Cambridge Five Spy Ring – Kim Philby Spy Case

$19.50

Description

Cambridge Five: A Timeline of Soviet Espionage

Timeline of the Cambridge Five Spy Ring

1930s:

- Early 1930s: Kim Philby, Guy Burgess, Donald McLean, Anthony Blunt, and John Cairncross are students at the University of Cambridge. They are all recruited as Soviet spies due to their communist sympathies.

- Mid-1930s: Soviet intelligence shifts recruitment strategy to target bright, young communists at leading universities, instructing them to break ties with other communists and infiltrate positions of power. Arnold Deutsch plays a key role in this recruitment, notably of Philby.

- 1936: John Cairncross is recruited by James Klugmann to become a Soviet spy.

Late 1930s – World War II (1939-1945):

- 1937: Guy Burgess and Donald McLean join the British Foreign Office.

- 1938: John Cairncross works at the British Treasury.

- Early World War II: Kim Philby enters the British Secret Intelligence Service (MI6).

- During World War II: Burgess and McLean supply Moscow with significant secrets from the Foreign Office, including information related to NATO’s formation and highly classified nuclear information.

- During World War II: Philby works within MI6.

- During World War II: Anthony Blunt provides a “phenomenal amount of intelligence” to Moscow and runs a sub-agent, Leo Long, in British military intelligence.

- 1942: John Cairncross transfers to MI6.

- 1943: Soviet intelligence briefly suspects Blunt and the Cambridge Five of being part of a Double Cross System against the USSR.

- 1944: John Cairncross joins MI6’s counter-intelligence section under Kim Philby. He produces an order of battle of the SS.

- March 1945: Leak of Foreign Office telegrams from the British Embassy in Washington D.C. to the Russians.

Post-World War II (1945-1950):

- Late 1940s: Burgess and McLean deliver a flow of information on Western policy to Moscow, including intentions regarding the Marshall Plan.

- Post-World War II: Philby becomes head of counterespionage operations within MI6.

- 1949: Kim Philby becomes the top British intelligence officer in Washington D.C.

The Unraveling (1951-1964):

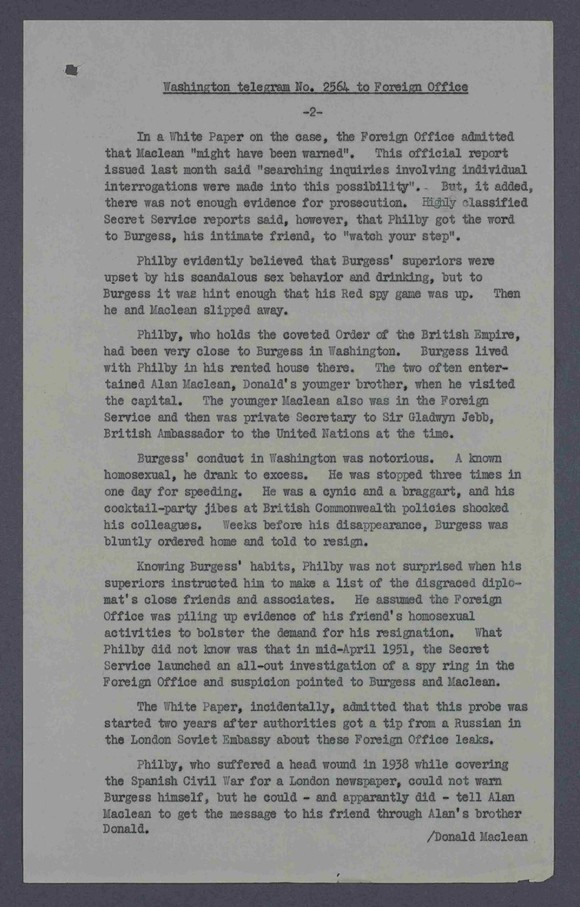

- 1951: Allied counterintelligence begins to suspect Donald McLean is a mole. Philby learns of this and warns McLean through Burgess.

