Civil War Reports by the U.S. Congress Joint Committee

$19.50

Description

The Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War

- July 21, 1861: The First Battle of Bull Run (also known as First Manassas) takes place. Members of Congress, along with civilians, observe the battle. The Union army suffers a significant defeat. This is the “Picnic Battle” and directly leads to calls for Congressional investigation

- October 1861: Senator Edward D. Baker, a friend of President Lincoln, is killed at the Battle of Ball’s Bluff, another Union loss.

- December 5, 1861: Senator Zachariah Chandler introduces a resolution to investigate the battles at Bull Run and Ball’s Bluff. Other senators call for a broader inquiry into the conduct of the war.

- December 9, 1861: The Senate passes a resolution creating the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War.

- December 10, 1861: The House passes the resolution, creating a joint committee comprised of three senators and four representatives with the power to “inquire into the conduct of the present war and to send for persons and papers.”

- December 17, 1861: Senator Chandler defers chairing the committee to his friend, Senator Benjamin Wade, due to Wade’s legal background.

- 1861-1865: The Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War meets 272 times over the course of the war.

- Early 1862: The Committee begins investigations, driven in part by newspaper accounts of the actions of commanders. They leak the written statement of General John C. Frémont to the New York Daily Tribune.

- November 1862: President Lincoln relieves Major General George McClellan from command of the Army of the Potomac.

- 1863: The Committee issues its first report in three parts:

- Part 1: Covers the Army of the Potomac.

- Part 2: Covers the Union’s 1861 Eastern Theater losses at First Bull Run and Ball’s Bluff.

- Part 3: Covers the war’s Western Theater.

- 1864: The Committee issues its second report in two parts:

- Part 1: Focuses on the Fort Pillow Massacre and the mistreatment of United States Colored Troops.

- Part 2: Focuses on the condition of returned Union soldiers after their imprisonment in Confederate POW camps.

- January 20, 1864-May 22, 1865: The Committee maintains a journal of its activities.

- 1865: The Committee issues its third report in three parts covering:

- The Mine Crater incident during the Siege of Petersburg.

- The Fort Pillow episode.

- Military expeditions at Fort Fisher and up the Red River.

- Extensive testimony on subjects including ordnance, contracts to supply ice, turreted Monitor-class warships, and the massacre of friendly Cheyenne Indians at Sand Creek.

- May 22, 1865: The Joint Committee issues its final report.

- 1866: A two-volume supplemental report is published, including reports from various Union generals, including W.T. Sherman, George H. Thomas, John Pope, J.S. Foster, A. Pleasanton, E.A. Hitchcock, P.H. Sheridan, and James B. Ricketts.

Cast of Characters

- Benjamin Wade (R-OH): Senator from Ohio, Chairman of the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War. A Radical Republican, he was critical of President Lincoln’s war policies and considered him “a fool.” Believed his legal background made him well-suited for chairing the committee. He was also a witness to the retreat from Bull Run, and threatened soldiers to stop fleeing.

- Zachariah T. Chandler (R-MI): Senator from Michigan, instrumental in the creation of the Joint Committee. Initially proposed the investigation of Bull Run and Ball’s Bluff. He deferred to Senator Wade for committee leadership. He was also a witness to the retreat from Bull Run, and tried to block the road to stop the retreat.

- John Covode (R-PA): Republican Representative on the committee.

- Benjamin Loan (R-MO): Replaced John Covode on the committee.

- Daniel Gooch (R-MA): Republican Representative on the committee.

- Andrew Johnson (D-TN): Senator from Tennessee and committee member. Later became President of the United States following Lincoln’s assassination. He was eventually replaced on the committee.

- Joseph Wright (Unionist-IN): Replaced Andrew Johnson on the committee.

- Benjamin Harding (D-OR): Replaced Joseph Wright on the committee.

- George Julian (R-IN): Republican Representative on the committee.

- Moses Odell (D-NY): Democratic Representative on the committee.

- Edward D. Baker: Senator from Oregon and a close friend of President Lincoln, who died at the Battle of Ball’s Bluff. His death helped spur the creation of the committee.

- William Pitt Fessenden: Senator from Maine who spoke for the need for public inquiry into military defeats.

- John C. Frémont: Union General, commander of the Western Department and favored by the Committee. The committee leaked his written statement to the press in order to garner public support for him.

