Tokyo Rose FBI Files, Court Documents, Audio Recordings & Films

$0.00

Description

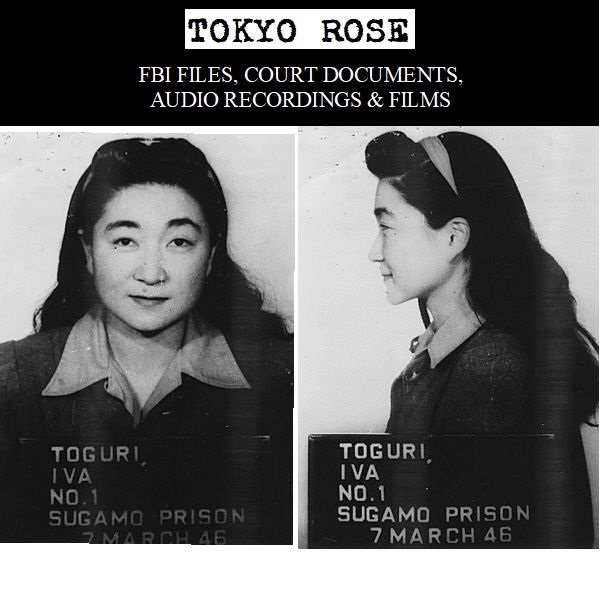

Iva Toguri D’Aquino: The “Tokyo Rose” Timeline

Detailed Timeline of Events

- July 4, 1916: Iva Ikuko Toguri is born in Los Angeles, California.

- 1899: Jun Toguri, Iva’s father, immigrates to the United States from Japan.

- 1913: Iva’s mother immigrates to the United States from Japan.

- 1940: Iva Toguri graduates from the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA).

- July 5, 1941: Toguri sails for Japan from San Pedro, California, without a U.S. passport, citing a visit to a sick aunt and plans to study medicine.

- September 1941: Toguri appears before the U.S. Vice Consul in Japan to apply for a U.S. passport for permanent return to the United States. Her application is forwarded to the State Department.

- December 7, 1941: Japan bombs Pearl Harbor, and the United States enters World War II. No further action is taken on Toguri’s passport application.

- Post-Pearl Harbor: Toguri applies for repatriation to the United States through the Swiss Legation in Japan but later withdraws the application, stating she will remain in Japan for the duration of the war. She enrolls in a Japanese language and culture school.

- Mid-1942 to Late 1943: Toguri works as a typist for the Domei News Agency.

- August 1943: Toguri obtains a second job as a typist for Radio Tokyo.

- November 1943 to August 1945: Toguri becomes involved in the “Zero Hour” program broadcast over Radio Tokyo to U.S. and Allied troops. She is introduced under various names like “Orphan Ann.”

- Early 1944: Toguri becomes aware that U.S. troops have collectively nicknamed female English-speaking propaganda broadcasters “Tokyo Rose.” There is no indication she ever used this name on air.

- April 19, 1945: Iva Toguri marries Felipe D’Aquino, a Portuguese citizen of Japanese-Portuguese ancestry, registered with the Portuguese Consulate in Tokyo. She does not renounce her American citizenship.

- August 1945: Japan surrenders, ending World War II.

- September 1945: U.S. Army authorities arrest Iva Toguri D’Aquino as a security risk. News reports begin to identify her as “Tokyo Rose.”

- October 1945: After an initial investigation by the FBI and the Army’s Counterintelligence Corps, authorities decide that the evidence does not merit prosecution, and Aquino is released from custody in Japan.

- Late 1945: Aquino again requests a U.S. passport.

- Post-1945: American veteran groups and broadcaster Walter Winchell become vocal in their outrage at the possibility of “Tokyo Rose” returning to the U.S., demanding her arrest and trial.

- Subsequent to public furor: The Justice Department re-examines the case and requests the FBI’s investigative records.

- Further investigation: The FBI re-investigates Aquino, interviewing hundreds of former U.S. servicemen, unearthing Japanese documents, and finding recordings of her broadcasts. Many recordings from the initial investigation had been destroyed.

- Continued efforts by the Justice Department: They seek additional evidence, issue a press release asking for soldiers and sailors who heard the broadcasts to contact the FBI, and send an attorney and reporter Harry Brundidge to Japan to find more witnesses.

- September 1948: A grand jury in San Francisco indicts Aquino on several counts, leading to her detention in Japan and transfer to the U.S. under military escort.

