A12 CIA Spy Plane: Lockheed Blackbird Project Oxcart Files

$19.50

A12 CIA Spy Plane: Lockheed Blackbird Project Oxcart Files

Description

A-12 OXCART: Development, Deployment, and Demise

Timeline of Main Events:

- Late 1950s: Lockheed begins preliminary work on a successor to the U-2, codenamed “Archangel”. Internal Lockheed designations evolve from Archangel-1 to A-1, A-2, etc. The A-12 is Lockheed’s 12th design in this progression.

- 1957: Richard Bissell, concerned about the U-2’s vulnerability, forms the Land Committee to seek a successor.

- Early 1958: Bissell asks Lockheed and Convair to submit designs for a high-speed reconnaissance aircraft.

- July 23, 1958: Kelly Johnson presents his Mach 3.0 design concept to the Land Committee.

- September 1958: The Land Committee reviews design proposals, rejecting multiple ideas including a Navy ramjet-powered design and a Lockheed hydrogen-powered design. They continue to evaluate Convair’s “FISH” and Lockheed’s A-2 designs.

- Late November 1958: The Land Committee concludes that building an aircraft with high speed and altitude to evade radar detection is feasible. They recommend further development.

- December 17, 1958: Allen Dulles and Richard Bissell brief President Eisenhower on the progress of the U-2 successor program, mentioning competing projects from Lockheed and Convair.

- Summer 1959: Lockheed and Convair submit detailed proposals. Lockheed proposes the A-11, while Convair proposes the “FISH” parasite aircraft.

- June 1959: The Air Force cancels the B-58B project, a crucial part of Convair’s FISH proposal.

- July 14, 1959: The Land Committee rejects both the A-11 and the FISH designs.

- July 20, 1959: President Eisenhower approves the high-speed reconnaissance aircraft project, despite no acceptable design.

- Late Summer 1959: Lockheed submits the modified A-12 design, and Convair offers the KINGFISH design.

- August 20, 1959: Lockheed and Convair submit proposals to a joint selection panel.

- Late August 1959: Project GUSTO is replaced by Project OXCART.

- September 14, 1959: CIA awards Lockheed a four-month contract for anti-radar studies, aerodynamic tests and engineering designs for the A-12.

- January 1960: Lockheed demonstrates a substantial reduction in the A-12’s radar cross section, but performance is reduced. Kelly Johnson increases the aircraft’s fuel load, making it possible to achieve the target altitude of 90,000 feet.

- January 26, 1960: The CIA authorizes the construction of 12 A-12 aircraft.

- February 11, 1960: The CIA and Lockheed sign a contract for 12 A-12 aircraft.

- September 1960: Construction begins at Groom Lake (Area 51) to support the OXCART program.

- November 15, 1960: The new 8,500 foot runway is completed at Groom Lake.

- August 1, 1961: The forecast delivery date of the first A-12.

- January – February 1962: The first A-12, Article 121, is assembled and tested at Burbank.

- February 26, 1962: Article 121 is transported from Burbank to Groom Lake.

- April 25, 1962: Lou Schalk makes an unannounced unofficial short test flight of Article 121.

- April 26, 1962: Schalk makes a 40 minute test flight of Article 121, with some damage to the airframe.

- April 30, 1962: The first official flight of the A-12, witnessed by CIA officials, with the wheels up, reaches 30,000 feet.

- May 2, 1962: The A-12 breaks the sound barrier, achieving Mach 1.1.

- June 1962: Four more aircraft, including a two-seat trainer, arrive at Groom Lake.

- October 5, 1962: An A-12 flies with one J75 engine, and one J58 engine.

- 1963: A-12s equipped with J58 engines attain Mach 3.2.

- May 24, 1963: The first A-12 crash occurs near Wendover, Utah; pilot ejects safely.

- June 1964: The last A-12 is delivered to Groom Lake. 18 aircraft were built, including 13 A-12s, 3 YF-12As and 2 M-21s.

- July 9, 1964: Article 133 crashes during landing, pilot ejects safely.

- December 28, 1965: Article 126 crashes immediately after takeoff, pilot ejects safely.

- January 27, 1965: The A-12 makes its first long-range high speed flight, 75 minutes above Mach 3.1.

- August 3, 1965: The Office of Special Activities’ Director of Technology meets with Kelly Johnson to discuss OXCART’s problems.

- November 20, 1965: Final validation flights for OXCART deployment are completed.

- November 22, 1965: Kelly Johnson declares the A-12 ready for operational use.

- 1965-1966: Ongoing debate about deploying the A-12. The JCS and PFIAB supported the CIA’s advocacy of deployment.

- August 12, 1966: President Johnson sides with the 303 committee against deployment of the A-12 on Okinawa.

- December 21, 1966: An A-12 sets a speed and distance record over the continental US.

- December 28, 1966: The decision is made to terminate A-12 operations by June 1, 1968.

- January 5, 1967: An A-12 crashes after running out of fuel, the pilot is killed in ejection.