- May 1951: Guy Burgess and Donald McLean disappear from London and later surface in Moscow (confirmed in 1956). The FBI begins an espionage investigation.

- 1951: Suspicion falls on Philby due to his close association with Burgess and McLean. He is relieved of his intelligence duties.

- 1955: Kim Philby is dismissed from MI6.

- 1959: MI5, unaware of Blunt’s involvement, encourages him to write to Burgess in Moscow to dissuade him from returning to the UK.

- January 11, 1963: MI6 officer Nicholas Elliott confronts Kim Philby in Beirut. Philby confesses to being a Soviet agent but then flees to the Soviet Union.

- 1963: British Cabinet Office files document the government’s response to Philby’s disappearance, focusing on media management and fallout.

- 1964: MI5 receives information from Michael Whitney Straight implicating Anthony Blunt in espionage.

- 1964: Anthony Blunt is interrogated by MI5 and confesses in exchange for immunity from prosecution. During his confession, he accuses John Cairncross of being part of the spy ring.

- February 1964: British Cabinet Office files cover the political reaction to John Cairncross’s confession, discussing potential prosecution and the US government’s involvement.

- 1964: John Cairncross confesses to spying.

- 1965: The FBI produces a report summarizing their findings on the Cambridge spies, including chronologies and information about their backgrounds and activities.

Public Exposure and Aftermath (1979-1995):

- 1979: Anthony Blunt is publicly accused of being a Soviet agent by investigative journalist Andrew Boyle.

- November 1979: Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher admits to the House of Commons that Anthony Blunt had confessed to being a Soviet spy in 1964.

- 1979-1992: Prime Minister’s Office papers cover the security of the Secret Service concerning Anthony Blunt, including the custody of his papers.

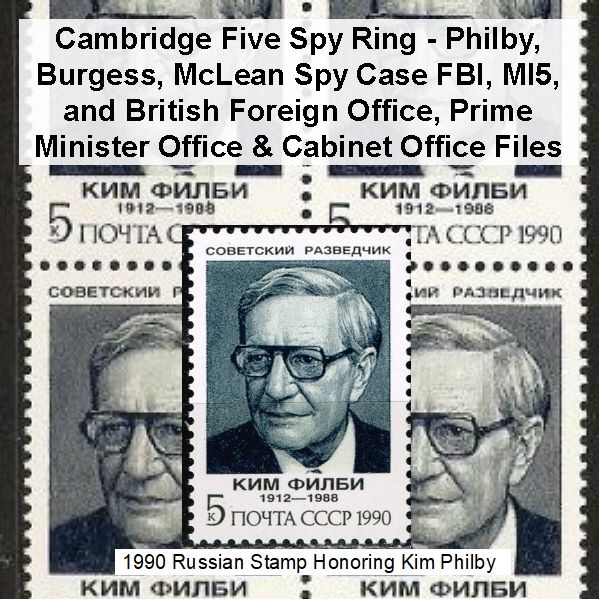

- 1988: Kim Philby dies in Moscow and is buried with full honors.

- 1990: John Cairncross is publicly accused of being the “fifth man.”

- 1995: John Cairncross dies.

- September 2019: Some MI5 files related to the Cambridge Five become available to the public.

Cast of Characters

- Kim Philby (Harold Adrian Russell ‘Kim’ Philby): A member of the Cambridge Five spy ring. He joined MI6 and rose to become head of counterespionage operations after WWII and the top British intelligence officer in Washington D.C. in 1949. He warned Burgess and McLean of impending arrest and eventually fled to the Soviet Union in 1963. He confessed to MI6 officer Nicholas Elliott before defecting.

- Guy Burgess: A member of the Cambridge Five spy ring. He was a British diplomat in the Foreign Office. He disappeared with Donald McLean in 1951 and resurfaced in Moscow in 1956. His “louche” lifestyle was known, but the extent of his personal life and espionage activities were not fully understood until his defection.

