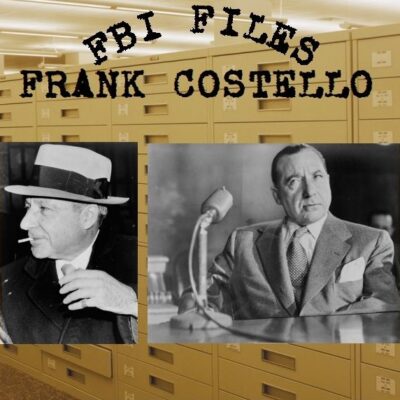

Bonnie & Clyde and the Barrow Gang FBI Files and Court Documents

$19.50

Description

Bonnie and Clyde: A Detailed Timeline and Biographies

Detailed Timeline of Events: Bonnie and Clyde and the Barrow Gang

January 1930: Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow meet in Dallas, Texas. Bonnie is 19 and married to an imprisoned burglar. A few days later, Clyde is arrested for burglary.

February 1930: Clyde escapes jail in Waco, Texas, with a gun smuggled to him by Bonnie.

March 1930: Clyde is recaptured and sent back to prison.

February 1932: Clyde is paroled from prison. He soon returns to a life of crime.

April 30, 1932: John Bucher, a storekeeper in Hillsboro, Texas, is fatally shot during a robbery believed to be committed by Clyde Barrow.

August 5, 1932: Undersheriff Eugene C. Moore is killed and Sheriff Charles Maxwell wounded in Atoka, Oklahoma, while investigating a disturbance where they encountered two suspicious men, believed to be Clyde Barrow and another accomplice.

October 11, 1932: Howard Hall, a butcher in Sherman, Texas, is killed while attempting to thwart a robbery by Clyde Barrow.

December 26, 1932: Doyle Johnson is shot and killed in Temple, Texas, while trying to stop the theft of his wife’s car.

January 6, 1933: Tarrant County Deputy Sheriff Malcolm Davis is killed in a gunfight with Barrow Gang members during a stakeout in West Dallas at the home of Raymond Hamilton’s sister.

April 13, 1933: Joplin, Missouri Shootout: Law enforcement officers approach a garage apartment hideout used by the Barrow Gang. Detective Harry McGinnis and Constable John Wes Harryman are killed in the ensuing gunfight. Bonnie and Clyde, along with Buck and Blanche Barrow and W.D. Jones, escape. The FBI later becomes involved in the case due to the interstate nature of their crimes, beginning with the investigation of stolen cars linked to the gang.

June 26, 1933: City Marshal Henry D. Humphrey is shot and killed at a roadblock north of Alma, Arkansas, while attempting to stop a car carrying Barrow Gang members.

July 20-27, 1933: A period of intense activity for the Barrow Gang, documented in a later FBI report summarizing leads and witness interviews.

July 29, 1933: Marvin “Buck” Barrow dies at Kings Daughters Hospital in Perry, Iowa, from gunshot wounds sustained during shootouts in Platte City, Missouri, and near Dexter, Iowa.

August 16, 1933: Blanche Barrow gives a five-page confession to authorities.

August 17, 1933: A 26-page FBI report details the Barrow Gang’s activities from July 20th to 27th, including Buck Barrow’s deathbed interview and a jailhouse interview with Blanche Barrow.

June 30, 1933: Sheriff George T. Corry of Collingsworth, Texas, is kidnapped by the Barrow Gang.

July 8, 1933: An eight-page FBI report details the kidnapping of Sheriff George T. Corry and Wellington, Texas, Chief of Police Paul Hardy by the Barrow Gang.

July 10, 1933: The brother of Constable J. W. Harryman, killed in Joplin, appears at the FBI Dallas office stating his intention to kill the Barrow brothers.

November 20, 1933: Sowers Ambush: Dallas County authorities attempt to ambush Bonnie and Clyde near Sowers, Texas, where they were expected to meet family. Sheriff “Smoot” Schmidt, Ted Hinton, Ed Caster, and Bob Alcorn open fire on their car. Bonnie and Clyde are wounded but manage to escape and steal another vehicle.

December 14, 1933: William Daniel Jones, a captured Barrow Gang member, provides information in an interview recounted in a memo.