- May 16, 1967: President Johnson approves the use of the A-12 for tactical intelligence.

- May 1967: A-12s are deployed to Kadena Air Base on Okinawa, Japan and BLACK SHIELD is declared operational.

- May 31, 1967: The first BLACK SHIELD mission is flown over North Vietnam.

- July 1967: BLACK SHIELD mission data confirms that no surface-to-air missiles had been deployed in North Vietnam.

- October 28, 1967: A North Vietnamese SAM site fires a missile at an A-12, but it is unsuccessful.

- February 1968: Lockheed is ordered to destroy all tooling used for A-12 production.

- May 1968: The first SR-71 arrives at Kadena to replace the A-12s.

- May 8, 1968: Jack Layton flies the final operational mission of an A-12, over North Korea.

- June 4, 1968: An A-12 is lost over the Pacific Ocean during a functional check flight, the pilot (Jack Weeks) is lost.

- June 21, 1968: Frank Murray makes the final A-12 flight to Palmdale, California.

- Summer 1968: The OXCART program officially ends, with no advanced successor ready.

Cast of Characters:

- Richard M. Bissell: CIA official, director of the U-2 program, and the initial champion of a successor aircraft. He formed the Land Committee and oversaw the early development of the OXCART project.

- Clarence “Kelly” Johnson: Lead designer at Lockheed’s Skunk Works. He was responsible for the design of the A-12 (and the U-2 before it). He was deeply involved in all aspects of the design, testing, and problem-solving of the A-12, going on-site at Area 51 in the middle of development to resolve performance and reliability issues. He often referred to the aircraft as “the Article.”

- Louis Schalk: Lockheed test pilot. He performed the first unofficial and official flights of the A-12.

- Allen Dulles: Director of Central Intelligence (DCI) during the project’s early stages. He supported the development of the A-12 and briefed President Eisenhower on the program.

- President Dwight D. Eisenhower: President of the United States who approved the OXCART project and its funding after briefings from Allen Dulles and Richard Bissell.

- Edward Purcell: Member of the Land Committee who proposed the cesium additive to fuel to reduce radar cross section.

- John McCone: Director of Central Intelligence, who believed that A-12 should be used over the Soviet Union, and brought the issue to President Kennedy.

- President John F. Kennedy: President of the United States, skeptical about overflights of the Soviet Union, and hoping for better reconnaissance from existing resources.

- Robert McNamara: Secretary of Defense who expressed doubt about the utility of the OXCART program and suggested an alternative.

- President Lyndon B. Johnson: President of the United States who, after initially rejecting the proposal, approved the deployment of A-12s for the Black Shield program.

- William F. Raborn: Director of Central Intelligence, who pushed for the A-12 deployment to Okinawa.

- Richard Helms: Director of Central Intelligence, who got President Johnson’s approval for Black Shield deployment.

- Mel Vojvodich: Pilot who flew the first BLACK SHIELD operational mission over North Vietnam.

- Jack Layton: Pilot who flew the final A-12 mission over North Korea.

- Jack Weeks: Pilot who was lost when his A-12 crashed over the Pacific Ocean.

- Frank Murray: Pilot who made the final flight of an A-12, to Palmdale, California.

- Donald Quarles: Air Force Secretary who attended the briefing of President Eisenhower in December 1958.

- James Killian: Presidential Service Advisor who attended the briefing of President Eisenhower in December 1958.

- Land: Member of the Land Committee, present at the briefing of President Eisenhower in December 1958.

- Purcell: Member of the Land Committee, present at the briefing of President Eisenhower in December 1958.

- Vance: Deputy Secretary of Defense who discussed the growing hazards confronting current aerial reconnaissance methods with DCI McCone and Secretary of Defense McNamara.

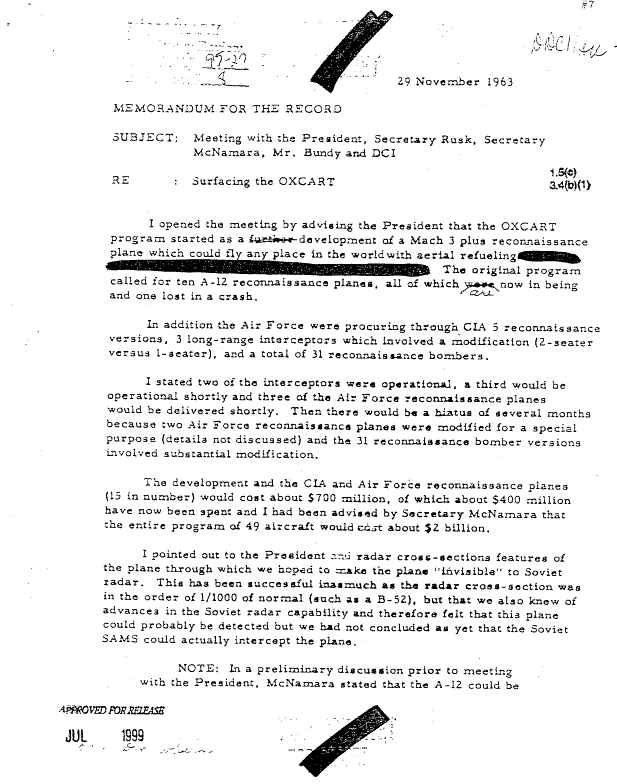

This extensive collection of CIA documents—4,179 pages of memos, letters, reports, and manuals—details the Lockheed A-12 Blackbird’s development, testing, and operational history.