- September 25, 1948: Aquino arrives in San Francisco and is immediately arrested by the FBI on a treason charge.

- October 8, 1948: D’Aquino is formally indicted on a charge of treason for aiding the enemy by broadcasting the Japanese “Zero Hour” program.

- July 5, 1949: Aquino’s treason trial begins in San Francisco.

- September 29, 1949: The jury finds D’Aquino guilty on one count of treason, specifically for speaking into a microphone in Tokyo in October 1944 concerning the loss of ships.

- October 6, 1949: Aquino is sentenced to ten years in prison and fined $10,000.

- January 6, 1956: D’Aquino is released from the Federal Reformatory for Women at Alderson, West Virginia, after serving six years and two months.

- October 6, 1959: D’Aquino is fully discharged by expiration of her sentence.

- 1968: An application for pardon is filed on behalf of D’Aquino.

- January 19, 1977: President Gerald Ford grants a pardon to Iva Ikuko Toguri D’Aquino.

- 2006: Iva Ikuko Toguri D’Aquino passes away.

Cast of Characters and Brief Bios

- Iva Ikuko Toguri D’Aquino (aka “Tokyo Rose,” “Orphan Ann”): A Japanese-American woman born in Los Angeles in 1916. She traveled to Japan in 1941 before the outbreak of WWII and remained there. During the war, she worked for Radio Tokyo and participated in the “Zero Hour” propaganda broadcasts aimed at Allied troops. She was later identified as the mythical “Tokyo Rose,” tried for treason, convicted, and eventually pardoned.

- Jun Toguri: Iva Ikuko Toguri D’Aquino’s father. He immigrated to the United States from Japan in 1899 and owned a shop in Chicago where Iva worked after her release from prison.

- Mother of Iva Ikuko Toguri D’Aquino: She immigrated to the United States from Japan in 1913.

- Felipe D’Aquino: A Portuguese citizen of Japanese-Portuguese ancestry whom Iva Toguri married in Tokyo in April 1945. He reportedly warned her to discontinue her role in the “Zero Hour” broadcasts.

- Henry Brundidge: An American reporter who, along with Clark Lee, sought out and interviewed Iva Toguri D’Aquino in post-war Japan, offering her money for exclusive rights and identifying her as “Tokyo Rose.” He was later involved in the efforts to gather evidence against her and reportedly enticed a witness to perjure himself.

- Clark Lee: Another American reporter who collaborated with Henry Brundidge in finding and interviewing Iva Toguri D’Aquino, contributing to the public perception of her as “Tokyo Rose.”

- Walter Winchell: A noted American broadcaster who became outspokenly critical of Iva Toguri D’Aquino and demanded her arrest and trial upon learning of her desire to return to the United States.

- Frank J. Hennessy: The U.S. Attorney in San Francisco who was involved in the treason prosecution of Iva Ikuko Toguri D’Aquino. His correspondence with government officials is mentioned in the court documents.

- Gerald Ford: The President of the United States who granted a pardon to Iva Ikuko Toguri D’Aquino in 1977.

- Thomas Gode: A U.S. Navy Photographer’s Mate 1st Class who filmed Iva Ikuko Toguri D’Aquino in Tokyo in September 1945 while making a CinCPAC newsreel.

Tokyo Rose FBI Files, Court Documents, Audio Recordings & Films

435 pages of files, 1 hour 15 minutes of audio, and 31 minutes of film related to the Iva Ikuko Toguri D’Aquino case, commonly known as “Tokyo Rose.”

D’Aquino was indicted on October 8, 1948, on a charge of treason, the accusation being that she aided the enemy by broadcasting the Japanese “Zero Hour” program over Radio Tokyo to U.S. and Allied troops from November 1943 to August 1945. The jury found D’Aquino guilty on September 29, 1949. She was sentenced to 10 years in prison and a $10,000 fine. D’Aquino was released from the Federal Reformatory for Women at Alderson, WV, on January 6, 1956, and was finally discharged by expiration of sentence October 6, 1959. An application for pardon was filed in 1968 and was granted by President Gerald Ford in 1977.

FBI FILES

313 pages of files copied from FBI Headquarters in Washington, D.C., covering The bureaus’ 1948 espionage investigation of Iva Ikuko Toguri D’Aquino, AKA “Tokyo Rose”. Iva Toguri Aquino, who gained notoriety as the mythical Tokyo Rose, was the seventh person to be convicted of treason in U.S. history.