- Donald McLean: A member of the Cambridge Five spy ring. He was a British diplomat in the Foreign Office. He disappeared with Guy Burgess in 1951 and resurfaced in Moscow in 1956. He supplied significant secrets, including nuclear information, to the Soviet Union. He was identified as the Soviet source codenamed “Homer.”

- Anthony Blunt: A member of the Cambridge Five spy ring. He was a former curator for the art collection of Queen Elizabeth II and also worked for MI5. He provided a large amount of intelligence to Moscow and ran a sub-agent. He confessed to British intelligence in 1964 in exchange for immunity and publicly acknowledged as a spy in 1979.

- John Cairncross: A member of the Cambridge Five spy ring. He was a British literary scholar who worked at the British Treasury, the Cabinet Office (as private secretary to Sir Maurice Hankey), and later MI6. He confessed to spying in 1964 and was publicly identified as the “fifth man” in 1990.

- Arnold Deutsch: An Austrian of Czech origin and a Soviet ‘illegal’ who came to Britain in 1934. He was the key Soviet agent responsible for recruiting the Cambridge Five, particularly Kim Philby, using a strategy focused on bright university students.

- Nicholas Elliott: A close friend of Kim Philby and an MI6 intelligence officer. He confronted Philby in Beirut in 1963, leading to Philby’s confession before his defection to the Soviet Union.

- Michael Whitney Straight: An American author who knew Anthony Blunt at Cambridge. He informed MI5 in 1964 that Blunt had tried to recruit him as a spy in the 1930s, leading to Blunt’s confession.

- Roger Hollis: A future Director General of MI5 who was one of the few people in wartime MI5 to suspect Anthony Blunt.

- Peter Wright: An MI5 officer who, along with Arthur Martin, interrogated Anthony Blunt in 1964.

- Arthur Martin: An MI5 officer who, along with Peter Wright, interrogated Anthony Blunt in 1964.

- Andrew Boyle: An investigative journalist who publicly accused Anthony Blunt of being a Soviet agent in his 1979 book “Climate of Treason.”

- Margaret Thatcher: The British Prime Minister who admitted to the House of Commons in November 1979 that Anthony Blunt had confessed to being a Soviet spy in 1964.

- James Klugmann: A recruiter who enlisted John Cairncross as a Soviet spy in 1936.

- Sir Maurice Hankey: A prominent British civil servant for whom John Cairncross served as a private secretary in the Cabinet Office.

- Helenus Milmo: A barrister brought in to question Kim Philby. His report concluded that Philby was likely a Soviet agent, but this was not initially accepted by MI6 leadership.

- Sir John Sinclair: The head of MI6 who dismissed Helenus Milmo’s report on Philby due to a lack of “positive evidence.”

- General Walter Bedell Smith: An American general informed of the disappearance of Burgess and McLean.

- Air Marshal William Elliot: A British Air Marshal informed of the disappearance of Burgess and McLean.

- Leo Long: A sub-agent run by Anthony Blunt within British military intelligence.

- Harold Nicolson: A diplomat, politician, and author whose intercepted correspondence with Guy Burgess after his defection was of interest to MI5.

- Clarissa Churchill: The niece of Winston Churchill who had an affair with Guy Burgess. She later married Anthony Eden.

- Maynard Keynes, Victor Rothschild, EM Forster, WH Auden, Stephen Spender, Somerset Maugham: Individuals within Guy Burgess’s social circles, highlighting the diverse and influential network he operated within.

Cambridge Five Spy Ring – Kim Philby Spy Case FBI, MI5, and British Foreign & Prime Minister Office

8,236 pages of Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and British MI5, Security Service, Foreign Office, Prime Minister’s Office & Cabinet Office files covering The Cambridge Five Spy Ring. Some of the MI5 files where not available to the public until September 2019.