The A-12, a reconnaissance plane built by Lockheed’s Skunk Works under Clarence “Kelly” Johnson’s direction for the CIA, was in production from 1962 to 1964 and active from 1963 to 1968. This single-seat aircraft, which first flew in April 1962, was the prototype for the YF-12 and the SR-71 Blackbird. The program concluded in June 1968, following its final mission in May.

In the spring of 1962, Lockheed test pilot Louis Schalk launched a groundbreaking aircraft from Nevada. Its unusual appearance—an exceptionally long, slender body, massive engines, a pointed nose, and unusually small swept-back wings—would have been striking. This revolutionary plane’s capabilities—supersonic flight over 3,000 miles without refueling and high-altitude cruising at low fuel—were unknown at the time. Lockheed’s work on a U-2 replacement, starting in the late 1950s, initially used the codename “Archangel,” a continuation of the U-2’s “Angel” designation. Internal Lockheed designations evolved with design changes, progressing from Archangel-1 to Archangel-2, and so on. These were eventually shortened to A-1, A-2, etc. The A-12 represented the twelfth iteration of this design process. Despite this, many records and references utilize the aircraft’s alternative name, “the Article,” favored by Clarence Johnson. The collection includes CIA A-12 files. Extensive CIA documentation (437 pages, 1959-1991) details the A-12 Oxcart program, including its organization, secrecy measures, and contingency plans. Memos reveal discussions between high-ranking officials, such as John McCone and Robert McNamara, regarding President Kennedy’s stance on overflights of the Soviet Union. The documents also track the spread of knowledge about the project, cover A-12 accidents, and President Johnson’s briefings. Further reports detail efforts to achieve promised speed records and assess potential Chinese reactions to overflights. The collection includes accounts of Black Shield missions and three classified CIA histories of the program.

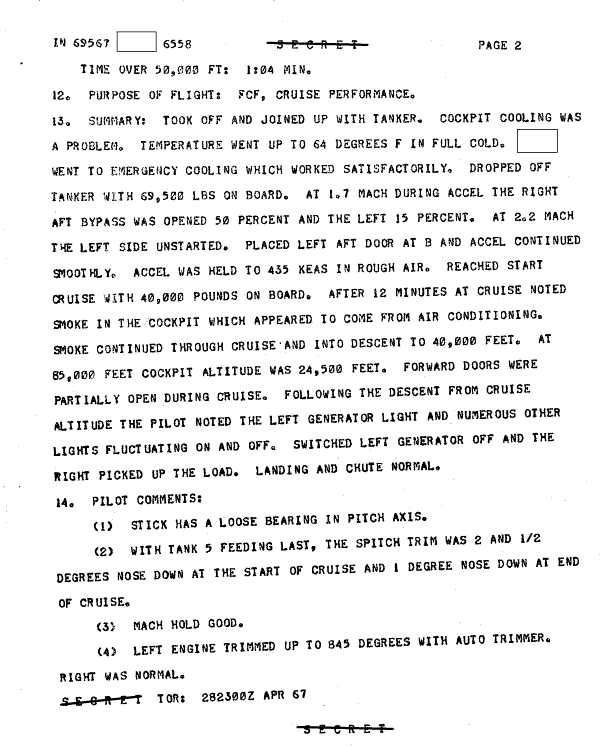

Separate flight logs (568 pages, March 20, 1963 – September 16, 1967) record A-12 test flights at Andrews Air Force Base and Area 51.