December 23, 1933: An FBI report conveys information from Hattie Crawford, a nurse friend of Bonnie’s, who claims to have treated Clyde’s gunshot wounds.

January 5, 1934: An FBI report indicates Bonnie’s brother, Hubert “Buster” Parker, is willing to give up Clyde to save Bonnie.

January 16, 1934: Eastham State Farm Raid: The Barrow Gang raids the Texas State Prison system’s Eastham State Farm, freeing inmates Raymond Hamilton, Joe Palmer, Henry Methvin, and Hilton Bybee. Guard Major Crowson is killed and another guard wounded during the escape.

January 17, 1934: An FBI report is written at Eastham State Farm detailing information gained from interviews at the prison following the raid.

March 29, 1934: An FBI report provides details of the gang’s actions after the Eastham prison breakout, based on information from recaptured Hilton Bybee.

April 1, 1934: Grapevine Killings: Texas Highway Patrolmen E.B. Wheeler and H.D. Murphy are killed on Easter morning near Grapevine, Texas, after approaching a Barrow Gang car stopped on the side of the road.

April 6, 1934: Constable Calvin Campbell is shot and killed in Commerce, Oklahoma, while approaching a Barrow Gang car stuck in a muddy road. His partner is taken hostage.

April 21, 1934: An FBI memo notes information concerning Clyde Barrow’s attempts to contact a former girlfriend.

April 24, 1934: An FBI memo reveals that Bailey Tynes, Clyde Barrow’s cousin, is being paid as a bureau informant.

April 24, 1934: An FBI memo to J. Edgar Hoover details an immunity deal made by Texas authorities with the Methvin family in exchange for them “placing Barrow and Bonnie Parker on the spot.”

May 3, 1934: An FBI report contains a signed statement from captured James Mullen, giving an account of the Gang’s situation since the Eastham prison breakout.

May 3 – May 22, 1934: A series of memos, letters, and telegrams within the FBI indicate an intensifying and coordinated effort to locate and apprehend Bonnie and Clyde.

May 23, 1934: Ambush in Louisiana: A posse of law enforcement officers from Louisiana and Texas, including Frank Hamer, ambush Bonnie and Clyde near Sailes, Louisiana. They are killed instantly.

Cast of Characters and Brief Bios:

- Bonnie Parker: (1910-1934) A member of the Barrow Gang. Met Clyde Barrow in 1930. Involved in numerous robberies, kidnappings, and murders. Killed in the ambush in Louisiana.

- Clyde Barrow: (1909-1934) The leader of the Barrow Gang. Met Bonnie Parker in 1930. Responsible for numerous robberies, burglaries, kidnappings, and the deaths of multiple law enforcement officers and civilians. Killed in the ambush in Louisiana.

- Marvin “Buck” Barrow: (1903-1933) Clyde’s older brother and a member of the Barrow Gang. Participated in the Joplin shootout and was mortally wounded in subsequent encounters with law enforcement. Died in July 1933.

- Blanche Barrow: (1911-1988) Buck Barrow’s wife and a member of the Barrow Gang. Present during the Joplin shootout and other criminal activities. Captured in July 1933 and later confessed.

- William Daniel Jones: (1916-1974) A member of the Barrow Gang who joined in 1933. Was present during several robberies and encounters with law enforcement. Captured in late 1933.

- Raymond Hamilton: (1913-1935) An associate of Clyde Barrow who participated in earlier crimes and was later freed during the Eastham State Farm raid in January 1934. Was eventually recaptured and executed.

- Henry Methvin: (1912-1948) An inmate freed during the Eastham State Farm raid. His family allegedly made a deal with authorities to help set up Bonnie and Clyde in exchange for immunity for Henry.

- Joe Palmer: One of the inmates freed during the Eastham State Farm raid.

- Hilton Bybee: One of the inmates freed during the Eastham State Farm raid. Was later recaptured and provided information to the FBI.

- Frank Hamer: (1884-1955) A former Texas Ranger commissioned to track down and stop the Barrow Gang. Played a central role in the planning and execution of the ambush that killed Bonnie and Clyde.

- Lester Kindell: A Special Agent with the FBI’s New Orleans Division who played a key role in the cooperative effort between different law enforcement agencies to track the Barrow Gang in Louisiana and parts of Texas. He was involved in discussions leading to the final ambush but did not participate.