The Cambridge Five members (Kim Philby, Guy Burgess, Donald McLean, Anthony Blunt and John Cairncross) are perhaps the most infamous spy ring of the 20th century. They worked their way into the upper ranks of British Intelligence in order to spy for the Soviet Union. Their work is considered to have contributed to the deaths of dozens of British agents. None of the Cambridge Five were ever prosecuted. The term “Cambridge” for the group is used because they all were students at the University of Cambridge in the 1930s.

Guy Burgess and Donald McLean were British diplomats who disappeared in 1951 and surfaced in Moscow in 1956. There was speculation that Harold “Kim” Philby, head of the Soviet section of the British Secret Intelligence Service, was the “third man” who alerted them before they could be arrested for espionage. At one time the spy ring was called the Cambridge Three.

Burgess and McLean joined the British Foreign Office, from which they supplied secrets, including highly classified nuclear information and secrets relating to the formation of NATO. Philby entered the British Secret Intelligence Service (MI-6), becoming head of counterespionage operations after World War II and the top British intelligence officer in Washington D.C. in 1949. Burgess and McLean delivered a flow of information on Western policy to Moscow in the 1940s, including the West’s intentions on the Marshall Plan. McLean and Philby betrayed agents infiltrating the Balkans, who were apprehended and shot.

Anthony Blunt provided a phenomenal amount of intelligence to Moscow as well as running a sub-agent, Leo Long, in British military intelligence. To Soviet intelligence it increasingly seemed too good to be true. In 1943, it concluded that Blunt and the rest of the Cambridge Five must be part of a Double Cross System directed against the Soviet Union. Not until a few months before D-Day did they finally accept that the intelligence provided by the Five was genuine.

In 1951, Allied counterintelligence began to suspect McLean was a mole. Philby got wind of this and warned McLean, through Burgess. Both Burgess and McLean immediately fled to Moscow. Philby had saved his friends, but his close association with them brought suspicion upon himself. In 1951 he was relieved of his intelligence duties; in 1955 he was dismissed from MI-6. With counterintelligence closing in on him, he fled to the Soviet Union in 1963. When Kim Philby died in 1988, he was buried with full honors in a Moscow cemetery.

Two others Anthony Blunt and John Cairncross confessed to British intelligence, but this remained a secret for many years. Blunt’s involvement in the ring was not public until 1979 and 1990 for Cairncross. From then on, they were known as the Cambridge Five.

Anthony Blunt was a former curator for the art collection of Queen Elizabeth II. He also worked for the MI5. In 1964, MI5 received information from the American author Michael Whitney Straight pointing to Blunt’s espionage. Straight and Blunt knew each other at Cambridge in the 1930’s. He said that Blunt tried to recruit him as a spy, he first agreed, but later changed his mind. Blunt was interrogated by MI5 and confessed in exchange for immunity from prosecution. Blunt during his confession accused John Cairncross of being a part of the spy ring.

Probably the only person in the wartime MI5 Security Service who became suspicious of Blunt was the future Director General Roger Hollis. When, almost twenty years later, Blunt confessed to having been a Soviet agent, he told his interrogators, Peter Wright and Arthur Martin, ‘I believe [Hollis] disliked me – I believe he slightly suspected me.’

By 1979, Blunt was publicly accused of being a Soviet agent by investigative journalist Andrew Boyle, in his book Climate of Treason. In November 1979, Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher admitted to the House of Commons that Blunt had confessed to being a Soviet spy fifteen years previously.

John Cairncross (1913–1995) was a well-known British literary scholar. He was recruited in 1936 by James Klugmann to become a Soviet spy. In 1938, he worked at the British Treasury and later for the British Cabinet Office where he served as the private secretary of Sir Maurice Hankey. Four years later, he was transferred to the MI6. Cairncross confessed to spying in 1964 and was publicly accused of being the “fifth man” in 1990.