COURT DOCUMENTS

98 pages of court records relating to the treason prosecution of D’Aquino. They concern legal matters, process of the case through the courts, trial witnesses, other treason investigations and prosecutions, and “Zero Hour” program broadcasts. Includes correspondence of Frank J. Hennessy, the U.S. Attorney in San Francisco, with government officials, primarily officials at the Department of Justice in Washington, DC. Also included is a report on the trial by the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

CLEMENCY FILE

24 pages of correspondence from the Ford Administration clemency file on D’Aquino.

AUDIO RECORDINGS

Zero Hour Broadcast of August 14, 1944 with Iva Toguri D’Aquino as “Ann the Orphan.”

This recording was made by the Federal Communications Commission, Foreign Broadcast Intelligence Service, which operated between 07/28/1942 and 12/30/1945. This sound recording captures a “Zero Hour” Japanese broadcast to Allied forces in the South Pacific. This broadcast contains music; war news and commentary; music with “Ann the Orphan.” The woman in this broadcast is one of a group of women, Iva Toguri D’Aquino, a Japanese-American, who hosted Japanese propaganda broadcast aimed at U.S. forces in the Pacific. The women, both collectively and separately were dubbed “Tokyo Rose” by the American military. The broadcasts included news from the United States, music and commentary.

FILM

Twenty-one minutes of U.S. military films.

Includes a reel of 11 minutes of segments of if Iva Ikuko Toguri D’Aquino filmed by the U.S. Navy. She is filmed talking with Photographer’s Mate 1st Class Thomas Gode and a Japanese policeman outside her Tokyo home during the making of a CinCPAC newsreel on 9 September 1945

A 10-minute reel of an Army Signal Corps film of an re-enactment of a Zero Hour broadcast. (The audio track of this film has heavy cross-talk)

Following the Japanese surrender in September 1945, American forces and news reporters began searching for Japanese military leaders and others who may have committed war crimes. Two of these reporters, Henry Brundidge and Clark Lee, sought “Tokyo Rose,” the notorious siren who tried to demoralize American soldiers and sailors during the war by highlighting their hardships and sacrifices.

Through their legwork and contacts, the two reporters quickly identified one young American woman, Iva Ikuko Toguri d’Aquino, who had made such broadcasts. Brundidge and Lee offered her a significant sum, which they later reneged on paying, for exclusive rights to interview her. Aquino agreed, signing a contract that identified her as Tokyo Rose.

The problem for Aquino, though, was that Tokyo Rose was not an actual person, but the fabricated name given by soldiers to a series of American-speaking women who made propaganda broadcasts under different aliases.

As a result of her interview with the two reporters, Aquino came to be seen by the public, though not by Army and FBI investigators, as the mythical protagonist Tokyo Rose. This popular image defined her in the public mind of the post-war period and continues to color debate about her role in World War II today.

The FBI’s investigation of Mrs. D’Aquino’s activities covered a period of five years. During the course of the investigation, hundreds of former members of the United States Armed Forces who had served in the South Pacific during World War II were interviewed; Japanese documents were unearthed; and recordings of Mrs. D’Aquino’s broadcasts believed to have been destroyed were discovered by the FBI.

Ikuko Toguri was born in Los Angeles on July 4, 1916. Her father, Jun Toguri, had come to the United States from Japan in 1899. Her mother followed in 1913, and the family moved to Los Angeles. During her school years, Ikuko Toguri used the first name of Iva. Toguri enrolled in the University of California at Los Angeles and graduated in 1940. On July 5, 1941, Toguri sailed for Japan from San Pedro, California, without a United States passport. She reportedly gave two reasons for her trip: to visit a sick aunt and to study medicine.

In September of that year, Toguri appeared before the United States Vice Consul in Japan to obtain a United States passport, stating she wished to return to the United States for permanent residence. Inasmuch as she had left the United States without a passport, her application was forwarded to the United States Department of State for consideration. Before arrangements were completed for issuing a passport, the United States was at war with Japan, and no further action was taken by United States authorities with regard to her request.

After the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor, Toguri applied for repatriation to the United States through the Swiss Legation in Japan, but later withdrew the application, indicating she would voluntarily remain in Japan for the duration of the war. Meanwhile, she had enrolled in a Japanese language and culture school. From mid-1942, until late 1943, Toguri worked as a typist for the Domei News Agency; in August 1943, she obtained a second job as a typist for Radio Tokyo.