- George T. Corry: Sheriff of Collingsworth, Texas, who was kidnapped by the Barrow Gang in June 1933.

- Paul Hardy: Chief of Police of Wellington, Texas, who was kidnapped along with Sheriff Corry in July 1933.

- J. W. Harryman: Constable killed during the Joplin shootout in April 1933.

- “Smoot” Schmidt: Sheriff involved in the failed Sowers Ambush in November 1933.

- Ted Hinton: A Dallas County Deputy Sheriff involved in the Sowers Ambush.

- Ed Caster: A law enforcement officer involved in the Sowers Ambush.

- Bob Alcorn: A law enforcement officer involved in the Sowers Ambush.

- Hattie Crawford: A nurse friend of Bonnie Parker who reportedly treated Clyde’s gunshot wounds.

- Hubert “Buster” Parker: Bonnie Parker’s brother, who expressed a willingness to give up Clyde to save Bonnie.

- Major Crowson: A guard at Eastham State Farm who was killed during the Barrow Gang’s raid in January 1934.

- E.B. Wheeler: A Texas Highway Patrolman killed near Grapevine, Texas, on April 1, 1934.

- H.D. Murphy: A Texas Highway Patrolman and Wheeler’s partner, also killed near Grapevine on April 1, 1934.

- Calvin Campbell: A Constable in Commerce, Oklahoma, killed on April 6, 1934, believed to be the last person killed by the Barrow Gang.

- Bailey Tynes: Clyde Barrow’s cousin who was an informant for the FBI.

- Ivy Methvin: Henry Methvin’s father, who played a role in the ambush by positioning his truck to appear broken down.

- James Mullen: A captured member of the Barrow Gang who provided a statement about the gang’s activities after the Eastham breakout.

- Emma Parker: Bonnie Parker’s mother, who was interviewed for the book “Fugitives.”

- Nell Barrow Cowan: Clyde Barrow’s sister, who was also interviewed for the book “Fugitives.”

- Jan I. Fortune: The compiler, arranger, and editor of the book “Fugitives.”

- John Bucher: Storekeeper killed in Hillsboro, TX in April 1932.

- Eugene C. Moore: Undersheriff killed in Atoka, OK in August 1932.

- Howard Hall: Butcher killed in Sherman, TX in October 1932.

- Doyle Johnson: Man killed in Temple, TX in December 1932 while trying to prevent his car from being stolen.

- Malcolm Davis: Tarrant County Deputy Sheriff killed in Dallas, TX in January 1933.

- Harry McGinnis: Detective killed in Joplin, MO in April 1933.

- Henry D. Humphrey: City Marshal killed in Alma, AR in June 1933.

The Enduring Legend of Bonnie and Clyde in Grapevine, Texas

The story of Bonnie and Clyde in Grapevine, Texas is one woven into the fabric of American history. Their infamy as notorious outlaws during the Great Depression captivates the imagination and fuels an enduring fascination with their lives. Grapevine, a small town steeped in rich cultural history, holds a unique connection to this infamous duo. From their time spent in the town to local legends surrounding their escapades, Bonnie and Clyde’s narrative is not just a tale of crime but also an exploration of community dynamics during a tumultuous era in American society.

Grapevine’s Connection to Bonnie and Clyde: A Historical Overview

Understanding the significance of Bonnie and Clyde’s presence in Grapevine requires a dive into the historical context of their activities during the 1930s. Grapevine was a quaint community that found itself intersecting with the turbulent lives of these infamous criminals. The stories of their interactions with locals create a picture of a complex relationship between outlaws and the townsfolk who were both fascinated and terrified by their notoriety.

The Rise of Bonnie and Clyde Amidst Economic Turmoil

During the Great Depression, life was challenging for many Americans, and Grapevine was no exception. Farmers struggled, businesses faced closures, and desperation loomed large over communities. It was against this backdrop that Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow rose to notoriety.

Their criminal exploits were not only acts of rebellion against authority but also desperate measures to survive in a system that had failed many. Bonnie and Clyde became symbols of resistance against an oppressive economy.