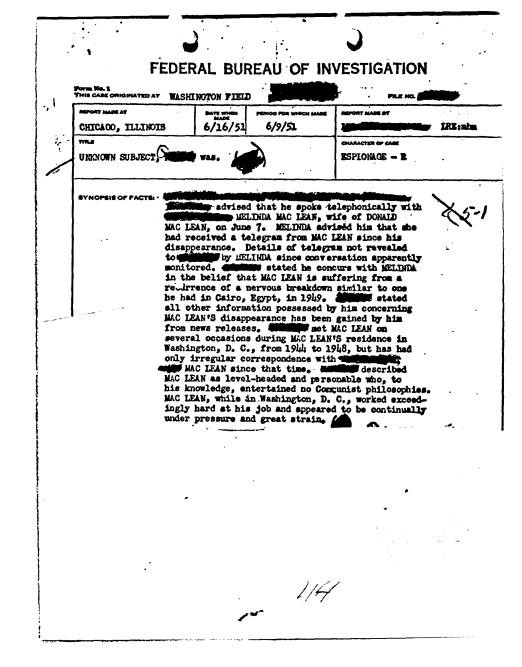

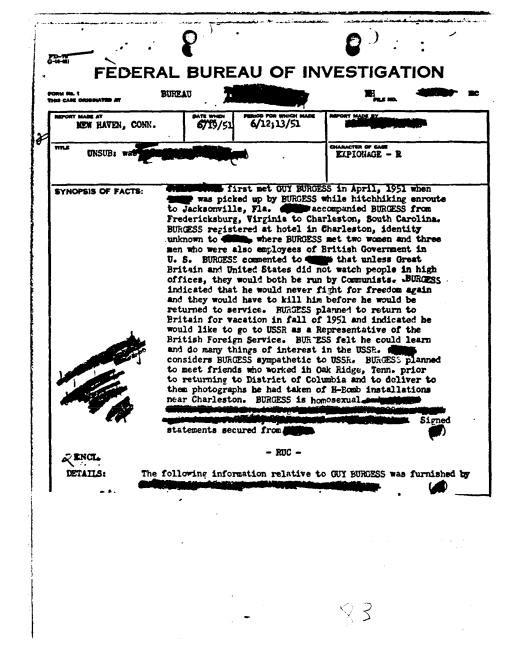

FBI FILES

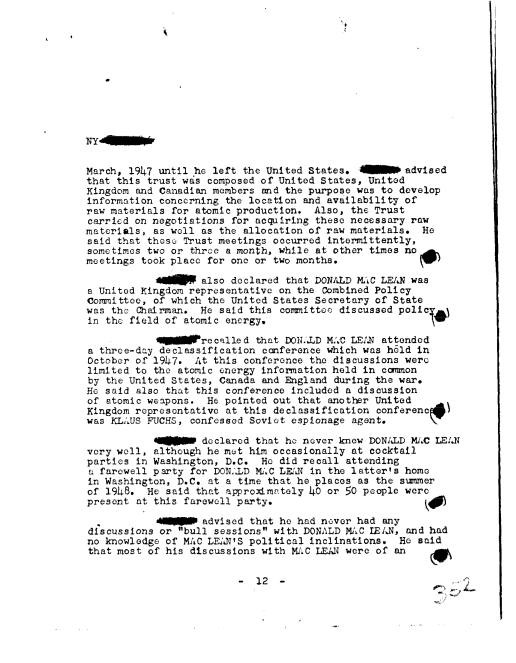

3,316 pages of FBI files mostly covering Kim Philby, Guy Burgess, and Donald MacLean. The files date from 1951 to 1973. Beginning in 1951 the FBI began an espionage investigation when the disappearance of Burgess and MacLean became known. Material includes synopses of facts and results of interviews of many of who had contact with the spies. In 1965, the Bureau produced a report summarizing their findings. The report contains a chronology of events, summaries of communications from Burgess and McLean, and information about the spies’ backgrounds, political beliefs, and associates.

British Cabinet Office Files

192 pages dating from January 1963 to December 1963, covering the disappearance of Harold Adrian Russell ‘Kim’ Philby, former member of the Foreign Service. This file documents the response of the British government to the disappearance of Kim Philby from Beirut, with particular reference to the approach to be taken with the media, and the likely fall out from the events.