- William R. Montgomery: Union General investigated by the committee based on newspaper accounts of his actions.

- George McClellan: Union Major General relieved of command of the Army of the Potomac in November 1862. The Committee recommended his removal.

- Charles Pomeroy Stone: Union Brigadier General arrested and imprisoned on the Committee’s recommendation.

- W.T. Sherman: Union Major General who provided reports to the Committee in 1866.

- George H. Thomas: Union Major General who provided reports to the Committee in 1866.

- John Pope: Union Major General who provided reports to the Committee in 1866.

- J.S. Foster: Union Major General who provided reports to the Committee in 1866.

- A. Pleasanton: Union Major General who provided reports to the Committee in 1866.

- E.A. Hitchcock: Union Major General who provided reports to the Committee in 1866.

- P.H. Sheridan: Union Major General who provided reports to the Committee in 1866.

- James B. Ricketts: Union Brigadier General who provided reports to the Committee in 1866.

- Nathan Bedford Forrest: Confederate Major General whose troops were responsible for the massacre of Union black troops at Fort Pillow.

- Henry Wilson: Senator from Massachusetts who was present at Bull Run. His buggy was destroyed by a Confederate shell.

- James Grimes: Senator from Iowa who was present at Bull Run and barely avoided capture.

- Benjamin Perley Poore: Journalist who witnessed the Battle of Bull Run and later criticized the Joint Committee for assuming dictatorial powers.

Civil War: Documentation from the United States Congress Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War

The reports from the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War span 5,560 pages across ten volumes.

Established on December 9, 1861, after the Union’s defeat at the Battle of Ball’s Bluff, the Joint Committee, also known as the War Committee, was initiated by Senator Zachariah T. Chandler of Michigan. It concluded its activities in May 1865.

The Committee looked into matters such as illegal trade with Confederate states, medical care for injured soldiers, military contracts, and reasons behind Union military losses. The majority of its members supported emancipation, the enlistment of black soldiers, and the appointment of generals noted for their aggressive combat style. Senator Benjamin Wade of Ohio chaired the Committee throughout its duration and it became associated with the Radical Republicans who advocated for more assertive war strategies compared to those proposed by Abraham Lincoln.

The Committee generated numerous volumes that compiled extensive reports derived from fieldwork and testimonies from multiple witnesses. Eight volumes were released at various times during the four years of the committee’s operation.

Over its course, the committee convened 272 times and gathered testimonies in Washington and other venues, frequently from military personnel. Although the hearings were conducted in secrecy, the testimony and accompanying materials were published sporadically. Two Supplemental volumes released in 1866 contain original manuscripts of specific postwar reports received from the army.

This collection features:

Report of the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War at the second session Thirty-eighth Congress (1863) Part 1

Report of the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War at the second session Thirty-eighth Congress (1863) Part 2 Report of the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War during the second session of the Thirty-eighth Congress (1863) Part 3