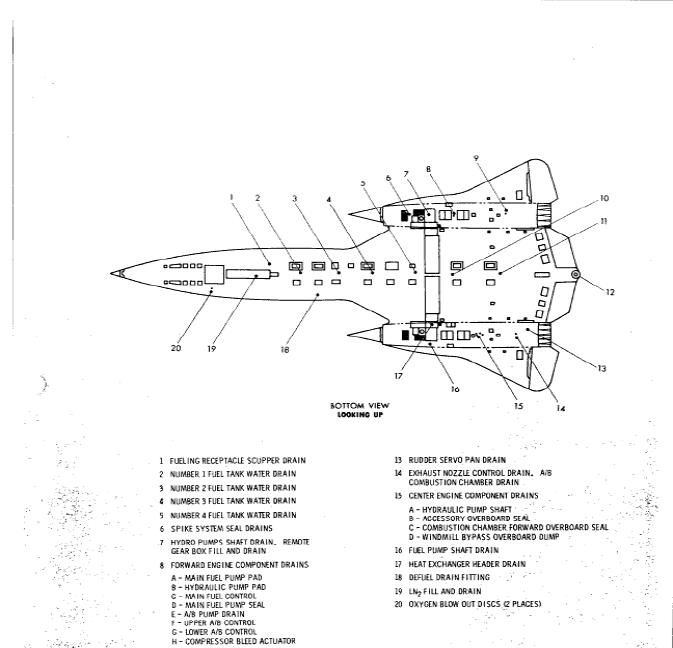

Finally, 784 pages of manuals provide detailed technical information on the A-12 Oxcart, covering various aspects from utility flight operations to ground crew procedures and photographic equipment. The June 15, 1968, A-12 Utility Flight Manual (459 pages) details aircraft systems, normal procedures, emergency procedures, auxiliary equipment, operating limitations, and flight characteristics. The manual describes various aircraft components, from engines and fuel systems to the ejection seat and landing gear. Normal flight operations, including pre-flight checks, takeoff, landing, and in-flight procedures, are outlined. Emergency procedures cover ground and in-flight scenarios, such as engine failure and fire. The manual also lists auxiliary equipment like communication systems and navigation equipment. Finally, it specifies operating limitations, including weight, speed, and altitude restrictions, and describes the aircraft’s flight characteristics under various conditions. The aircraft can operate in all weather conditions, including ice, rain, turbulence, thunderstorms, and extreme temperatures, and is capable of night flights.

Nine Lockheed Oxcart A-12 Black Shield mission reports, totaling 558 pages, detail reconnaissance flights from May 31, 1967, to January 26, 1968. These missions covered North Vietnam, China, Laos, and North Korea.

In China, the focus was on military bases, cities, infrastructure, storage facilities, communication systems, airfields, and naval ports.

North Vietnamese missions targeted surface-to-surface and surface-to-air missile systems, communication networks, industrial sites, infrastructure, naval ports, storage areas, chemical and biological warfare capabilities, and urban areas.

In North Korea, the missions concentrated on missile sites, airfields, military bases, communication systems, industrial facilities, infrastructure, ports, storage, and cities. One mission, BX6847, specifically investigated the USS Pueblo incident.

A concise history of the A-12 aircraft is requested. The U-2 aircraft originated in 1954, its development overseen by a CIA team led by Richard M. Bissell. Initially, CIA officials predicted the U-2 could safely fly over the Soviet Union for 18 to 24 months. However, this prediction proved overly positive after Soviet tracking and interception attempts. By August 1956, Bissell doubted the U-2’s survivability beyond six months. By the fall of 1957, Bissell’s concerns led him to request permission from Allen Dulles to form a committee, the Land Committee, to design a replacement aircraft. He sought this committee’s support to secure funding for a new project.

Lockheed, the U-2’s creator, and Convair, the B-58 bomber manufacturer, were the key players in the search for a successor. In early 1958, Bissell requested design proposals for a high-speed reconnaissance plane from both companies. Throughout the spring and summer of 1958, both firms developed designs without any government funding. After lengthy talks with Bissell about a faster U-2 replacement, Lockheed’s Kelly Johnson started designing a Mach 3 plane for altitudes exceeding 90,000 feet. Johnson unveiled this high-speed design to Land’s committee on July 23, 1958, who showed enthusiasm for his approach. Simultaneously, the Navy proposed a high-altitude reconnaissance craft: a ramjet-powered, inflatable rubber vehicle launched by balloon and rocket-boosted to ramjet operational speed. Bissell tasked Johnson with assessing the Navy’s idea. Three weeks later, having received further Navy specifications, Johnson’s calculations quickly revealed the design’s infeasibility; the balloon would need a mile-wide diameter to lift the vehicle, requiring a wingspan larger than one-seventh of an acre to support the payload. The Land committee reconvened in September 1958 to evaluate various aircraft concepts and select the most viable options. Several proposals were dismissed, including inflatable aircraft designs from the Navy and Boeing, and a hydrogen-powered plane from Lockheed. Two Kelly Johnson designs, a stealthy subsonic aircraft and a supersonic aircraft, were also rejected due to slow speed and high cost respectively. However, the committee greenlit Convair’s work on a Mach 4.0 ramjet aircraft, the FISH, designed to be launched from a modified B-58B bomber.

Following a subsequent review of Convair’s FISH and a new Lockheed reconnaissance aircraft in November 1958, the committee determined that developing a high-speed, high-altitude aircraft capable of evading radar was achievable. Consequently, they advised the Deputy Director of Central Intelligence (DCI) to request presidential approval and funding for continued research and testing. On December 17, 1958, Allen Dulles and Richard Bissell updated the President on the development of a U-2 replacement, alongside several advisors and officials. Dulles highlighted the U-2’s successes and predicted a global role for its successor, emphasizing its improved evasion capabilities.

Bissell then outlined two competing designs from Lockheed and Convair, focusing on the launch method debate. He projected the next stage would involve detailed engineering, culminating in a 12-aircraft order costing approximately $100 million. This funding secured, Lockheed and Convair were instructed to submit comprehensive plans.