Other pages cover John Cairncross, former member of the Foreign Service, and his confession to spying. Other material covers the political reaction to John Cairncross’ confession in February 1964. It contains details of the high-level discussions which took place regarding how the government should react, whether or not it would be possible to bring Cairncross to trial, and whether the US government should be pressed to deport him. Between 1941 and 1945, Cairncross supplied the Soviets with 5,832 documents, according to the Russian archives. In 1944, Cairncross joined MI6, the foreign intelligence service. In Section V, the counter-intelligence section, Cairncross produced under the direction of Kim Philby an order of battle of the SS. Cairncross later suggested that he was unaware of Philby’s connections with the Russians. MI5 had previously found papers in Guy Burgess’s flat with a handwritten note from him, after Burgess’s flight to Moscow.

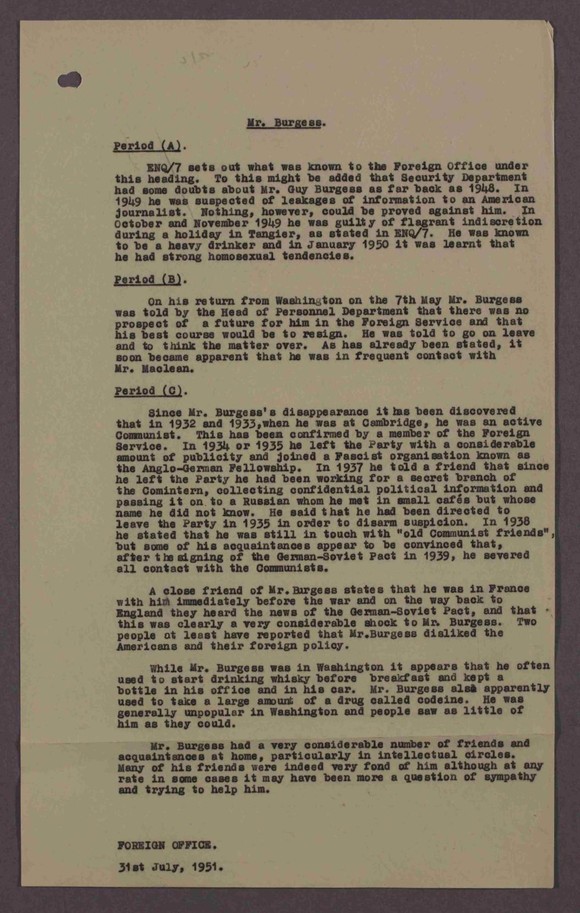

Includes the Report of Cadogan Committee of Enquiry and Consequences of the Burgess and McLean Affair. The report discloses that Foreign Office and Security Service officials were only made aware of concerns about the pair after they had defected to Russia. The inquiry states that although some of his colleagues were aware of Burgess’ “louche” lifestyle, the Foreign Office did not know about the details concerning his personal life until he disappeared.