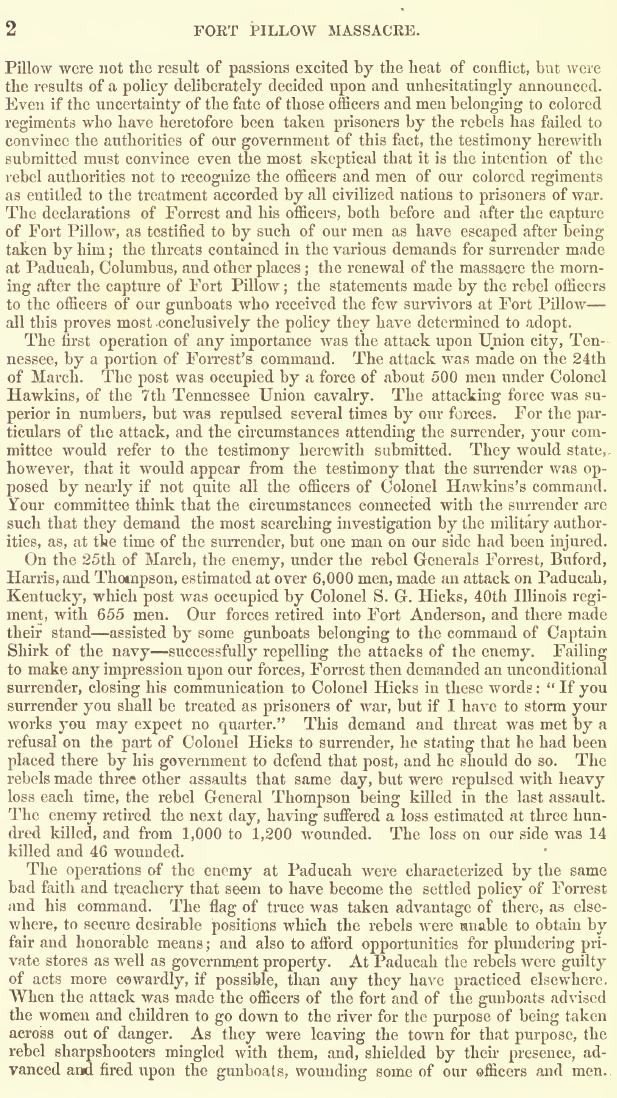

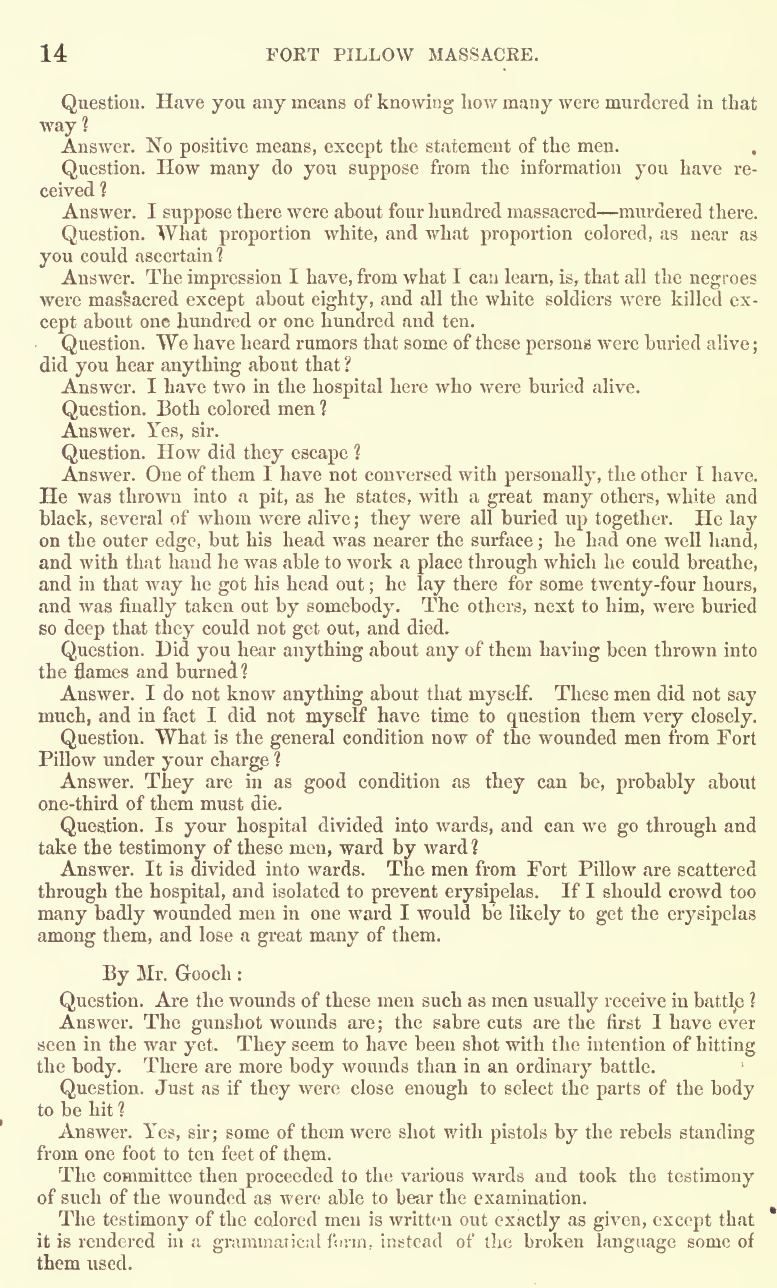

Fort Pillow Massacre (1864)

Returned Prisoners (1864)