While Grapevine played a peripheral role in their story, the environment of despair and hardship made them relatable to some locals, even as others saw them as dangerous criminals. This duality is part of what keeps their legend alive today.

Local Legends and Anecdotes

Grapevine is rich with tales about Bonnie and Clyde, many of which have been passed down through generations. One popular narrative describes how Clyde Barrow did not rob the Grapevine Home Bank because he had friends there. This speaks volumes about the nature of their connections in the area.

Locals share anecdotes about encounters with Bonnie and Clyde, including sightings at local hangouts or their brief stops in town. These stories often blend the lines between myth and reality, showcasing the way folklore can shape historical narratives.

The strong sense of community that Grapevine fosters has contributed to a desire to preserve these tales. Residents take pride in their town’s history, intertwining the legend of Bonnie and Clyde into the collective memory of Grapevine.

The Aftermath of Their Crimes: How Grapevine Responded

The criminal activities committed by Bonnie and Clyde and their gang had long-lasting impacts on Grapevine. The robbery of the Grapevine Home Bank in 1932 was one such event that sent shockwaves through the community.

Although Bonnie and Clyde themselves were not directly involved in this robbery, it marked the beginning of heightened law enforcement vigilance in the area. The violent nature of their crimes would eventually lead to their downfall, serving as a cautionary tale for other would-be criminals.

This response from the community illustrates how Bonnie and Clyde’s actions not only affected their own lives but also resonated throughout the towns they touched. Law enforcement became increasingly aggressive in their pursuit of outlaws, a trend echoed across Texas and beyond.

Bonnie and Clyde’s Friends and Allies in Grapevine

A key aspect of the Bonnie and Clyde saga in Grapevine is their network of friends and allies within the community. Understanding the relationships they had provides insight into the complexities of their existence outside the realm of crime.

The Role of Local Families

Many families in Grapevine had personal connections to Bonnie and Clyde, either through friendship or familial ties. As Mayor William D. Tate noted, both outlaws had friends and relatives in the area, suggesting that their influence was felt personally by many residents.

These friendships often blurred the lines between right and wrong, with locals torn between supporting their friends or condemning their actions. Such relationships reveal the human side of Bonnie and Clyde, challenging the black-and-white narratives often depicted in media portrayals.

The Impact of Community Connections

Community connections were significant for Bonnie and Clyde during their criminal career. They relied on local support systems for safe havens and assistance. The outlaws were adept at manipulation, often deceiving individuals who genuinely wanted to help.

One notable account involves Clyde Barrow tricking a farmer into providing him with a ride under false pretenses. This story underscores the complexities of trust and betrayal among people living in economically strained times.

The interplay between Bonnie and Clyde and Grapevine residents highlights the moral ambiguity present during the Great Depression. Many locals were sympathetic to the struggles faced by the outlaws, deepening the intrigue surrounding their legacy.

Lasting Friendships and Legacy

Despite the tragic end of their criminal enterprise, Bonnie and Clyde left behind lasting friendships in Grapevine. Their story became synonymous with the town’s identity, cementing their place in local lore.

Years later, reminiscences of those who knew them continue to propel interest in Bonnie and Clyde’s saga. Grapevine’s historical societies actively preserve these narratives, ensuring that the tales of friendship and defiance remain vibrant.

Ultimately, the enduring relationships forged in Grapevine remind us that even the darkest stories have elements of humanity, connection, and understanding that transcend societal judgment.

The Infamous Grapevine Bank Heist: A Detailed Examination

The Grapevine Home Bank robbery serves as a pivotal moment in the history of Bonnie and Clyde, albeit indirectly. This event, committed by members of Clyde’s gang, raises questions about the motivations behind such criminal acts and their lasting impact on the community.

The Robbery That Shook Grapevine

On December 31, 1932, two men associated with Bonnie and Clyde stormed the Grapevine Home Bank, capturing the attention of not only Grapevine residents but also the wider Texas community. As reported in the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, these men managed to deceive bank employees and customers, locking them in a vault while making off with $2,500.

The planning and execution of the robbery demonstrated a level of cunning that drew admiration and fear from locals. The audacity of such actions ultimately represented a challenge to law enforcement and a reminder of the shifting dynamics in society at the time.