By summer 1959, both companies had provided their proposals. Lockheed’s June submission detailed the ground-launched A-11, a Mach 3.2 aircraft with a 3,200-mile range, 90,000-foot altitude, and a January 1961 completion target. Despite prioritizing speed and performance over stealth, the A-11’s radar signature, while not ideal, exceeded that of Convair’s smaller design. Convair suggested a small, piloted reconnaissance craft, powered by ramjets, launched from a modified B-58B bomber. This experimental aircraft, known as FISH, would be a unique lifting body design with minimal radar visibility, capable of Mach 4.2 flight at high altitude (90,000 feet) and covering a distance of 3,900 miles. Two Marquardt ramjets would propel it to supersonic speed over the target, while Pratt & Whitney turbojets would handle the return flight. Heat-resistant Pyroceram would be used in the ramjet nozzles and wing edges to manage extreme temperatures and reduce radar detection. Convair projected completion by January 1961.

Convair’s plan relied on two major unknowns. The most critical was the unproven ramjet technology; no aircraft could then launch and accelerate a large ramjet-powered vehicle to ignition speed. Wind tunnel testing was insufficient to guarantee operational success. Furthermore, the B-58B bomber, planned to launch FISH at high speed and altitude, was still under development. Convair’s B-58B project was cancelled by the Air Force in June 1959, severely hindering their proposal. Adapting the existing B-58A proved too expensive and technically challenging. Furthermore, the Air Force was reluctant to sacrifice two of its limited supply of advanced bombers. Even without the cancellation, the Convair plan was likely unworkable due to the added weight of the FISH system preventing the necessary speed for ignition.

Consequently, Convair’s design was impractical, and Lockheed’s, with its large radar signature, was also deemed unsuitable by the Land committee. The committee rejected both proposals on July 14, 1959, and the competition continued. Lockheed continued refining their design for better stealth, while Convair received a new CIA contract to develop a twin-engine, air-breathing aircraft meeting similar specifications.

Subsequently, following the Land committee’s advice, both companies integrated the powerful Pratt & Whitney J58 engine into their designs. This engine, initially intended for the Navy’s P6M Seamaster, became available after the Navy’s cancellation of that program in 1958. The Land committee hadn’t finalized a design, but assured President Eisenhower on July 20, 1959, that progress was satisfactory. Worried about the U-2’s weaknesses and the photo satellite project’s setbacks, the President approved the high-speed reconnaissance plane.

By late summer 1959, Convair and Lockheed had submitted new U-2 successor designs. Convair’s KINGFISH leveraged technology from other aircraft, featuring a stainless steel skin, a flat wing, and an ejection capsule, eliminating the need for pressure suits. Its J58 engines were housed within the fuselage, minimizing radar detection, further aided by fiberglass engine intakes and Pyroceram leading wing edges.

Lockheed’s revised design, the A-12, also used two J58 engines. Its key radar reduction feature was a cesium fuel additive, suggested by Edward Purcell. To reduce weight, Kelly Johnson opted for a titanium alloy instead of steel, as aluminum couldn’t withstand the extreme heat at Mach 3.2. Lockheed and Convair presented their aircraft designs to a government panel in August 1959. While Lockheed’s design excelled in most areas, including cost, Convair’s was less detectable by radar. Initially, some CIA members preferred Convair’s design due to its stealth capabilities. However, the Air Force ultimately swayed the decision in Lockheed’s favor, citing Convair’s past performance issues. Lockheed’s successful U-2 project and its secure development environment also played a role. The CIA chose Lockheed’s A-12. Despite this, the panel’s radar detection concerns led to a Lockheed mandate to improve the A-12’s stealth by January 1960. A four-month contract for further research, under the new codename Project OXCART, was awarded to Lockheed in September 1959. By mid-January 1960, Lockheed successfully showed that their design innovations significantly decreased the OXCART’s radar visibility. However, this improvement negatively impacted the plane’s capabilities, disappointing Richard Bissell, who had guaranteed a specific flight altitude to President Eisenhower. Kelly Johnson countered this by suggesting a weight reduction and increased fuel capacity, enabling the aircraft to reach the required 90,000-foot altitude. He then recorded that the project’s difficulty had increased even further, exceeding initial expectations.

Bissell approved these modifications, leading to the CIA’s authorization for the construction of twelve aircraft by January 26th, officially contracted on February 11th, 1960. The initial project cost was $96.6 million, but this proved unrealistic due to unforeseen technical challenges. Anticipating problems with titanium construction, the CIA included a cost-adjustment clause in the contract. This clause was frequently used over the next five years as the A-12’s expenses more than doubled the original budget. Lockheed’s Burbank facility was unsuitable for OXCART testing due to its short and publicly accessible runway. The perfect location needed to be isolated, far from air traffic, easily reached by air, have consistently good weather, ample space for personnel, proximity to an Air Force base, and a long runway (at least 8,000 feet), but no such place existed.