British Foreign Office And Foreign And Commonwealth Office Files

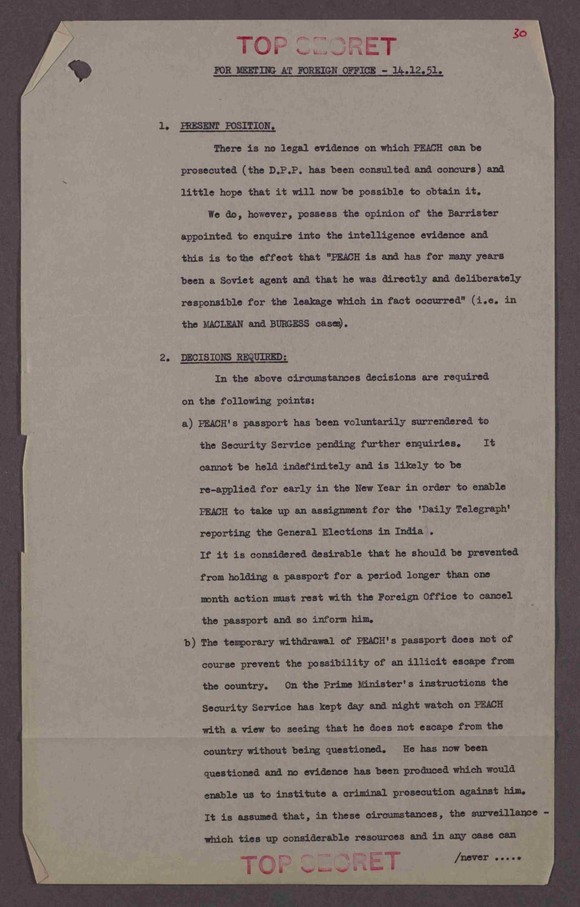

1,841 pages dating from January 1949 to December 1953, records relating to Philby, Guy Burgess and Donald McLean (known KGB spies), and subsequent investigations and security arrangements. The MI5’s code name for Kim Philby was “Peach.” Files cover the investigation into the leak of Foreign Office telegrams from the British Embassy, Washington, DC, to the Russians, in March 1945. Records relating to Guy Burgess and Donald McLean (known KGB spies), and subsequent investigations and security arrangements.

Files cover: Disappearance of Guy Burgess and Donald McLean, informing General Walter Bedell Smith and Air Marshal William Elliot of the facts. Records relating to Guy Burgess and Donald McLean, and subsequent investigations and security arrangements. Documents related to the Cadogan Report on the disappearance of Guy Burgess and Donald McLean.

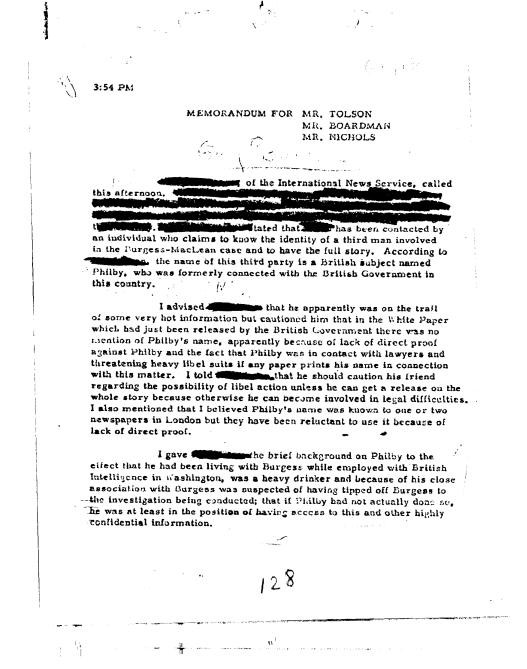

Includes a report written by a barrister, Helenus Milmo, who was brought into question Philby. His four hours of interrogating Philby lead to him writing a report in which he wrote “I find myself unable to avoid the conclusion that Philby is and has been for many years a Soviet agent.” However, Sir John Sinclair, head of MI6, concluded that Milmo’s report was, “based upon a mass of selected circumstantial material without a crumb of positive evidence.”

MI5 Files

2,537 of British Security Service MI5 files.

The MI5 was unaware that in the mid-1930s, Soviet intelligence had begun a new agent recruitment strategy, based on recruiting bright young Communists or Communist sympathizers from leading universities, who were told to break all links with other Communists and use their talents and educational success to penetrate the corridors of power. The most successful of ‘Stalin’s Englishmen’ were the ‘Cambridge Five’, described by the MI5 as, “possibly the ablest group of foreign agents ever recruited by Soviet intelligence.”

A major highlight in these files are extracts (File KV 4428) from a confession by Kim Philby.