The Pursuit and Capture of the Criminals

In the aftermath of the robbery, local citizens sprang into action. Gordon Tate, father of the current mayor, played a crucial role in the capture of one of the robbers. His decision to pursue the criminals armed with a rifle exemplified the spirit of community response during crises.

This narrative highlights how Grapevine residents took justice into their own hands during troubling times. Their courage and resourcefulness became emblematic of the era, illustrating a common theme in tales of resilience amid adversity.

The Consequences of the Heist

While Bonnie and Clyde were technically uninvolved in the Grapevine Home Bank robbery, the fallout from the incident still echoed through the community. Grapevine learned the harsh realities of crime firsthand, resulting in increased vigilance from law enforcement and a growing perception of danger.

As public sentiment shifted toward unrealized dread of crime, the bond between law enforcement and the community strengthened. Grapevine’s residents began to understand the importance of supporting police efforts to maintain order and safety.

The influence of this robbery on local consciousness is multifold, shaping the attitudes of future generations as they navigated their legacies intertwined with crime, justice, and community identity.

The Tragic Downfall of Bonnie and Clyde: An Intersection with Grapevine

Though Bonnie and Clyde’s reign of terror ended in tragedy, their demise marked a critical turning point in Grapevine’s history. The consequences of their violent criminal activities reverberated across Texas, amplifying the intensity of law enforcement responses.

The Final Showdown: Analyzing the Events Leading to Their Death

On May 23, 1934, Bonnie and Clyde were ambushed by law enforcement in Bienville Parish, Louisiana. Their deaths signaled the end of a chaotic era marked by robberies and murders. Interestingly, the increasing violence associated with their gang had, in part, roots in the events tied to Grapevine—the killing of Tarrant County Deputy Sheriff Malcolm Davis being particularly significant.

Davis’s close relationship with Mayor Tate’s family added a layer of personal tragedy to the larger narrative of Bonnie and Clyde’s downfall. His murder spurred a wave of anger and determination among lawmen, igniting a relentless hunt for the outlaws.

The Implications for Law Enforcement

The brutal killings of law enforcement officers by Bonnie and Clyde sent shockwaves through Texas, leading to heightened cooperation among various police forces. The sacrifices made by officers like Malcolm Davis underscored the dangers faced by law enforcement during this tumultuous period and led to a paradigm shift in how authorities approached policing.

Communities such as Grapevine began to view police officers not merely as enforcers of the law but as protectors of the populace. This dynamic fostered a stronger alliance between officers and local residents—a bond born out of shared grief and collective responsibility.

Grapevine’s Legacy Post-Bonnie and Clyde

After the dust settled from Bonnie and Clyde’s violent end, Grapevine continued to evolve. The memories of the outlaw couple remained ingrained in the town’s culture, becoming a point of pride for some and a cautionary tale for others.

Today, Grapevine actively embraces its historical connection to Bonnie and Clyde as it preserves the narratives of the past. The tales are not simply stories of crime but rather reflections of resilience and community spirit.

The city’s ongoing commitment to preserving its history showcases how the legacy of an infamous couple can transform from infamy to a rich tapestry of storytelling and cultural identity.

Bonnie & Clyde: Bonnie Parker, Clyde Barrow, and the Barrow Gang FBI Files, Court Documents and Histories

1,576 pages of FBI files and U.S. District Court for the Dallas Division of the Northern District of Texas documents covering Bonnie Parker, Clyde Barrow, and the Barrow Gang, and published histories on Bonnie and Clyde.

FBI FILES

948 pages of FBI files covering Bonnie Parker, Clyde Barrow, and the Barrow Gang. These files, once thought to be lost, were discovered and eventually declassified and released by the FBI in May 2009. Previously only three pages of FBI files on Bonnie & Clyde were known to remain in the custody of the FBI. These “lost” files were released in their entirety, without redactions. The files contain details about the Barrow Gang’s crime spree not previously published before the discovery of these files. These files describe the Bureau’s involvement in the pursuit of Bonnie and Clyde, which began almost exactly a year before their deaths.

In late 2006, a FBI historian working out the Dallas Field Office recovered these files. They had been thrown in the trash many years earlier to make space for new files. At that time, a FBI employee retrieved the files from the trash. The FBI historian discovered their existence while preparing a historical exhibit in Dallas. The files then entered the review process for declassification.