After reviewing ten slated-for-closure Air Force bases, Richard Bissell chose Groom Lake (Area 51). While lacking sufficient housing, fuel storage, and runway length for OXCART, its remote location significantly improved security, and construction could address the shortcomings. Construction started in September 1960, with workers transported via C-47 flights from Burbank to Las Vegas, then to the site.

The new 8,500-foot runway was finished by November 15, 1960. Kelly Johnson opposed the standard Air Force runway design with its frequent expansion joints, fearing vibrations. He proposed, and they implemented, a staggered, wider section design to minimize these vibrations by aligning most joints with the aircraft’s roll. Eighteen miles of highway were repaved to accommodate heavy fuel tankers supplying the base. The Navy provided extra buildings; three disassembled hangars and over 100 housing units were relocated to Groom Lake. All necessary infrastructure was completed before the A-12’s scheduled arrival on August 1, 1961.

The initial A-12 aircraft, designated Article 121, underwent assembly and testing in Burbank during the first two months of 1962. Following its development and manufacture at the Skunk Works, it was moved to the Groom Lake test facility (Area 51).

Due to its inability to fly there, the A-12 was partially dismantled and transported on a custom-built trailer costing almost $100,000. The fuselage, minus wings, was packaged into a massive 35-foot-wide, 105-foot-long shipment. To ensure safe passage, obstacles like road signs and trees were cleared along the route. The journey from Burbank began on February 26, 1962, concluding two days later. Lockheed’s Lou Schalk piloted the A-12’s initial test flight. This unannounced, unofficial flight on April 25th, 1962, a Lockheed custom, was brief and problematic due to faulty control connections. These issues were quickly resolved. The following day, Schalk completed a longer, 40-minute flight, but the aircraft lost several aerodynamic components. Repairing these took four days.

The aircraft’s official maiden voyage happened on April 30th. With the repairs finished, the A-12, also known as the OXCART, took flight, observed by CIA personnel. This flight, the first without the landing gear down, reached 30,000 feet at a speed of 170 knots, eventually topping out at 340 knots during its 59-minute duration. Kelly Johnson praised its exceptional smoothness. Finally, on May 2nd, 1962, the A-12 surpassed the speed of sound, reaching Mach 1.1. Additional planes, including a training aircraft, reached the testing facility before year’s end. A June 26, 1962, shipment resulted in a collision between the oversized transport and an oncoming bus. To avoid legal complications, project leaders swiftly paid $4,890 for the bus repairs.

On October 5, 1962, an A-12 successfully flew using a combination of J75 and the new J58 engines. In 1963, J58-powered A-12s reached speeds of Mach 3.2, but a crash also occurred that year. A pilot ejected safely from an A-12 on May 24, 1963, after experiencing faulty airspeed readings; the aircraft was lost near Wendover, Utah. The incident was publicly attributed to an F-105, and all A-12s were temporarily grounded for investigation. An ice blockage in the airspeed sensor was determined to be the cause.

The final A-12 arrived at Groom Lake in June 1964. The A-12 program produced 18 aircraft: 13 A-12s, three YF-12A interceptors for the Air Force (outside the OXCART program), and two M-21s. One of the A-12s was a dual-seat trainer. The YF-12, a small-scale version of the CIA’s A-12 OXCART spy plane, made its maiden flight in 1962. Lockheed persuaded the Air Force that a modified A-12 offered a cheaper substitute for the cancelled XF-108, leveraging existing design and development. Consequently, the Air Force agreed in 1960 to receive three A-12 airframes, reconfigured as YF-12A interceptors. Key alterations included a redesigned nose to integrate the XF-108’s AN/ASG-18 fire-control radar and a second cockpit for the radar operator. These nose changes necessitated ventral fins for stability. Lastly, the reconnaissance equipment bays were repurposed to carry missiles. Subsequent testing resulted in the loss of two more A-12 aircraft. A malfunctioning pitch control system caused the crash of aircraft 133 on July 9, 1964, during landing. The pilot, ejected at a low altitude, survived thanks to a successfully deployed parachute. The incident remained unreported. Another A-12, number 126, crashed on December 28, 1965, immediately after takeoff due to faulty wiring in the stability augmentation system. Again, the pilot ejected safely, and the accident was kept secret. An investigation by CIA Director John McCone attributed the wiring fault to carelessness, ruling out sabotage.

The A-12 successfully completed its first long-distance, high-speed flight on January 27, 1965. This 100-minute flight included 75 minutes at speeds exceeding Mach 3.1, covering 2,850 miles at altitudes between 75,600 and 80,000 feet. The OXCART program was showing promising results, with various key systems performing reliably. The OXCART’s increased performance led to new challenges. These were primarily caused by faulty wiring, which frequently caused malfunctions in various systems. The wiring’s materials couldn’t handle the extreme heat, movement, and stress. However, poor Lockheed maintenance also played a role in the aircraft’s issues.