Report of the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War during the second session of the Thirty-eighth Congress (1865) Volume 1

Report of the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War during the second session of the Thirty-eighth Congress (1865) Volume 2

Report of the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War during the second session of the Thirty-eighth Congress (1865) Volume 3

Supplemental report of the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War, in two volumes (1866) Volume 1

Supplemental report of the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War, in two volumes (1866) Volume 2

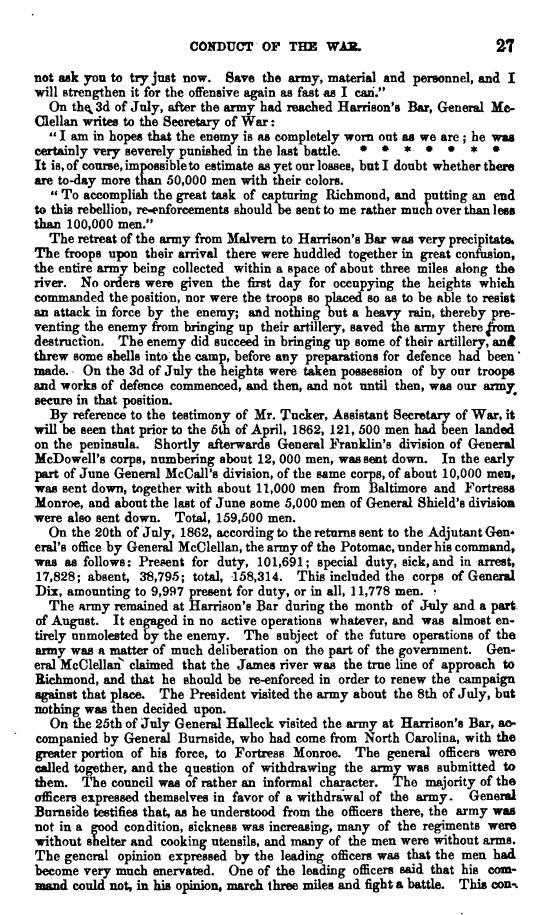

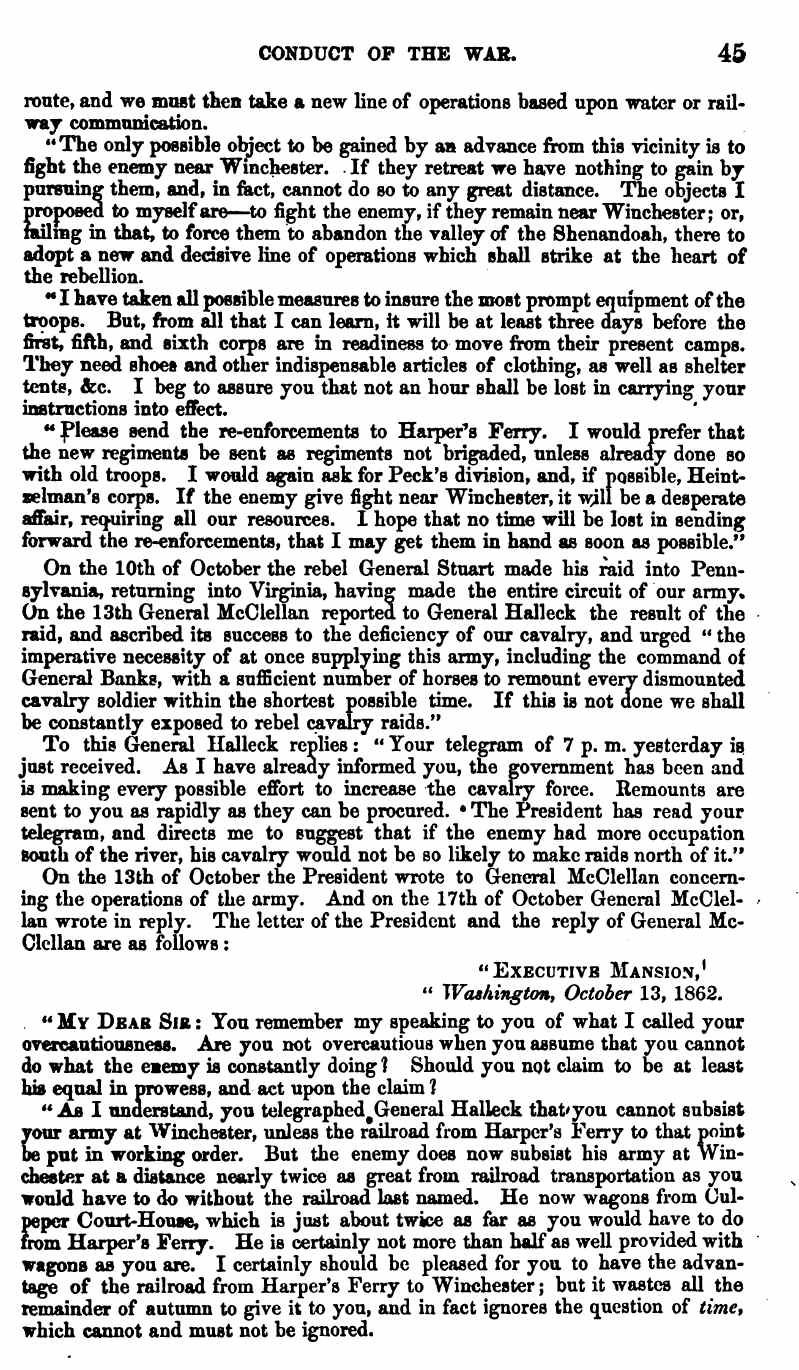

The committee’s initial report was published in 1863 and consisted of three sections. The first section focused on the Army of the Potomac. The second section addressed the Union’s losses in the Eastern Theater during 1861, specifically at First Bull Run and Ball’s Bluff. The third section examined events in the Western Theater of the war.

The committee’s subsequent report was released in two parts in 1864. The first part detailed accounts and testimonies regarding the alleged mistreatment of United States Colored Troops by Confederate forces after their surrender at Fort Pillow. This battle culminated in a massacre of surrendered Federal black soldiers by troops led by Confederate Major General Nathan Bedford Forrest. The second part discussed the circumstances surrounding Union soldiers who were returned after being held in Confederate POW camps. The third report published in 1865 was more detailed than the reports from the previous two years. It was divided into three sections that addressed various topics: the Mine Crater event during the Siege of Petersburg, the Fort Pillow incident, military campaigns at Fort Fisher, and operations along the Red River. Significant testimonies were gathered regarding ordnance, contracts for ice supply for wartime use, turreted Monitor-class naval vessels, and the massacre of friendly Cheyenne Indians at Sand Creek, Colorado. The report also includes the committee’s journal covering the period from January 20, 1864, to May 22, 1865.