FBI FILES CONTENTS:

United States Department Of Justice Bureau of Investigation Dallas Field Office File# 26-4114:

Dallas Field Office File# 26-4114 – Memos

Dallas Field Office File# 26-4114 – Section 1

Dallas Field Office File# 26-4114 – Section 2

Dallas Field Office File# 26-4114 – Section Sub A

The files date mostly from May 5, 1933 to February 1, 1935. The files show on how many different levels law enforcement worked together closely in the hunt for the Barrow Gang. The files show the sharing of information, leads, and informants, with the FBI often acting as a clearinghouse for the spread of information across the Midwest. New Orleans Division Special Agent Lester Kindell, for example, played a central role in this cooperative effort to track the fugitives in Louisiana and parts of Texas, joining hands with former Texas Ranger Frank Hamer and other local law enforcement agencies. Kindell was also closely involved in discussions that led to the final confrontation with Bonnie and Clyde, although he did not participate in the fatal ambush.

Within the collection each file section is named as the original file was named and includes all pages that were in that file, in the arrangement released by the FBI.

Highlights among the files include:

Memos detailing the investigation of two stolen cars, which lead to FBI getting involved in the case. A bureau report on the April 13, 1933 Joplin Missouri police shoot-out. Reports of information obtained from informants days before Parker and Barrow were killed. Reports tell of the extent of the injuries Bonnie sustained during the gang’s run. Several handwritten letter pages from Texas Ranger Frank Hamer on The New Inn Shreveport, Louisiana hotel stationary.

A June 30, 1933 letter from George T. Corry, sheriff of Collingsworth, Texas to the Bureau concerning his being taken on a ride, kidnapped, by the Barrow Gang. A July 8, 1933 report with 8 pages of detailed information of the gang’s kidnapping of George T. Corry, sheriff of Collingsworth, Texas and Wellington, Texas Chief of Police Paul Hardy. A July 10, 1933 memo gives an account of the appearance at the Bureau’s Dallas office of the brother of Constable J. W. Harryman, who was killed at the Joplin shootout by Barrow Brothers, who stated his intention to kill the Barrow Brothers.

An August 17, 1933, 26-page report on the gang’s activity from July 20, 1933 to July 27, 1933. The report summarizes the various leads and witness interviews during this stretch of the hunt for the Barrow Gang. The report contains a death bed interview of Marvin “Buck” Barrow. Buck received wounds to the head during the Platte City shootout. He received additional wounds in the back during a shootout in an open field near Dexter, Iowa. He died at Kings Daughters Hospital in Perry, Iowa on July 29, 1933. The agent who interviewed Buck described him as being cynical. Although near death, the report says that he would laugh heartily on the retelling of his escapades. The report also gives the results of a jail house interview with Buck’s widow, Blanche Barrow. Later in the report is the transcript of the 5-page confession Blanche gave on August 16, 1933.

A November 20, 1933 report covers the informant information that lead to the failed “Sowers Ambush.” Dallas County authorities learned that Barrow and Parker would be attempting to meet up with family members near Sowers, Texas. Waiting for them were Sheriff “Smoot” Schmidt, Ted Hinton, Ed Caster and Bob Alcorn. When they spotted Bonnie and Clyde in a black 1933 Ford V8 coupe they opened fire. Although wounded, Bonnie and Clyde were able to escape and steal another car at gunpoint.

A December 23, 1933 report conveying information from a nurse friend of Bonnie, Hattie Crawford, who says she treated Clyde’s gunshot wounds. A 5-page, December 14, 1933 memo recounts the information given in an interview by captured Barrow Gang member William Daniel Jones.

A January 5, 1934 report indicating a willingness on the part of Bonnie’s brother, Hubert “Buster” Parker, to give up Clyde if it meant saving Bonnie.

Memos, telegrams, and handwritten reports from mid-January 1934 chronicle the Barrow Gang going to the Texas State Prison system’s Eastham State Farm and launching a raid freeing Raymond Hamilton (Floyd Hamilton’s brother), Joe Palmer, Henry Methvin, and Hilton Bybee. During the escape one guard was killed and another wounded. A January 17, 1934 Bureau report written at Eastham State Farm concerning information gain from interviews at the prison. A March 29, 1934 report gives details of gang’s actions after the Eastham State Farm Prison breakout, with information provided by a recaptured Hilton Bybee.