Worried about delays, the Office of Special Activities’ technology director met with Kelly Johnson to address the OXCART’s problems. Johnson responded by increasing project oversight, personally overseeing the project’s development, and improving vendor relations. He significantly boosted electrical system supervision and strengthened quality control. Johnson attributed a third of the problems to design flaws, acknowledging the A-12’s complex systems but ultimately claiming the issues were resolved. OXCART’s final test flights concluded on November 20, 1965, successfully reaching Mach 3.29, an altitude of 90,000 feet, and maintaining speeds above Mach 3.2 for 74 minutes; the longest test flight lasted six hours and twenty minutes. On November 22nd, Kelly Johnson informed the Office of Special Activities that the aircraft was ready for deployment.

Three years and seven months after its maiden voyage in April 1962, the A-12 OXCART was operationally prepared, and its future missions needed defining.

While initially intended to replace the U-2 for Soviet overflights, this plan became questionable long before the A-12’s readiness. The 1960 U-2 incident made future Soviet overflights politically unfeasible, as Presidents Eisenhower and Kennedy publicly ruled them out. In July 1962, Secretary of Defense McNamara expressed doubt about the OXCART’s deployment, suggesting alternative reconnaissance programs could render it unnecessary. However, DCI McCone strongly countered, asserting his intention to utilize the OXCART for Soviet overflights. In April 1963, John McCone brought up the need for improved reconnaissance to President Kennedy, due to frequent equipment malfunctions and intelligence agencies’ urgent need for better imagery to verify claims about a Soviet anti-ballistic missile system. Kennedy, however, wasn’t persuaded by McCone’s proposal to use OXCART planes and hoped for improvements to existing methods.

Following the Cuban Missile Crisis, the A-12 aircraft was deemed unsuitable for missions over Cuba. However, as the OXCART’s capabilities advanced, its overseas deployment, especially in Asia where US military presence was expanding, was reconsidered. In March 1965, McCone, McNamara, and Vance discussed the increasing risks associated with existing aerial reconnaissance techniques.

With the escalating US troop deployment in South Vietnam during the summer of 1965, Southeast Asia became another potential area for OXCART missions. The threat of Soviet-made surface-to-air missiles to U-2 flights over North Vietnam prompted McNamara to inquire with the CIA in June 1965 about replacing U-2s with OXCART aircraft. The new CIA director, Admiral Raborn, responded that OXCART deployment over Vietnam was feasible once final testing was complete. The Far East operation, codenamed BLACK SHIELD, intended to station OXCART planes at Kadena Air Base in Okinawa. Initially, this involved rotating three aircraft for two-month stints twice annually, requiring 225 personnel. A permanent presence was the eventual goal. To prepare, the Department of Defense invested $3.7 million in Okinawan infrastructure and secure communications by early 1965.

The plan stalled for over a year. Throughout the first half of 1966, DCI Raborn repeatedly pushed for Okinawa deployment at various 303 Committee meetings, but unsuccessfully. While the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the President’s Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board backed the CIA’s proposal, high-ranking State and Defense officials deemed the political risks—primarily the near-certain revelation to Japan—too high, outweighing any potential intelligence benefits. President Johnson sided with the 303 Committee’s opposition to immediate deployment on August 12, 1966. Since combat missions were impossible, the focus remained on training. This resulted in better mission plans and flight techniques, shortening the Okinawa deployment time from three weeks to just over two. The A-12 continued to break records. A Lockheed pilot flew it over 16,000 kilometers across the U.S. in just over six hours on December 21, 1966, averaging nearly 2,700 kilometers per hour, despite slower refueling periods. This speed and distance record was unmatched.

The A-12 program was subsequently ended on June 1, 1968.

An A-12 crashed on January 5, 1967, due to a faulty fuel gauge. The pilot ejected but died because he couldn’t escape the ejection seat. To maintain secrecy, the Air Force falsely reported that an SR-71 was lost in Nevada. These crashes, including the three previous ones, weren’t caused by high-speed flight issues, but by common aircraft problems. It was suggested that the OXCART program collect tactical intelligence for Project Black Shield, driven by concerns in Washington about potential undetected deployment of surface-to-air missiles in North Vietnam. Following a presidential request for a solution, the CIA proposed using OXCART. Despite ongoing State and Defense Department reviews of the proposal’s political implications, CIA Director Helms secured presidential approval during a meeting on May 16th. The CIA immediately implemented the Black Shield plan to deploy OXCART to the Far East.

During May 1967, A-12 aircraft were transported to Kadena Air Base in Okinawa, marking the Black Shield unit’s operational status. Personnel and equipment were airlifted to Kadena starting May 17th. A first A-12 completed a six-hour, six-minute nonstop flight to Kadena on May 22nd, followed by a second on May 24th. A third A-12 departed on May 26th but experienced navigation and communication issues near Wake Island, necessitating an emergency landing. After repairs, the aircraft reached Kadena the next day. Thirteen days after President Johnson’s authorization, the Black Shield program was operationally ready on May 29, 1967. The next day, the team was mobilized for a mission. Mel Vojvodich piloted the inaugural Black Shield mission over North Vietnam. Despite heavy rain at the base, the flight proceeded as the weather over the target was clear. The OXCART aircraft, unaccustomed to such conditions, took off.