In 1866, a supplementary two-volume set was released that included reports submitted to the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War by several Major Generals, including W. T. Sherman, George H. Thomas, John Pope, J. S. Foster, A. Pleasanton, E. A. Hitchcock, P. H. Sheridan, and Brigadier General James B. Ricketts.

Each page has been graphically reproduced on the disc. A text transcription of all text that can be recognized by computers is incorporated into the graphic representation of each page of every document, allowing for a searchable resource. Text searches can be conducted across all files contained on the disc.

About the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War

Resolution adopted: Senate, December 9, 1861; House, December 10, 1861 Final report issued: May 22, 1865 Chairman: Senator Benjamin Wade (R-OH)

Committee members: Zachariah Chandler (Senate, R-MI) John Covode (House, R-PA); succeeded by Benjamin Loan (R-MO) Daniel Gooch (House, R-MA) Andrew Johnson (Senate, D-TN); succeeded by Joseph Wright (Unionist-IN); succeeded by Benjamin Harding (D-OR) George Julian (House, R-IN) Moses Odell (House, D-NY)

Origins of the Committee On July 21, 1861, a number of Congress members traveled from Washington, D.C., to Centreville, Virginia, to observe the Union Army in battle. Positioned on a hill overlooking Bull Run Creek, lawmakers, together with journalists and interested civilians, enjoyed picnic lunches while watching the conflict, which became known as the “Picnic Battle.” Journalist Benjamin Perley Poore noted that spectators came out “as if they were attending a horse race or a Fourth of July celebration.” The Union Army performed admirably in the morning, but by early afternoon, the Confederates, bolstered by reinforcements, shifted the momentum. When Union generals ordered a retreat around 4:00 p.m., panicked soldiers rushed away, unintentionally pulling civilians along in their flight back to Washington.