An April 21, 1934 memo following information concerning Clyde Barrow’s attempts to contact a former girlfriend.

An April 24, 1934 memo shows that Bailey Tynes, Clyde Barrow’s cousin, was paid $4.00 a day as a bureau informant.

An April 24, 1934 memo to J. Edgar Hoover tells of the immunity deal that Texas authorities made with Methvin family “provided the Methvins would place Barrow and Bonnie Parker on the spot.”

A May 3, 1934 Bureau report contains a 5-page transcript of a signed statement by a captured James Mullen, giving an account of the Gang’s situation since the Eastham prison breakout.

From May 3 to May 22, 1934 a variety of typed and handwritten memos, letters, and telegrams indicate a tighter, ceaseless, and destined hunt for Bonnie and Clyde.

FBI Headquarters Interesting Case Memorandum

These three pages titled, “Clyde Champion Barrow, with aliases, and Bonnie Parker, with aliases, National Motor Vehicle Theft Act, Interesting Case Memorandum,” were once the only Bonnie & Clyde FBI files known to exist within the Bureau. They were produced in 1934 and revised in 1984. This three-page memo was intended to provide a clear summary of their backgrounds, crimes, and law enforcement’s hunt to bring them to justice. It was meant to be used as background for interested journalists, researchers, and FBI employees.

COURT DOCUMENTS

Bonnie & Clyde – Barrow Gang Criminal Case File – U.S. District Court for the Dallas Division of the Northern District of Texas documents covering the Barrow Gang. Includes copies of indictments, detail of charges, are records of arraignment.

United States v. Raymond Hamilton, et. al Grand Jury Indictment – U.S. District Court for the Dallas Division of the Northern District of Texas – Grand jury true bill in the criminal case of Unites States v. Raymond Hamilton, Clyde C. Barrow, Bonnie Parker, Henry Methvin, Joe Palmer, and Hilton Bybee. The defendants were accused of theft of weapons from the Texas National Guard armory.

United States v. Mary Pitts, alias Mary O’Dare, et. al – U.S. District Court for the Dallas Division of the Northern District of Texas – This file consists of the criminal case United States v. Mary Pitts, alias Mary O’Dare, et. al. The charges were conspiring to harbor and conceal Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker

Jesse Warren v. Henderson Jordan – This file covers the court case Jesse Warren v. Henderson Jordan, at issue was ownership of the automobile that Clyde Barrow stole and was killed in.

ADDITIONAL MATERIAL

Fugitives; The story of Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker

This 260-page book was published in 1934, full title: Fugitives The Story of Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker as Told by Bonnie’s Mother (Mrs. Emma Parker) and Clyde’s Sister (Nell Barrow Cowan)Compiled, Arranged, and Edited by Jan I. Fortune. This book was published just three months after the deaths of Barrow and Parker. While probably not holding up to journalistic standards of today, it is still two interesting family stories from both the Barrow and Parker family. Reference is made to the contents of letters and diary entries.

Fugitives purported to tell the story of Bonnie & Clyde from a more sympathetic, family point of view; author Jan Fortune had interviewed Nell Barker (Clyde’s sister) and Emma Parker (Bonnie’s mother). But Fortune was a screenwriter, not a historian.

According to James R. Knight’s author of Bonnie and Clyde: A Twenty-First-Century Update, both Barker and Emma Parker denied to him making many of the statements attributed to them. Nonetheless Fugitives further softened Bonnie & Clyde’s image as hard-core criminals, suggesting among other things that they were products of their environment. “Now that they were dead,” according to Knight, “it became possible [for Fortune and others] to begin to show them as complex, contradictory human beings instead of cartoon-character gangsters… The swing of the pendulum to the other extreme of John Steinbeck-type folk heroes took a little longer.”

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form – Bonnie & Clyde Garage Apartment, Joplin Missouri

National Parks Service 39-page report on the granting into the National Register of Historic Places of the Bonnie and Clyde Joplin hideout. The Joplin hideout was designated a national historic place on May 15, 2009. The report includes detailed information about the location and physical aspects of this garage apartment at 3347 1/2 Oak Ridge Drive. It includes a well researched 14-page history of the Joplin Shootout. The report includes 8 photos of the apartment taken in February 2009.