On January 11, 1963, a former close friend of Philby, who was a MI6 intelligence officer Nicholas Elliott, confronted Philby in Beirut where Philby was working as a journalist. Philby confessed to Elliot. When Arnold Deutsch was recruiting him, Philby says he told him that, “a person with my family background and sensibilities could do far more for communism than the run-of-the-mill party member or sympathizer.” Philby said he supported the recruitment of MacLean but was not so certain about Burgess. According to Philby, “I was in favour of recruiting Donald, but entered strong reservations with regard to Guy, on the grounds of his unreliability and indiscretion.” Elliot offered him immunity from prosecution if he would return to London and confess, instead Philby boarded a Soviet ship headed back to Russia.

A file (KV 2/4103) on Guy Burgess contains papers dealing with Burgess’ background, including interviews with a number of his acquaintances, and intercepted correspondence to and from him after his defection to Moscow. Burgess disappeared from London in May 1951 with Donald McLean and later reappeared in Moscow. He was finally assessed as having been a Soviet agent because of Burgess’ handwritten letters from Moscow. Intercepted mail shows thing like a note to Burgess in Moscow from Royal National Lifeboat Institution saying: ‘We do not accept money from traitors’ and a letter from Burgess to his mother describing his life in the USSR .

Files show that MI5 learned that Burgess was considering coming back to England to see his sick mother. The MI5 thought this would be an embarrassment for Britain. There was uncertainty there was enough evidence to convict Burgess. So, they encouraged Anthony Blunt to write to Burgess in Moscow to discourage him from returning. A Foreign Office official wrote that, “We have taken steps to have the idea conveyed to Burgess that if he thinks he could come to this country with impunity he is gravely misinformed.” Unaware of Blunt’s spying, the letter he wrote to Burgess in 1959 at the behest of the MI5 said, “What the outcome of the trial would be is of course a matter of speculation, but on the way the whole story would be raked up again and many of your friends would certainly be called as witnesses, and mud slung in all directions.”

Files include coverage of Security Service Deputy Director General’s interview of Anthony Blunt and Tomas Harris after Burgess and McLean had disappeared. Intercepted correspondence between diplomat, politician and author Harold Nicolson (KV 2/4364) and Cambridge spy Guy Burgess who had fled to Moscow. Nicolson’s letters to Guy Burgess in the 1940s, left behind when the latter went to Moscow. Transcripts of wiretaps on Burgess’ mother’s phone.

A file on Arnold Deutsch. Deutsch was an Austrian of Czech origin, Deutsch came to Britain as a Soviet ‘illegal’ in 1934 and took the lead role in recruiting the ‘Cambridge Five’ group of Soviet spies, Philby in particular. His successful technique was based on the cultivation of radical university highfliers ahead of their employment in government. File includes the Security Service’s file for the investigation of a leakage in Washington which led to the unmasking of Donald McLean as a Soviet agent and his flight to Moscow with Guy Burgess. Soviet secret communications sent in 1944 that were intercepted and were deciphered in 1951. They indicated that the Soviets had a source in Washington D.C. with the code name “Homer.” The files include analysis that McLean as a ‘fit’ for “Homer”, the source of the leakage. Contains copies of the leaked telegrams, statements of Anthony Blunt and Goronwy Rees, and a brief for the Security Service’s Director General’s meeting with FBI director J. Edgar Hoover.

Information in the files reveal that Burgess had an affair with Clarissa Churchill, the niece of Winston Churchill, who later married Anthony Eden, who would serve as British Foreign Minister and Prime Minister. Other people in Burgess’ social circles included Maynard Keynes, Victor Rothschild, EM Forster, WH Auden, Stephen Spender and Somerset Maugham.

Prime Minister’s Office Papers

A 185-page file titled Security of the Secret Service: Professor Anthony Blunt. Material dated from 1979 to 1992. Includes paperwork about the custody of Anthony Blunt’s papers. Contains memos on Cairncross’ inquiry on whether or not he would be prosecuted if he returned to the United Kingdom.

,

NATIONAL SECURITY AGENCY

“The Venona Story,” An NSA monograph about the history of the program to decipher intercepted Soviet communications, which lead to the unveiling of the Cambridge Spy ring.