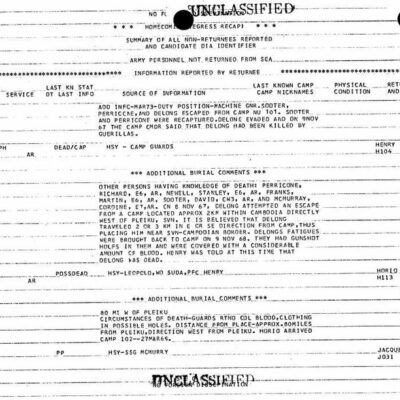

Vietnam War: POW/MIA Summary of All Reported Non-Returnees

$19.50 Add to Cart -

World War II Manual on Weapons for Jungle Warfare (1944)

$1.99 Add to Cart -

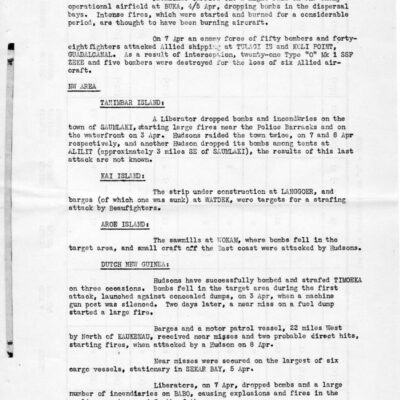

World War II: Australian Military Weekly Intelligence Reports 1943-44

$3.94 Add to Cart