BACKGROUND

When Bonnie met Clyde in January 1930, she was 19 and married to an imprisoned burglar, who she married when she was 15. Clyde was arrested a few days after they met for burglary. He escaped jail in Waco, Texas using a gun Bonnie smuggled to him. Clyde was recaptured and was sent back to prison. Clyde was paroled in February 1932. He soon returned to a life of crime, apparently murdering an Oklahoma sheriff and a storekeeper. By August, Bonnie and Clyde were together for good and making news, as they were pursued across Texas, Oklahoma, Missouri, Louisiana, Arkansas, Kansas, Iowa, and Illinois.

At the core of the Barrow Gang were Bonnie and Clyde. At different times the group included others such as Clyde’s older brother Marvin “Buck” Barrow and his wife Blanche, William Daniel Jones, Raymond Hamilton, Henry Methvin, Joe Palmer, Mary O’Dare, and others.

Before dawn on May 23, 1934, a posse composed of police officers from Louisiana and Texas, including Texas Ranger Frank Hamer, concealed themselves in bushes along the highway near Sailes, Louisiana. In the early daylight, Bonnie and Clyde appeared in an automobile. They slowed down when they came across Henry Methvin’s father Ivy standing beside his truck as if it was broken down. It was a trap. Ivy ducked away, and the officers opened fire. Bonnie and Clyde were killed instantly.

The Barrow Gang is generally attributed with the responsibility for the deaths of 12 individuals, including nine law enforcement officers:

John Bucher, Hillsboro, Texas: April 30, 1932 – On April 27, Bucher opened his Hillsboro store after it was closed for two men who claimed they needed guitar strings for a musical performance. He was fatally shot while making change.

Eugene C. Moore, Atoka, Oklahoma: August 5, 1932 – Undersheriff Moore and Sheriff Charles Maxwell were investigating a disturbance at an outdoor dance near the rural Oklahoma community of Stringtown, when they encountered two men suspiciously milling about parked cars. Undersheriff Moore was killed instantly, while Sheriff Maxwell was seriously wounded.

Howard Hall, Sherman, Texas: October 11, 1932 – Hall, a butcher at a small Sherman grocery, attempted to thwart a robbery of the store by Clyde Barrow.

Doyle Johnson, Temple, Texas: December 26, 1932 – Johnson attempted to stop the theft of his wife’s new car and was shot.

Malcolm Davis, Dallas, Texas: January 6, 1933 – Tarrant County Deputy Sheriff Davis was among several law officers caught in a gunfight with Barrow Gang members during a West Dallas stakeout of Raymond Hamilton’s sister’s house.

Harry McGinnis, Joplin, Missouri: April 13, 1933 – Detective McGinnis received multiple gunshot wounds as he and other officers approached a Joplin, Missouri home used as a hideout by the Barrow Gang.

John Wes Harryman, Joplin, Missouri: April 13, 1933 – Constable Harryman was also shot at the Joplin hideout.

Henry D. Humphrey, Alma, Arkansas: June 26, 1933 – City Marshal Humphrey was shot and killed at a roadblock north of Alma while attempting to stop a car carrying members of the Barrow Gang.

Major Crowson, Huntsville, Texas: January 16, 1934 – Crowson, a guard at the Eastham State Farm was shot and killed during the Barrow Gang raid to free inmates at the prison.

E.B. Wheeler, Grapevine, Texas: April 1, 1934 – Texas Highway Patrolman Wheeler was killed on Easter morning when he approached a Barrow Gang car stopped on the side of the road.

H.D. Murphy, Grapevine, Texas: April 1, 1934 – Texas Highway Patrolman Murphy was Wheeler’s partner; he was also killed at Grapevine.

Calvin Campbell, Commerce, Oklahoma: April 6, 1934 – Constable Calvin was shot and killed while approaching a Barrow Gang car stuck in a muddy road. Calvin’s partner was taken hostage. Campbell, a 61-year-old single father of eight, is believed to be the last Barrow Gang victim to be killed.