This first mission involved two flight paths, one over North Vietnam and another over the DMZ. The high-speed, high-altitude flight (Mach 3.1 at 80,000 feet) lasted three hours and 39 minutes. Seventy of the 190 known surface-to-air missile sites, along with nine other key targets, were photographed in North Vietnam. The lack of detected radar signals suggested the aircraft remained undetected by both Chinese and North Vietnamese forces.

Fifteen Black Shield missions were planned over the following six weeks, with seven actually executed. Only four missions encountered hostile radar. By mid-July 1967, the gathered intelligence led analysts to believe no surface-to-air missiles were deployed in North Vietnam. A total of 22 missions were flown from Kadena in 1967 in support of the Vietnam War. The A-12s (and later SR-71s) and their pilots earned the nickname “Habu” during their Okinawa deployment, a reference to a local venomous snake. Flights over North Vietnam typically refueled near Okinawa soon after takeoff, then again near Thailand before returning to base. These missions were remarkably fast, lasting only 12.5 minutes for a single pass and 21.5 minutes for two. The plane’s large turning radius sometimes led to unintended border crossings.

After landing, the film was initially flown to the US for processing. However, to speed up delivery of intelligence, a Japanese lab took over this task in late summer, providing images to commanders within a day.

On September 17, 1967, a surface-to-air missile site unsuccessfully targeted the aircraft. A successful missile launch finally occurred on October 28th, captured on film; however, countermeasures protected the plane.

Throughout 1968, the A-12s continued missions in Vietnam and assisted during the Pueblo incident. Lockheed destroyed A-12 production tools in February, anticipating the SR-71’s arrival. The SR-71s began replacing the A-12s at Kadena that year, with the final A-12 mission occurring over North Korea on May 8th. All remaining A-12s were then returned to California for storage. Jack Layton’s final A-12 flight concluded on May 8th, marking the aircraft’s retirement and subsequent replacement by the SR-71.

The A-12s completed 29 missions during their slightly more than one-year operational period, known as Operation Black Shield. An A-12 from Kadena Air Base, piloted by Jack Weeks, crashed in the Pacific near the Philippines on June 4th, shortly after the end of operations and before the entire fleet’s retirement, during a post-engine-replacement test flight; neither the aircraft nor the pilot were ever recovered.

The last A-12 flight, piloted by Frank Murray, landed in Palmdale, California on June 21, 1968. The CIA’s final high-altitude spy plane was the OXCART, though the Office of Special Activities briefly explored replacements in the mid-1960s. One such concept, Project ISINGLASS by General Dynamics, aimed to build a Mach 4-5 aircraft using technology from previous projects and the F-111, capable of flying at 100,000 feet.

General Dynamics finished its assessment in late 1964, but the OSA rejected it due to its vulnerability to Soviet defenses. Later, in 1965, McDonnell Aircraft proposed the more advanced Project RHEINBERRY (partially overlapping with ISINGLASS), a rocket-launched plane reaching Mach 20 and 200,000 feet, deployed from a B-52. However, the immense technical difficulties and costs led the CIA to abandon the project, as reconnaissance priorities shifted from planes to satellites. Therefore, when the OXCART program concluded in summer 1968, its replacement was not ready; only the older U2 remained.

The SR-71, designed to supersede the U-2 in strategic intelligence gathering, never fulfilled that role. Its limited use was confined to tactical intelligence, making minimal contribution to the CIA’s strategic goals. Alternative reconnaissance methods had already filled this niche by the time the SR-71 became operational, rendering this cutting-edge aircraft obsolete before its deployment.

Kelly Johnson’s 1967 journal entry reflects an earlier prediction, made in 1959, that only one generation of advanced reconnaissance aircraft would be needed before satellites took over; 30 SR-71s proved sufficient, negating the need for the additional OXCART planes.

The SR-71’s operational lifespan was shorter than the U-2’s, the very aircraft it was meant to replace. Unlike the U-2’s rapid deployment capabilities—a mission could be launched and completed within a week—the SR-71 demanded extensive logistical preparation. Its operational needs, including advanced fuel planning, emergency landing sites, and lengthy inertial guidance system setup, required days of work and hundreds of personnel, a stark contrast to the U-2’s far more streamlined operations.

The exceptionally fast, far-reaching, and high-flying OXCART reconnaissance plane significantly advanced aerospace technology beyond its impressive flight capabilities. Its true legacy lies in breakthroughs in aerodynamics, advanced plastics, engine technology, imaging systems, electronic defenses, pilot safety equipment, radar evasion, the use of non-metal components, and titanium fabrication techniques. These advancements propelled aerospace engineering forward and were instrumental in the development of later stealth aircraft.