Close to the battlefield, a group of senators heard a commotion and turned to see the road congested with fleeing soldiers, horses, and wagons. “Turn back, turn back, we’re defeated,” shouted Union troops as they dashed past the onlookers. Alarmed, Michigan senator Zachariah Chandler attempted to block the path to halt the retreat. Senator Benjamin Wade from Ohio, recognizing the disgrace of defeat, picked up an abandoned rifle and threatened to shoot any soldier who fled. Meanwhile, Senator Henry Wilson from Massachusetts handed out sandwiches until a Confederate shell hit his buggy, forcing him to escape on a stray mule. Iowa senator James Grimes narrowly avoided capture and vowed never to approach another battlefield.

Disheartened, the senators returned to Washington to report their firsthand experiences to a shocked President Lincoln. The loss at Bull Run disappointed many in the North and marked the beginning of several Union military setbacks. Casualties increased, and in October, Senator Edward D. Baker from Oregon, who was a close ally of President Lincoln, was killed during the Battle of Ball’s Bluff. During the early sessions of the 37th Congress (1861-1863), both the public and lawmakers urged for an investigation into the alarming defeats faced by the Union Army. Senator William Pitt Fessenden from Maine expressed the sentiments of many when he remarked, “We witness many actions that fail to gain public approval. There are certain actions we personally disapprove of that clearly require an investigation or, at the very least, an explanation that would satisfy the populace.” (The Congressional Globe, 37th Cong., 2d sess., 9 Dec, 1861, 30.)

In light of this, Senator Chandler proposed a resolution on December 5, 1861, to look into the battles of Bull Run and Ball’s Bluff, while other senators called for a comprehensive inquiry regarding the war’s management. As a result, Senator Grimes modified the resolution to request a joint committee to review all aspects of the war. The concurrent resolution, which was approved on December 10, 1861, established a joint committee made up of three senators and four representatives, giving its members the authority to “investigate the conduct of the current war and summon individuals and documents.” (The Congressional Globe, 37th Cong., 2d sess., December 5, 9, 10, 1861, 16, 32, 40; Bruce Tap, Over Lincoln’s Shoulder: The Committee on the Conduct of the War, (Lawrence: The University of Kansas Press, 1998), 24.) The committee included five Republicans and two Democrats, highlighting the dominance of Republicans in Congress during the Civil War period. Normally, the senator who introduced the resolution would lead the committee, but Chandler chose to let his close associate Senator Wade take the role, as he felt Wade’s legal expertise made him particularly qualified to oversee the investigation.

The members of the joint committee decided to keep their discussions confidential. They convened in a Senate committee room, did not hold any public hearings, and prohibited witnesses from talking to the media.

Despite agreeing to these rules, the committee members frequently leaked information to newspapers to build public support for their initiatives. For instance, in March 1862, they shared General John C. Frémont’s written statement with the New York Daily Tribune, aiming to rally public opinion behind his contentious actions and encourage Lincoln to reappoint him.

The investigations conducted by the committee were partially influenced by claims in popular newspapers regarding the performance of military leaders and conditions on the battlefield. In response to reports that General William R. Montgomery was treating soldiers poorly while being overly lenient towards disloyal individuals, the Joint Committee summoned Montgomery to testify regarding these allegations. Abolitionists referred to as “Radical Republicans” were in control of the committee and often criticized the president’s military strategy for not being sufficiently aggressive. Senator Wade, frustrated with Lincoln’s slow progress on emancipation and civil rights for African Americans, labeled him “a fool.” (Benjamin Wade to Caroline Wade, 25 Oct 1861, Benjamin F. Wade Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress)

The joint committee encountered criticism from Washington insiders who claimed its efforts were misguided and poorly informed. Detractors pointed out that while the committee had good intentions, its members lacked military experience and appeared unqualified to evaluate war decisions and the leaders responsible for them. Some military officials disregarded the investigation as partisan or ideological, arguing it was not in the nation’s best interest. Benjamin Perley Poore condemned the committee as “a mischievous organization, which assumed dictatorial powers.” (Poore, Perley’s Reminiscences of Sixty Years in the National Metropolis, 103-104.)