And later used was used for propaganda broadcasts. Zero Hour was broadcast daily, except Sunday, from 6 p.m. until 7:15 p.m., Tokyo time. Toguri was introduced on the program, which usually began with band music, as “Orphan Ann,” “Orphan Annie,” “Your favorite enemy Ann,” or “Your favorite playmate and enemy, Ann.”

There is no indication that Toguri ever used the nickname Tokyo Rose on the Zero Hour. It was not until early 1944 that she became aware that United States troops had given her that title.

On April 19, 1945, Iva Toguri married Felipe D’Aquino, a Portuguese citizen of Japanese-Portuguese ancestry. The marriage was registered with the Portuguese Consulate in Tokyo; however, Mrs. D’Aquino did not renounce her American citizenship. She continued her Zero Hour broadcast until the cessation of hostilities despite reported warnings by her husband to discontinue her role in the program. After Japan’s surrender in August 1945, United States Army authorities arrested Mrs. D’Aquino as a security risk, and she was kept in various Japanese prisons until her release in 1945.

In September 1945, after the press had reported that Aquino was Tokyo Rose, U.S. Army authorities arrested her. The FBI and the Army’s Counterintelligence Corps conducted an extensive investigation to determine whether Aquino had committed crimes against the U.S. By the following October, authorities decided that the evidence then known did not merit prosecution, and she was released.

Before the year was out, Aquino again requested a U.S. passport. American veteran groups and noted broadcaster Walter Winchell learned of this and became outraged that the woman they thought of as “Tokyo Rose” wanted to return to this country. They demanded that the woman they considered a traitor be arrested and tried, not welcomed back.

The public furor convinced the Justice Department that the matter should be re-examined, and the FBI was asked to turn over its investigative records on the matter. The FBI’s investigation of Aquino’s activities had covered a period of some five years. During the course of that investigation, the FBI had interviewed hundreds of former members of the U.S. Armed Forces who had served in the South Pacific during World War II, unearthed forgotten Japanese documents, and turned up recordings of Aquino’s broadcasts. Many of these recordings, though, were destroyed following the initial decision not to prosecute Aquino in 1946.

The Department of Justice initiated further efforts to acquire additional evidence that might be sufficient to convict Aquino. It issued a press release asking all U.S. soldiers and sailors who had heard the Radio Tokyo propaganda broadcasts and who could identify the voice of the broadcaster to contact the FBI. Justice also sent one of its attorneys and reporter Harry Brundidge to Japan to search for other witnesses. Problematically, Brundidge enticed a former contact of his to perjure himself in the matter.

With new witnesses and evidence, the U.S. Attorney in San Francisco convened a grand jury, and Aquino was indicted on a number of counts in September 1948. She was detained in Japan and brought under military escort to the U.S., arriving in San Francisco on September 25, 1948. There, she was immediately arrested by FBI agents, who had a warrant charging her with the crime of treason for adhering to, and giving aid and comfort to, the Imperial Government of Japan during World War II.

Aquino’s trial began on July 5, 1949, one day after her 33rd birthday. On September 29, 1949, the jury found her guilty on one count in the indictment. The jury ruled that:

“…on a day during October 1944, the exact date being to the Grand Jurors unknown, said defendant, at Tokyo, Japan, in a broadcasting studio of the Broadcasting Corporation of Japan, did speak into a microphone concerning the loss of ships.” On October 6, 1949, Aquino was sentenced to ten years of imprisonment and fined $10,000 for the crime of treason.

On January 28, 1956, she was released from the Federal Reformatory for Women at Alderson, West Virginia, where she had served six years and two months of her sentence. She successfully fought government efforts to deport her and returned to Chicago, where she worked in her father’s shop until his death. President Gerald Ford pardoned her on January 19, 1977. She passed away in 2006.

Related products

-

Tulsa Oklahoma African American Newspaper Tulsa Star 1913-1921

$9.90 Add to Cart -

Watergate: Congressional hearings, reports, exhibits, and transcripts

$19.50 Add to Cart -

The Revolution Susan B Anthony Suffrage/Women’s Rights

$19.50 Add to Cart -

African American Slave Testimonies and Photographs

$19.50 Add to Cart