Despite this criticism, the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War maintained an extensive investigative agenda. Besides reviewing unsuccessful military campaigns, the committee examined a variety of significant issues such as corruption in military supply contracts, harsh treatment of Union prisoners by Confederate troops, the massacre of Cheyenne Indians, commercial activities by the Union, and gunboat construction, among others. The joint committee operated through two Congresses, convening 272 times over four years. Subcommittees were established to optimize time and resources and to meet with as many witnesses as possible. (Doyle, “The Conduct of the War, 1861,” 1201; Chicago Tribune 11 Apr 1862, 2.) Committee members often traveled outside Washington, D.C., gathering witness testimonies and directly evaluating the war effort. One investigation involved visiting a local army rehabilitation center in Alexandria, Virginia, to observe how medical teams treated Union soldiers.

Although Senator Wade harshly criticized Lincoln, the joint committee maintained positive relations with the executive branch. President Lincoln, along with his successor Andrew Johnson (who had been part of the joint committee), and their administrations cooperated with the committee’s requests for meetings and information access. The committee members frequently held military leaders accountable for Union defeats, often accusing them of being disloyal to the government, and they advocated for changes in military leadership. They urged Lincoln to dismiss Major General George McClellan from command of the Army of the Potomac following repeated early losses in the war. Ultimately, Lincoln removed McClellan in November 1862, but he did so on his own terms, largely ignoring the committee’s suggestions.

In a different instance, however, the committee was more persuasive, and the president agreed to their demand for the arrest and imprisonment of Brigadier General Charles Pomeroy Stone, as they had long questioned his loyalty and held him responsible for Union setbacks. The Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War generated extensive reports stemming from their field research and numerous witness testimonies. These reports were released at intervals during the committee’s four-year period and were frequently summarized by newspapers. However, compared to other congressional inquiries, the efforts of the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War largely went unnoticed by the American public. Despite this lack of visibility, the committee effectively carried out Congress’s oversight role during a national crisis. Members of the committee believed that their investigations encouraged President Lincoln to reassess his strategy and the effectiveness of his leading military commanders. Conversations with military leaders yielded in-depth descriptions of battlefield actions and created an important record of wartime occurrences that might have otherwise been lost.

Related products

-

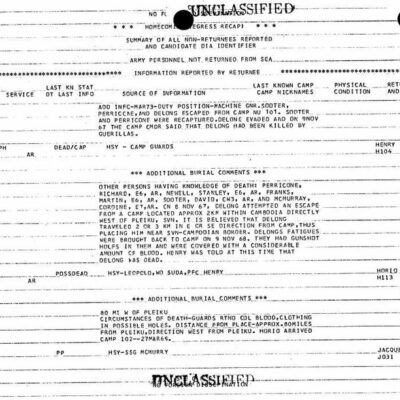

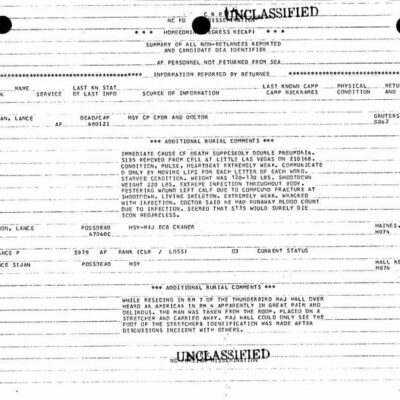

Vietnam War: POW/MIA Summary of All Reported Non-Returnees

$19.50 Add to Cart -

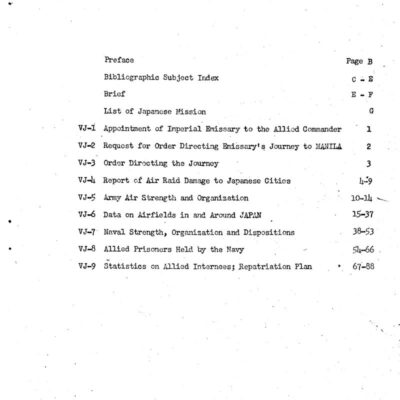

Japan’s Surrender Documents from World War II

$1.99 Add to Cart -

World War II: Felix Hall Lynching – FBI Files, Articles, Historical Records

$9.99 Add to Cart -

World War II: Targeted Aerial Objectives for Retaliatory Gas Attacks on Germany and Japan

$3.94 Add to Cart